“Once upon a time in a galaxy far, far away… “

I can almost guarantee you that with those words a story flashed in your mind (and most probably, an unmistakable orchestral melody). A story that is entirely fictional, but not untrue.

Most of us see ourselves as the protagonists in our own story, but most of us will also agree that we are our own antagonists as well. Stories are how we define ourselves, how we document and make sense of what has happened, what is happening, and what is to come.

Stories are a way of placing ourselves within a greater context, and giving meaning to the time we spend alive on this planet. The experience is universal. Stories are tools of understanding, methods of expanding consciousness, of living other realities. Stories give us hope, answers, lessons – they excite us, delight us, terrify us, and challenge us.

The very same can be said of psychedelics.

Psychedelic Stories

Stories, like psychedelics, can detach us from situations so that we can deal with them. Not only that; but just as a metaphor is a way of explaining something in another context using symbols, so too do stories and psychedelics give our minds a relative simulation from which to learn.

We can keep things at a distance, knowing that they are not real – but this is of course also where psychedelics can become dangerous – in the blurring between fantasy and reality.

This is where Frodo, Homer Simpson, and Tyler Durden come in. We know their worlds are not real, so we can project ourselves there within the safety of our own imaginations.

I’m not talking specifically about how psychedelics or any mind-altering substances inspired or fuelled creative works. That much is obvious. I’m arguing that both mind-altering substances (specifically psychedelics) and stories serve the same function – as a problem-solving tool for our species. A tool carved from the same source as meditation, mindfulness, discipline, and therapy. Hearing, experiencing, and telling a story is a great way to have fun. So are psychedelics. But hearing, experiencing, and telling stories is also a tool, and so too are psychedelics.

The Power of the Story

Stories are a symbolic rite of passage that act as a road-map for when one must truly face the wilderness, or enter the cave, or slay the beast. Famed anthropologist, theologian, and author Joseph Campbell said, “The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

The cave that Campbell, and many others such as Jung and Freud, are talking about, is a journey into our subconscious. In both the mind and in narratives, this cave can be an actual cave, or a metaphorical one. It’s facing a fear, and returning victorious having learned something new about ourselves or the world around us.

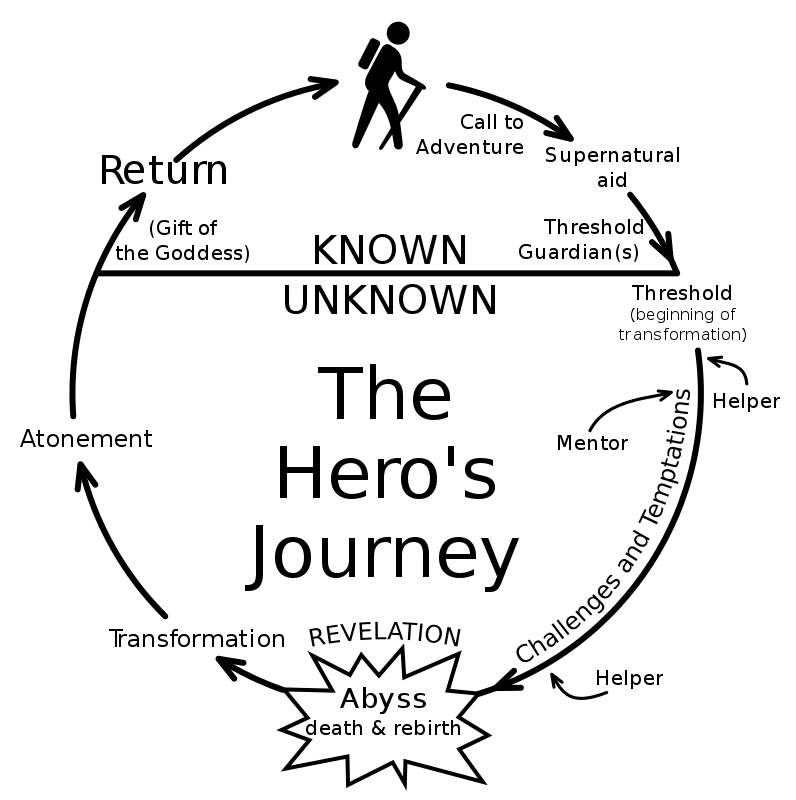

Joseph Campbell is famous for his archetypal story structure device, “The Hero’s Journey,” from his book The Hero With A Thousand Faces, which he derived after studying hundreds of myths, legends, and religious texts. His book and discoveries cover much more than a simple story structure, but this is what has grabbed the public’s attention.

If you know the storyline of the original Star Wars films, then you have the gist of this narrative structure. Even if you’ve never seen the films, and unless you have a very strict no pop-culture filter, you must have heard of Luke Skywalker, Yoda, and Darth Vader.

I now know why seeing those pictures as a child excited my heart and mind so much, and why Star Wars itself has become a worldwide cultural phenomenon. Stories like it have gained popularity on a religious scale. This structure is so common, it is even used with archetypal work in psychotherapy, mostly by Jungian analysts, as a way of exploring, explaining, and guiding patients’ psychological journeys.

Just as Luke Skywalker goes into the swamps of Dagobah, or Campbell’s Hero enters the cave, the mind of someone under the spell of the natural psychedelic DMT also goes into paths untread and waters unknown…

Entering the Cave with DMT

The uncanny thing about DMT is not only that it is naturally occurring in both humans and plants, but that the similarities in users’ experiences are strikingly archetypal, narrative, and transcendental. Since its documentation in the 1950s, terms like “machine elves” and “higher beings” have been a common theme in DMT trips. Taking DMT can be described as being plunged into a world consisting entirely of metaphors – a world that questions everything and yet cannot adequately be conveyed.

One of the most common ways DMT is ingested is in the form of ayahuasca, which has been drunk by Amazonian shamans for thousands of years. Today facilities and services offering ayahuasca ceremonies as a spiritual and psychological catharsis have sprung up globally. Many have used it to break addictions to substances such as heroin, or simply reconcile themselves with past trauma.

A person who has been visited by the sage-elves of a DMT trip will recount their experience with the same fervor as a kid who just saw the latest Marvel film, or gush forth like an aspiring author who has been energized by a book, or probably most acutely, as someone who has caught a glimpse of god.

What does god have to do with it?

The history of stories is also the history of religion. Across cultures, continents, and centuries the stories of our ancestors and gods were chosen as the most important. For the three Abrahamic religions – Christianity, Islam, and Judaism – their written gospel is divine doctrine. It’s the very thing that glues their organizational faith together.

Listen to Jerry Brown discuss Christianity’s history with drugs, or Biblical scholar Danny Nemu expose the appearance of drugs in the bible, on The Third Wave Podcast.

The earliest known author is mentioned in ancient Sumerian texts as Enheduanna, King Sargon Akkad’s daughter who lived during the 24th Century BC. She is known for her writings and hymns dedicated to the goddess Inanna. The Epic of Gilgamesh, from where the biblical flood myth stems, is dated to 2100-1800 BC. It chronicles the quests of King Gilgamesh and his interactions with the gods, and it practically reads like a Sumerian Superman story arc. In Hinduism, the Rig Veda is estimated to have been composed between 1700-1100 BCE, and is still used in rites of passage to this day. The Bible has been printed more than five billion times (almost as many dollars as The Passion of The Christ made).

It’s quite the popular story anthology. Religious history, in its documented state, can be seen as but a custom and collection of stories, myths, and lessons from the past re-told for future generations.

One could argue that this Campbellian worldview of the Hero as the center of the narrative’s universe is admittedly somewhat of a Westernized, individualized, and simplified version of an archetypal story; but actually, this myth it’s more of a guideline than a rule. It’s not necessarily a proclamation of humanity’s lived experience, for there are many other ancient tales that teach. It’s one attempt at a grand unified theory for stories.

The Story Cycle

The Hero’s Journey is a circle, or a “story cycle” with a beginning and an end. But being a circle, it is also infinite and repetitive. As the story or character progresses clockwise along the circle, it passes through key points and events, eventually concluding where it began. In its most granular and simplest form, the structure follows the premise of entering an unfamiliar world, going into unchartered territory, seeking answers to questions, and paying a price for it. What makes psychedelics so appealing is that the price is rarely heavy… if used responsibly and with respect.

This cycle, story, or journey can be something as simple as the tale of a man needing to buy milk, or as complex and twisting as someone taking LSD. Dan Harmon, creator of the popular TV series Rick and Morty, said it best: “Get used to the idea that stories follow that pattern of descent and return, diving and emerging. Demystify it. See it everywhere. Realize that it’s hardwired into your nervous system, and trust that in a vacuum, raised by wolves, your stories would follow this pattern.”

This pattern, not unlike a key, is where the Venn diagram of psychedelics, stories, and consciousness intersect. It’s not news that this loop is found everywhere – in life cycles, seasons, orbits, stars being born, your lunch-hour, myths, clocks. It is the eternal concept of ouroboros – the hero goes on journey after journey, failing at his tasks and overcoming the odds in equal measures.

Now let’s say instead of this story structure to aid in a journey of change, you have a group of molecules called “psilocybin,” “mescaline,” or “LSD.” Just like stories have genres, so do psychedelics. Tryptamines, lysergamides, phenethylamines; each with its own character, style, and color. Art imitates life in this aspect, as each genre has its own structure and is crafted to elicit a certain emotional response. So too, do these different types of chemicals affect our brains.

Once these substances enter your body, you become the protagonist going down the rabbit hole; you pass into the subconscious, into an unknown world, and you dwell there until the drug wears off. Then you return to society with (hopefully) a new experience unique to that trip. The drug becomes the archetypal Mentor (the word “mentor” originates from Homer’s Odyssey), as in the monomyth. It’s the role of Merlin, Gandalf, The Fairy Godmother, or Yoda – in psychoactive form.

But of course, owing to many factors, the substance can also become one of the other archetypal forms – the trickster, ally, shapeshifter, shadow, herald, or guardian. When under the influence, it really is a matter of perspective – perspective that one can only fully comprehend once the experience has come full circle, just like a story. You will find its worth by telling it in its entirety.

Stories of Healing

Dan Harmon wrote that, “whereas the health of an individual depends on the ego’s regular descent and return to and from the unconscious, a society’s longevity depends on actual people journeying into the unknown and returning with ideas.”

In the context of the Hero’s Journey or the narrative circle, these people are the heroes of everyday life. Doctors, engineers, scientists, artists, authors, politicians, freethinkers – all have ideas that run and shape the world. Stories drive empathy, which grows society, because we relate to the narrative. It’s partly why we have such vivid imaginations. When an idea is told with a great story, great things can happen.

The descent and return that Dan Harmon speaks of is indeed required for those who go through psychotherapy. When this is coupled with psychedelics in a controlled environment, the results can be impressive. There is a building wealth of knowledge available that demonstrates this, especially amongst sufferers of PTSD or depression. Under the guidance of practitioners and a medically administered dose of LSD, psilocybin, or MDMA, they are able to return to that cave and gradually overcome the fear that holds them back.

The efficacy of psychedelic therapy does not mean it is literally a magic pill. Studies like these aim to show that the substances make the process manageable as part of a holistic program. While the positive effects vastly outweigh the negative side-effects, it is not for everyone.

One practical and safe approach exists in the form of microdosing. If you take stories, mindfulness, and psychedelics as interchangeable metaphors, microdosing is like reading an inspiring passage each day. One intense, guided, and powerful hit of psychedelics is a rocket trip to outer space, but with microdosing you have a throttle.

The practice itself is unchartered territory too, but the very fact that you’re reading this article on this website means the momentum is growing. With the growing knowledge of it as a tool, comes the growing need to have guidance, to have stories we can tell of its success. Here we have a tool, which we have used for as long as we have been around, but are only now beginning to understand.

Listen to our podcast with Erick Godsey if you want to find out What Is The Mystical Cure for Depression or Click here to read the transcript

The Great Cycle

I propose that the great cycle that permeates all these processes is not purely symbolic, coincidental, or separate. Rather, it’s an integral part of life. I believe that shying away from these ancient teachers is not progress, but regress. Surely if something is this prevalent, we should pay attention to it?

Although not the only path, psychedelics are one avenue to explore our capabilities. In a world driven by the rush to acquire more resources, here is one source we have woefully neglected. We owe it to our ancestors and our children to take their advice – to build on old ideas with new knowledge. As Terence McKenna, American ethnobotanist, mystic, psychonaut, lecturer, author, and psychedelic advocate, so famously said:

“You are an explorer, and you represent our species, and the greatest good you can do is to bring back a new idea, because our world is endangered by the absence of good ideas. Our world is in crisis because of the absence of consciousness.”

Ideas are constantly thrown at us via the news, films, books, social media, and television. But these are seldom our own ideas. All too often, these ideas are blurred through the lens of a capitalist agenda and seen as re-hashed and pre-programmed, ideas that obfuscate the truth and end up existing purely for consumption instead of contemplation.

The problem with most television, popular culture, and the search for honesty is that there is so much noise. That noise is projected at us because our consumption of it drives up profit. Notions that might propel us are made taboo because they don’t fit in with a society that values progress at the cost of life, versus progress for life.

McKenna again bluntly said we should “stop consuming images and start producing them.” Let’s produce ones that propel us toward becoming better. The news media, pop culture, humankind’s history, and your own personal journey are all presented to and decoded by us as a narrative – one in which we have the individual power to rewrite and reroute.

We must decide for ourselves which tools we want to use to shape a better storyline. They have been around a lot longer than we have.

Words by George van der Riet

A personal story. Once jupon a time I was in High school. I did what kids during that time did.

I was fourteen and cut school with a few friends to set about building a tree house.

I had no idea what lay before me that night. From the Allman Brothers to Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. I met a thick brick, walked down a yellow brick road. Found my way to

a white room with no curtains. I awoke to “Good Morning, Good Morning”, I had never thought someone could find their way into that other world I never knew existed.

If only we could all find ourselves with a completely new outlook on how our world really exists.

I love this phrase: microdosing is like reading an inspiring passage each day.