Disclaimer: Psychedelics are largely illegal substances, and we do not encourage or condone their use where it is against the law. However, we accept that illicit drug use occurs and believe that offering responsible harm reduction information is imperative to keeping people safe. For that reason, this document is designed to enhance the safety of those who decide to use these substances.

This article has been medically reviewed by Katrina Oliveros, MSN-ED, BSN

Maria Katrina is a trauma-informed Wellness Educator and Psychedelic Harm Reduction Consultant. Beyond nursing, she supports health & wellness teams through medical aid, psychedelic harm reduction, and integration services.

What is the science behind psychedelic visuals? Why do people experience common visual effects with psychoactive substances? And why do people have visuals at all when they embark on psychedelic journeys?

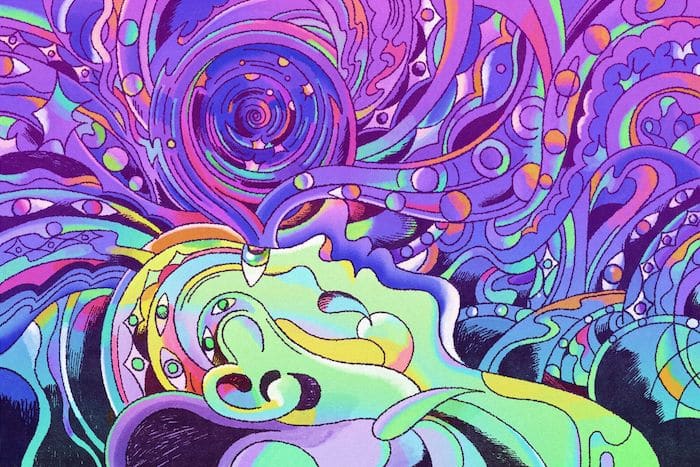

When you journey with psychedelics, you can experience a range of visual effects. These effects can be mild or fully immersive. They can include a stunning display of colors, geometry, symbols, images, scenes, and even storylines. Many psychedelic visuals seem to be shared across space and time.

This article will explain the science of psychedelic visuals, the types of psychedelic visuals (e.g., closed-eye vs. open-eye visuals), and how different psychedelic drugs provide a spectrum of visual experiences.

What Are Psychedelic Visuals?

Visual effects are often one of the most prominent features of a psychedelic experience. When you hear the word “psychedelic,” your mind might associate it with colorful and intricate patterns.

There is a huge range of visual effects that you might experience with the use of psychedelics, but they fall generally under four categories: enhancements, distortions, geometry, and hallucinations.

The Science of Psychedelic Visuals

There is a lot going on in the human brain when psychedelic visuals occur.

Activity at the 5-HT2A Receptors

The effects of classic psychedelics, including visual effects, are mediated by their action at serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. They act as agonists at these receptors, which means they bind to them and cause them to produce a biological response, thus mimicking the role of the endogenous neurotransmitter–serotonin in this case.

We know this activity is responsible for psychedelic visual effects because the administration of the drug ketanserin (which is a 5-HT2A antagonist) both before and during a psychedelic experience blocks psychedelic effects, including perceptual distortions and hallucinations. (In chemistry and medicine, an antagonist is a substance that stops the action or effect of another substance. Since ketanserin is a 5-HT2A antagonist, it prevents classic psychedelic molecules from activating the 5-HT2A receptors.) Multiple studies have produced these results.

Geometric Visual Effects Relate to the Architecture of the Brain

In a 2002 paper, a group of researchers refer to the work of German psychologist Heinrich Klüver, who organized geometric visual hallucinations into four groups, called form constants:

- Tunnels and funnels

- Spirals

- Lattices, including honeycombs and triangles

- Cobwebs

In most cases, geometric psychedelic visuals are seen with both eyes and move with the eyes. The researchers in the 2002 paper interpret this as meaning that psychedelic visuals are generated in the brain. They theorize that hallucinations originate in the primary visual cortex (area V1), the area of the cerebral cortex that is essential to the processing of visual stimuli. The architecture of V1, in other words, determines the geometric effects you see during a psychedelic journey.

These researchers modeled the primary visual cortex as a lattice of interconnected hypercolumns or blocks that contain “all the machinery necessary to look after everything the visual cortex is responsible for, in a certain small part of the visual world” (Hubel, 1982).

Each of these hypercolumns is comprised of a number of interconnected columns that correspond to different orientations. These orientation columns display what is known as a shift-twist symmetry, while the hypercolumns display a lattice symmetry. The researchers use this symmetry to show how form constants can emerge when V1 is stimulated, such as by psychedelics. They also note that “the cortical mechanisms which generate geometric visual hallucinations are closely related to those used to process edges, contours, textures and surfaces.”

The neurobiologist Jack Cowan, who was involved in the 2002 study and is an expert on geometric visual hallucinations, previously suggested in a 1982 paper that activity moving across the visual cortex could be responsible for the experience of seeing or moving through a tunnel. This is due to the way that the retina maps onto the surface of the visual cortex.

The architecture of the brain is also fractal by nature, meaning that the same patterns repeat at different scales. This could help to explain why people often report fractal visuals when working with psychedelics.

As renowned psychedelic researcher Robin Carhart-Harris states in reference to psychedelic visuals:

Like tree branches, the brain recapitulates [itself]. You are not seeing the cells themselves, but the way they’re organized – as if the brain is revealing itself to itself.

Perceiving or traveling through different dimensions, meanwhile, might be the outcome of geometric hallucinations varying in the three dimensions of space and in time.

The Science of Psychedelic Visuals: Hierarchical Ordering of Brain Networks

The “relaxed beliefs under psychedelics” (REBUS) model, proposed by Carhart-Harris and Karl Friston, focuses on the notion of brain networks being ordered in a hierarchy. Networks like the default mode network (DMN) and central executive network (CEN) are higher-level networks, while areas like the hippocampus and visual cortex are seen as lower-level.

According to the REBUS model, this hierarchical ordering collapses under the influence of psychedelics. Higher-level networks like the DMN and CEN lose control over the lower-level regions. This loss of control allows the lower-level regions to act in an unconstrained way, which can result in many visual effects that you may experience when journeying with psychedelics.

Normally, lower-level regions like the visual cortex make predictions about our sensory input, and these are compared with our actual sensory input to see if those predictions are correct. This comparison helps our brains to construct an accurate model of the world, which is of course evolutionarily advantageous.

However, prediction errors can occur, which are the differences between predicted and actual sensory input. When these prediction errors originate from lower-level systems, the higher-level systems ordinarily update them since they have that top-down control.

But under the influence of psychedelics, the higher-level regions lose that control. This means that prediction errors from lower-level regions can, as Carhart-Harris and Friston state, “find freer register in conscious experience, by reaching and impressing on higher levels of the hierarchy.”

They add that “this straightforward model can account for the full breadth of subjective phenomena associated with the psychedelic experience,” including “entity encounters,” “eyes-closed dreamlike visions,” and “geometric hallucinations”.

According to the REBUS model, [the brain’s] hierarchical ordering collapses under the influence of psychedelics. Higher-level networks like the DMN and CEN lose control over the lower-level regions. This loss of control allows the lower-level regions to act in an unconstrained way, which can result in many visual effects that you may experience when journeying with psychedelics.

The Role of the Thalamus in the Science of Psychedelic Visuals

Another theory – the thalamic filter model – suggests that the main effects of psychedelics are related to the function of the thalamus and its relation to other areas in the brain. This theory is also known as thalamic gating or cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical gating (CSTC).

The thalamus is like a relay station for pretty much all sensory information (excluding smell). Normally, the thalamus restricts certain information from entering the rest of the brain, such as the visual cortex.

However, according to the CSTC or thalamic gating theory, psychedelics prevent this inhibition of information flowing from the thalamus to other brain regions. The result is that we experience sensory data in a raw and unprocessed way.

Dreaming While Awake

A 2019 study published in Scientific Reports found that DMT creates an experience that is like “dreaming while awake,” in the words of Carhart-Harris. This study, led by Christopher Timmermann, was based on the use of an electroencephalogram (EEG) to measure brain waves (synchronized electrical pulses from masses of neurons).

Under the influence of DMT, participants experienced a reduction in alpha waves (which the brain produces while we’re awake). This was observed alongside increases in delta and theta waves, which are associated with dreaming.

As in the dream state, people on DMT are cut off from external reality while being immersed in what feels like another world. In a Newsweek article, Timmermann said:

“We saw an emergent rhythm that was present during the most intense part of the experience, suggesting an emerging order amidst the otherwise chaotic patterns of brain activity. From the altered brainwaves and participants’ reports, it’s clear these people are completely immersed in their experience—it’s like daydreaming only far more vivid and immersive, it’s like dreaming but with your eyes open.”

Entities and the Evolved Brain

The brain is an evolved organ. It is primed to detect certain things in the environment, endowing us with innate psychological tendencies.

The anthropologist Michael Winkelman wrote a 2018 paper that examined entities seen in psychedelic states from this evolutionary perspective. He discovered that ayahuasca and DMT entities were similar in nature to our ideas of gnomes, dwarves, elves, angels, and aliens. He believes that psychedelic entities “exemplify the properties of anthropomorphism, exhibiting qualities of humans.”

Winkelman argues that the various features of psychedelic entities reflect aspects of our brain function that evolved to our advantage.

These innate faculties include:

- Agency detection: We are biologically programmed to detect predators, prey, and allies, even in objects and events where they do not exist or are unlikely to exist.

- Anthropomorphism: The tendency to attribute human characteristics to non-human animals, natural features, or events.

- Theory of Mind (ToM) or mind reading: Inferring the mental states – such as intentions, thoughts, and desires – of others. This helps us to explain and predict their behavior.

If psychedelics like DMT activate these faculties, then this might help account for the human-like appearances and behaviors of psychedelic entities. The brain also tries to detect patterns in ambiguous stimuli. As we will see in the next section, face pareidolia – recognizing faces in random patterns – is another type of psychedelic effect, and it’s a tendency that offers us an evolutionary advantage.

If psychedelics activate this tendency, along with the others noted by Winkelman, then this could help explain the entities that many people encounter. The added effect of geometry might also help explain some of these entities’ strange or complex features.

Grow 1 Year's Worth of Microdoses in Just 6 Weeks

Third Wave partnered with top mycologists to create the world’s easiest and best mushroom growing program (kit, course, and expert support).

- Pre-sterilized and sealed

(ready to use out of the box) - Step-by-step video and text course

- Access to growing expert in community

- Make your first harvest in 4-6 weeks

- Average yield is 1 - 4 ounces (28-108g)

- Fits in a drawer or closet

- Enter info for Third Wave discounts:

Grow 1 Year's Worth of Microdoses in Just 6 Weeks

Third Wave partnered with top mycologists to create the world’s easiest and best mushroom growing program (kit, course, and expert support).

- Pre-sterilized and sealed

(ready to use out of the box) - Step-by-step video and text course

- Access to experts in community

- Make your first harvest in 4-6 weeks

- Average yield is 1 - 4 ounces (28-108g)

- Fits in a drawer or closet

- Enter info for Third Wave discounts

4 Main Psychedelic Visual Effects

1. Enhancements

- Color enhancement: Intensification of how vivid or bright colors appear.

- Visual acuity enhancement: The enhancement of how clear your vision is. Visual details in your external environment become sharpened and well-defined.

- Magnification: Also known as macropsia or megalopsia, magnification occurs when objects appear larger than their true size.

- Pattern recognition enhancement: Also known as pareidolia, pattern recognition enhancement involves a heightened ability to detect often meaningful images in ambiguous stimuli (e.g., seeing faces in different objects, which is specifically known as face pareidolia).

2. Distortions

- After-images: Seeing something in your field of vision even after the original object is no longer there. For example, moving objects may produce a trail of still images behind them. Another type of after-image is seeing a residual image of what you can see with eyes open when you close your eyes, which gradually fades. The after-image effect is also known as palinopsia.

- Tracers: Tracers are similar to after-images, but they differ in that trails are left behind moving objects, rather than images. The effect is reminiscent of long-exposure photography.

- Drifting: Seeing the textures and shapes of objects warp, melt, flow, morph, and “breathe.”

- Color replacement: When your whole visual field or particular objects have their original color replaced with an alternative one.

- Color shifting: Colors fluidly shift in a repeating cycle, such as from red to blue to green and back again.

- Diffraction: Seeing spectrums of color when looking at the brighter sections of your visual field.

- Perspective distortions: Objects appear larger, smaller, nearer, or farther away than normal.

- Recursion: The repetition of certain sections of your external environment, producing fractal-like patterns, which can have the feeling of being zoomed into or out of infinity.

Grow 1 Year's Worth of Microdoses in Just 6 Weeks

Third Wave partnered with top mycologists to create the world’s easiest and best mushroom growing program (kit, course, and expert support).

- Pre-sterilized and sealed

(ready to use out of the box) - Step-by-step video and text course

- Access to growing expert in community

- Make your first harvest in 4-6 weeks

- Average yield is 1 - 4 ounces (28-108g)

- Fits in a drawer or closet

- Enter info for Third Wave discounts:

Grow 1 Year's Worth of Microdoses in Just 6 Weeks

Third Wave partnered with top mycologists to create the world’s easiest and best mushroom growing program (kit, course, and expert support).

- Pre-sterilized and sealed

(ready to use out of the box) - Step-by-step video and text course

- Access to experts in community

- Make your first harvest in 4-6 weeks

- Average yield is 1 - 4 ounces (28-108g)

- Fits in a drawer or closet

- Enter info for Third Wave discounts

3. Geometry

When working with psychedelics, it is common to see geometric patterns and fractals partially or completely covering your field of vision.

These patterns can be fast-moving, brilliantly colorful, and ineffably complex. Geometric psychedelic visuals can vary in intensity and complexity. The geometry of psychedelic states can also manifest in many different styles.

Users describe geometric psychedelic visuals ranging from:

- Intricate to simple

- Organic to synthetic

- Multicolored to monotone

- Sharp to soft

- Fast to slow-moving

- Smooth to jittery

- Round to angular

- Non-immersive to immersive

4. Hallucinations

- Transformations: Seeing objects in your environment undergo a process of metamorphosis, changing from one form into another, often in a fluid manner.

- External hallucinations: Visual hallucinations with your eyes open that manifest in the external environment, which may be vague or well-defined images. External hallucinations can include entities, objects, scenarios, plots, scenery, and people that don’t exist in reality.

- Internal hallucinations: Similar to external hallucinations, except internal hallucinations occur when your eyes are closed.

The intensity of psychedelic visuals often varies depending on dosage. But they can increase as well through drug combinations and factors related to your set and setting.

Open-Eye Visuals vs. Closed-Eye Visuals

Open-eye visuals (OEVs) are changes to how you perceive things in your external environment. On a low-medium dose of a psychedelic, your environment or the objects in it can warp.

This warping means that objects might bend or ripple as if made of liquid, or the objects can be seen to melt or “breathe” (steadily contract inwards and expand outwards). If you take higher doses, you can experience external hallucinations.

Closed-eye visuals (CEVs) are the patterns and images you see when you close your eyes during a psychedelic experience.

Depending on the substance, dose, and set and setting, CEVs can range from being indistinct to as clear as anything you see in sober reality.

Substances That Cause Psychedelic Visuals

There are many different types of substances that can produce psychedelic visual effects, including:

Classic Psychedelics

Non-Classic Psychedelics

Novel Psychedelics

Do Psychedelic Visuals Vary Depending on the Psychedelic?

Many people find specific psychedelics are associated with unique psychedelic visuals.

For instance, some describe magic mushroom visuals as soft, rounded, and organic, in contrast to LSD visuals, which may be described as sharper, more angular, and more electric.

However, a study published last year in the journal Neuropsychopharmacology examining the effects of different doses of LSD and psilocybin found few differences between the two psychedelics. This 2022 study on healthy volunteers, led by Matthias Liechti from the University of Basel, concluded:

“Both doses of LSD and the high dose of psilocybin produced qualitatively and quantitatively very similar subjective effects, indicating that alterations of mind that are induced by LSD and psilocybin do not differ beyond the effect duration. Any differences between LSD and psilocybin are dose-dependent rather than substance-dependent. However, LSD and psilocybin differentially increased heart rate and blood pressure.”

Anecdotally, reports of differences between LSD and psilocybin experiences show that many people find LSD visuals are comparable to its cognitive effects: sharper and clearer than psilocybin. With LSD, it also seems to be more common to experience tracers and objects “breathing.”

In contrast, psilocybin mushrooms can produce visual effects that are more “flowy” like water, with colors more heavily affected and objects more likely to transform. It’s important to bear in mind, however, that our assumptions about different psychedelics are part of our set (or mindset) and may, therefore, influence our psychedelic experiences.

In contrast to many anecdotal reports, the authors of the 2022 study reported effective blinding. This meant that very few participants were able to correctly identify which drug they had taken, except when they received a placebo.

Despite the psychedelic research on LSD and magic mushrooms, chemical differences between different types of psychedelic drugs may still translate into varying visual effects.

For instance, encountering autonomous entities is considered a hallmark effect of the DMT experience. Meeting entities can also occur during journeys with mushrooms and LSD, but it is not typically as regular an occurrence as with DMT. Why this should be the case is still a mystery.

Final Thoughts on the Science of Psychedelic Visuals

There’s still a lot we don’t know in terms of the science of psychedelic visuals. There is no single theory that can explain the myriad ways in which psychedelics affect visual perception.

However, the science of psychedelics is helping to shed light on many aspects of the psychedelic experience that we used to be completely in the dark about. Yet understanding the origin of psychedelic visuals in the brain does not reduce their meaning.

This may allow us to realize that our visions connect us to our long history as evolved creatures. These effects of psychedelics also become a source of creative inspiration for many artists.

It’s also important to understand that psychedelic visuals, while aesthetically impressive, do not seem to be critical in terms of therapeutic effects. Instead, factors like psychological insight (even more so than mystical effects) are strong predictors of subjective well-being.

Getting the most from psychedelics also depends on effective integration: how you make sense of your experiences and decide to apply them to the various aspects of your life.

To find out more about how you can benefit from psychedelics, you can check out the Third Wave Directory, which includes listings of vetted therapists, psychedelic retreats, and psychedelic clinics.

Third Wave’s Mushroom Grow Kit can also enable you to have a reliable source of psychedelics.

Grow 1 Year's Worth of Microdoses in Just 6 Weeks

Third Wave partnered with top mycologists to create the world’s easiest and best mushroom growing program (kit, course, and expert support).

- Pre-sterilized and sealed

(ready to use out of the box) - Step-by-step video and text course

- Access to growing expert in community

- Make your first harvest in 4-6 weeks

- Average yield is 1 - 4 ounces (28-108g)

- Fits in a drawer or closet

- Enter info for Third Wave discounts:

Grow 1 Year's Worth of Microdoses in Just 6 Weeks

Third Wave partnered with top mycologists to create the world’s easiest and best mushroom growing program (kit, course, and expert support).

- Pre-sterilized and sealed

(ready to use out of the box) - Step-by-step video and text course

- Access to experts in community

- Make your first harvest in 4-6 weeks

- Average yield is 1 - 4 ounces (28-108g)

- Fits in a drawer or closet

- Enter info for Third Wave discounts

I experience every other aspect of the lsd except visual ; while my friend are seeing a lot of visual ! i even tested higher doses and the result is the same… no visual !

It would be nice to consider different perspectives aside from the scientific approach. There’s lot’s of information on how this is perceived by indigenous peoples for example. Often, out of heritage and experience, they have a lot of knowledge about the significance of visionary experiences. Including these perspectives in todays often rational ”trying to understand Psychedelics” journey could be very beneficial. That in order for us to have a much more informed understanding of these mystical concepts.

I agree Roel, The “science” mentioned in the article feels mechanistic and very limiting toward the goal of seeing and knowing what might be a truer, albiet largely invisible, reality. Actually, I think we live in a projected hologram- in this sense, the brain, as they said, “generates” the visuals, but in the same way it “generates” what we see as a physical, “normal” world around us…