The Ultimate Guide to

Peyote

(Mescaline, Mescalito, Anhalonium, Buttons)

Peyote is an endangered species and care should be taken to avoid purchasing specimens that have been illegally poached from the wild. Mescaline, the primary psychoactive alkaloid, is also an illegal substance in many countries, and we do not encourage or condone the use of this it where it is against the law. However, we accept that illegal drug use occurs, and believe that offering responsible harm reduction information is imperative to keeping people safe. For that reason, this guide is designed to ensure the safety of those who decide to use peyote responsibly.

Overview

01Native to Mexico and the Southwestern US, peyote has long been a focus of Native American and pre-Colombian ceremonial traditions. Its name derives from the Nahuatl (Aztec) term peyotl and it remains legal for ceremonial use in the US under the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. Today, it’s also used in other contexts elsewhere, including in meditation and psychotherapy. It also holds the reputation of being the first psychedelic to come to mainstream Western attention—for better or worse. Due to overharvesting and peyote’s slow-growing nature, the cactus is now an endangered species.

In ceremonial use, peyote is typically either chewed to release the active alkaloids or brewed as a tea. The peyote trip is characterized by visual effects (such as enhanced colors and breathing environments), philosophical and introspective insights, and feelings of euphoria.

Beyond LSD and Psilocybin is a field. This guide will take you there.

In Third Wave’s Ultimate Guide to Safely Sourcing Psychedelics, you will discover an astonishing menu of psychedelic medicines…

…and how to source them without legal risk.

Beyond LSD and Psilocybin is a field. This guide will take you there.

In Third Wave’s Ultimate Guide to Safely Sourcing Psychedelics, you will discover an astonishing menu of psychedelic medicines…

…and how to source them without legal risk.

Experience

02What to expect

The effects of peyote are usually felt within 30 minutes to an hour after consumption. For most, the experience begins with increases heart rate, blood pressure, and body temperature and some form of physiological discomfort, such as nausea, fullness in the stomach, sweating, and/or chills. These physical symptoms can last up to two hours, before dissolving into a sense of calm and acceptance.[1]

At this point, the more subjective, psychological effects take hold, reaching their peak two to four hours after consuming the cactus and gradually declining over the next eight to twelve hours. Peak effects are compared to those of LSD, and are known to profoundly alter one’s perceptions of self and reality, increase suggestibility, and intensify emotions. While some find peyote more sensual and less reality-shifting than LSD, others have trouble telling the difference.

Some people experience a deeply mystical or transcendental state, including clear and connected thought, feelings of oneness and unity, self-realization, and ego death, as well as empathy and euphoria. “Bad trips” and dysphoric symptoms tend to be more common among people who ignore the importance of set and setting and/or have a history of mental illness.

Visual effects are also common, including color enhancement, visual distortions (such as “melting” or “breathing” environments), geometric patterns, and the appearance of seemingly autonomous entities.[2] A number of users, including the writer Robert Anton Wilson in his autobiographical book Cosmic Trigger, describe encounters with a little green man, or the “spirit of the plant,” who is often called “Mescalito.”[3][4]

Effects

03Pharmacology

Something of a “little green chemical factory,” peyote contains more than 60 different alkaloids, many of which are at least potentially psychoactive to varying degrees, including tyramine, hordenine, pellotine, and anhalonidine.[5] But the primary psychoactive alkaloid is mescaline.[6]

Receptor binding

Mescaline binds to virtually all serotonin receptors in the brain but has a stronger affinity for the 1A and 2A/B/C receptors. It’s structurally similar to LSD and often used as a benchmark when comparing psychedelics.

Like nearly all psychedelics, the effects of mescaline are likely due to its action on serotonin 2A receptors.

Dosage

A light dose of peyote is 50-100g fresh or 10-20g dry, which equates in either case to roughly three to six mid-sized buttons. Moderate doses range up to 150g fresh or 30g dry (six to twelve buttons), while strong doses range up to 200g fresh or 40g dry (eight to sixteen buttons). Anything above this is considered heavy.

It is hard to be precise, however, due to the varying levels of mescaline in any given peyote button. Growing location and season of harvest can also affect their potency, as can age—older peyote tends to be more potent.

Download our FREE guide to learn how to begin a microdosing regimen, calibrate your dose level, and get the most out of your experience. “This FREE Guide was just what I needed to take the first step into Microdosing. AND IT WAS THE BEST DECISION OF MY LIFE! After starting my microdosing regiment I now have more focus, energy and clarity into what it is I truly want in this world.” Download our FREE guide to learn how to begin a microdosing regimen, calibrate your dose level, and get the most out of your experience. Everything you need to know about Microdosing in one place

James, New York Everything you need to know about Microdosing in one place

Benefits & Risks

04Potential Benefits

In the Native American Church, peyote ceremonies are used to treat a number of psychological, spiritual, and physiological issues. For many, a peyote journey offers deep insight into the self and the universe, giving one a greater sense of connection and spirituality. It’s also known for fostering compassion and gratitude and alleviating psychological disorders such as anxiety, depression, PTSD and addiction.

Peyote has also been shown to help people solve problems, access their creativity, be more environmentally conscious, and improve learning. In its original use, the plant medicine was also used to treat a number of ailments, including snake bites, wounds, skin conditions, and general pain.

Risks

Research into the harm potential and adverse effects of peyote is limited, but in general, it is considered a safe substance. A lethal dose has never been identified, probably because it’s too high to be taken accidentally.[7][8] In other words, to the best of our knowledge, nobody has ever died from a peyote overdose.

A 2005 study into the ceremonial use of peyote among Native American populations found no detrimental long-term effects.[9] It should be noted, though, that its use in other contexts may not be as safe—later studies have found an association between prior mental health problems and “bad trips.” Still, peyote appears to present little risk of flashbacks, or hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD). [10]

Peyote is traditionally consumed by Huichol women during pregnancy, but mescaline has been linked to fetal abnormalities and should be avoided by pregnant or breastfeeding women. [11][12]

Peyote can increase heart rate and blood pressure, so it should also be avoided by anyone with a heart condition and/or high blood pressure, particularly in combination with blood pressure medications. Other drugs to avoid combining with peyote include tramadol, immunomodulators, alcohol, and stimulants like cocaine and amphetamines.[13][14] Combining peyote with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) could increase nausea and may even be dangerous. In fact, the nausea that tends to arise from taking peyote alone may have something to do with the presence of naturally occurring MAOIs.[15][16]

Personal Growth

05A peyote trip is often characterized by personal blessings, healing, and insights, and many people emerge with an awareness of their place in the web of being. Some people who have taken part in peyote ceremonies have found that the experience allows them to confront their own shadow in order to move past it. [18] Beyond the subjective psychological experience, purging is another important aspect of the peyote ceremony and is thought to be useful for dispensing of deeply rooted fears and other negative emotions.[19]

While formal ceremonies have been developed and refined over many generations, maybe people are now finding the beneficial effects of peyote outside of a religious context. While these people may not believe the ceremonial setting is essential for attaining the profound and life-changing insights or transformations that peyote helps to bring about, indigenous peoples say otherwise. Ethically, it is also best to reserve the use of peyote for these settings. (See Ethical Considerations for more information.)

Solo, meditative peyote experiences can also give rise to insights into the nature of fear, the circle of life, immortality, better living, and so on. Prophetic visions are as common for solo users as those involved in peyote ceremonies, but in all settings, the plant should be approached with respect.[20] As one user put it, “if one does not respect the plant, the plant will certainly teach you to do so.”[18]

Peyote ceremonies can last upwards of 10 hours overnight and typically involve drumming, chanting, and prolonged periods of sleeplessness, along with social and behavioral interventions. They often involve prayers and spiritual practices for specific purposes, such as health and well-being, spiritual guidance for important decisions or journeys (such as for soldiers going off to war), or accepting the passing of a loved one. And many users find it helps to set up their intention in a similar way before consuming peyote, for instance by affirming their desire to learn.[21]

Therapeutic Use

06Peyote’s effect on the serotonin system likely has something to do with the treatment of substance addiction, but the set/setting and social support inherent in the traditional ceremony may have just as much if not more of a therapeutic effect. In addition to the sacrament of peyote, for instance, these ceremonies feature a master guide, marathon group sessions, ego reduction techniques, social networks, and a focus on self-actualization throughout.

As a traditional addiction therapy, the peyote ceremony can also provide an addict with visions of his or her eventual ruin, effectively simulating what alcoholics refer to as “rock bottom” and sparking a very real sense of urgency to change. The trance-like state of a ceremony’s continuous drumming and chants can also increase self-awareness, break down denial mechanisms, and give addicts a sense of control. [25]

In addition to its direct effects on the serotonin system, peyote is also associated with a strong “afterglow” effect that can last for up to 6 weeks after a ceremony. During this period, users commonly report feeling happier, more empathic, less prone to cravings, and more open to communication—all of which is likely to boost the efficiency of follow-up therapy sessions. Of course, this has obvious implications for the treatment of depression as well, especially given that depression scores are reportedly lower among more active members of the Native American Church.[24]

In fact, studies suggest that mescaline may increase blood flow and activity in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain in charge of planning, problem-solving, emotional regulation, and behavior. Low activity in this area is linked to depression and anxiety, leading scientists to hypothesize that mescaline could help alleviate symptoms of these disorders.

If you want to find out more about the topic check out our podcast interview with Dr. Joe Tafur M.D. where we talk about How Peyote and a Native American spirit walk created new opportunities to find hope or Click here to read the transcript

Mescaline could also help reduce suicidal thoughts, according to researchers at the University of Alabama. Using data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, the researchers found that people who have used a psychedelic drug at least once in their life show lower rates of suicidal thinking.

A 2013 study also found that lifetime mescaline or peyote use was significantly linked to a lower rate of agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder where subjects perceive their surrounding environment to be threatening.

Are you feeling drawn to work with plant medicines? Third Wave’s vetted Psychedelic Directory offers an honest, in-depth guide to safely accessing these substances.

Legality

07Legality of peyote in the United States

In the United States, despite it being a federally controlled Schedule I substance—even in its natural state—peyote is legal for members of the Native American Church under the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. And even non-Indians may be permitted to use it as part of “bona fide” ceremonies or serious research.[24][26][27][28]

Peyote can also be consumed with relative freedom—regardless of religious affiliation—in the City of Oakland, CA, which decriminalized all “entheogenic plants” containing indoleamines, tryptamines, or phenethylamines, making it legal for adults aged 21 and over to consume peyote and other plant medicines—regardless of ethnicity and religious affiliation. It also specifically decriminalizes (or rather deprioritizes for law enforcement) their cultivation and distribution.[29][30]

Legality of peyote in Mexico

Peyote is also a Schedule I substance in Mexico, where harvesting the plant from the wild is controlled due to peyote’s endangered status. Again, however, religious use is permitted.[26]

Legality of peyote in Canada

In Canada, although extracted mescaline is illegal, fresh (not dried) peyote and other mescaline-containing cacti are specifically exempt from scheduling.

Legality of peyote in the UK and elsewhere

The situation is much the same in the UK (even after the Psychoactive Substances Act) and elsewhere in Europe, where it tends to be legal to grow peyote but not to prepare it for use.[31]

In Australia, the legality of peyote varies by state. For example, it is illegal in Western Australia, Queensland, and the Northern Territory, but legal to grow (as long as it’s not for use) in Victoria and New South Wales, among other states.[2]

Ethical Considerations

08Peyote only grows naturally in Northern Mexico and small areas in South and West Texas. It’s also a slow-growing cactus, taking more than 10 years to mature from seed. Add to the mix the rampant and ongoing issues of unsustainable harvesting practices, the black market, and the prohibition of peyote cultivation, and what you get is a rapidly declining population lacking the ability to replenish.

This shortage of peyote endangers native traditions that have been in practice for generations. In fact, recent efforts to decriminalize plant medicines at the local level have been denounced by the Native American Church, which argues that loosening these laws sends the message to non-native people that peyote is legal, further threatening its habitat and the sacrament surrounding it.

Regardless of decriminalization, the renewed interest in plant medicines more generally has created a demand—and market—for peyote ceremonies that take place outside of the context and long history of indigenous traditions. This, of course, further erodes and endangers the cultures that peyote is native to. Some people see “exotic” spiritual practices such as peyote ceremonies as a replacement for the declining organized religions of the west. But these often provide only the appearance of authenticity compared to their familiar religious and spiritual practices. This has led to the perpetuation of the “noble savage” stereotype, which sees indigenous cultures denigrated by Westerners while select cultural practices are lauded—and eventually watered down so much that they’re washed away.

In Third Wave’s Ultimate Guide to Safely Sourcing Psychedelics, you will discover an astonishing menu of psychedelic medicines… In Third Wave’s Ultimate Guide to Safely Sourcing Psychedelics, you will discover an astonishing menu of psychedelic medicines… Beyond LSD and Psilocybin is a field. This guide will take you there.

…and how to source them without legal risk. Beyond LSD and Psilocybin is a field. This guide will take you there.

…and how to source them without legal risk.

History & Stats

09Brief History

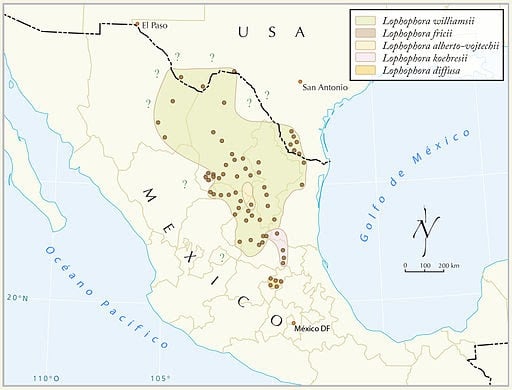

The traditional use of peyote is thought to have originated among the Tonkawa or Mescalero tribes of Texas and New Mexico, but it also has strong cultural ties with the Chichimeca and Tarahumara (Rarámuri), as well as the Cora (Náayarite), Huichol (Wixáritari), and other groups who adopted its use later.[32][33] Given the size of peyote’s native habitat, which extends from the north of the Rio Grande in Texas to the Chihuahuan Desert and Tamaulipan mezquital in Mexico, its use may well have originated independently among a variety of Native American tribes.[7]

Traditional uses are diverse and are not limited to ritual. The Tarahumara, for example, have used it for long-distance endurance foot races and as a topical treatment for wounds, burns, and painful joints.[34][35] Among the Huichol, it has also been used by pregnant and breastfeeding mothers.[11]

The first non-natives to encounter peyote use in the Americas were probably Catholic missionaries and conquistadors during the 16th century. Spanish friar Bernardino de Sahagún, for instance, described a Huichol peyote ceremony held in the desert and estimated that such practices may have been at least 1,980 years old. In referring to the cactus, he used the original Nahuatl name, peiotl, meaning “cocoon silk” in reference to the woolly tuft that sprouts from the depressions of the “button.”[33] Unfortunately, the massive destruction of Aztec records by earlier conquistadors means that little is known for certain.[34] More recently, with evidence from the Shumla Caves site in Texas, researchers have been able to date ceremonial peyote use to at least 5,700 years ago.[36]

During the conquest of the New World, peyote was near-universally condemned by Europeans who associated its use with devil-worship, cannibalism, and witchcraft, and attempted to stamp it out. One persistent peyote user, an Acaxee from Mexico, is said to have had his eyes gouged out as punishment and his stomach sliced open in the shape of a crucifix, leaving dogs to eat his insides. Suppression of the use of peyote continued throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries too—particularly after Native Americans had been forcibly displaced to reservations.[33][34]

At the same time, the ceremonial use of peyote became all the more important to Native Americans as an emblem of their emerging pan-Indian identity and their ongoing struggle against the so-called “manifest destiny” of their oppressors. Of course, it was also a means of coping spiritually with the subordination and loss of their culture.[33] As a result, native groups formerly at war with each other began to cooperate in a spirit of amicability, spreading peyote use beyond the Southwest to the Great Plains, the Midwest, and even into Canada.[37]

During this process, the traditional peyote ceremony was overlaid with Christian elements to help safeguard the new religion as a legitimate form of Christian worship. For example, Jesus was invoked alongside animal spirits, and the “peyote road” (right way of living) was conflated with Christian values. Upon the altar, the “roadman” who led the ceremony not only kept a large sacred peyote button (the “Peyote Chief” or “Father Peyote”) but also a Christian Bible.[33] Interestingly, Peyotism, as it was called, was devoid of all the usual Christian guilt. In fact, it positioned Native Americans as much closer to God than whites, since it was “the whites,” they said, who crucified Jesus—not the ancestrally separated Indians.[34]

By 1885, despite sustained opposition from missionaries and government officials, the precursor to the Native American Church (NAC) of today was more or less fully established.[33] It was formally registered with a charter in 1918 and, by the 1940s, had opened branch chapters throughout the United States, Canada, and Mexico.[37]

In 1960, a landmark court case, presided over by Arizona Judge Yale McFate, finally legitimized peyote as having “a similar relation to the Indians—most of whom cannot read—as does the Holy Bible to the white man.” He also pointed out that suppression of its use was unconstitutional since it obstructed religious freedom.[38] By this time, the NAC had roughly 225,000 members (up from 13,300 in 1922) and when peyote (not just mescaline) was classified Schedule I under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, a special exemption was made for religious use among Native Americans.[37][34] But it wasn’t until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 that it was truly enshrined as a right. Amendments in 1994 clarified and extended this right to all 50 states.[39]

Of course, none of this progress took place in isolation. As early as the late-1800s/early-1900s, non-native intellectuals and scientists—including the neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell, the philosopher William James, and the occultist Aleister Crowley—were experimenting with peyote for themselves.[40][41] In fact, the drug company Parke-Davis was even promoting their own liquid peyote extract as an effective “cardiac tonic” (with no mention whatsoever of its psychoactive effects).[37] Other in-depth studies, conducted by German and Austrian scientists, led to the isolation of mescaline in 1897 and its synthesis—the first of any psychedelic—in 1919.[34][42]

Later, in 1947, having learned of Nazi experiments exploring mescaline as a possible “truth serum,” the US government began its own secretive program along the same lines, codenamed “Project CHATTER.”[43] This project later gave up on mescaline and turned its attention to LSD, but was ultimately deemed a failure in 1953.

In the same year, Aldous Huxley first tried mescaline under the supervision of psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, an experience he described in The Doors of Perception as more valid than consensus reality—showing him “for a few timeless hours the outer and the inner world, not as they appear to an animal obsessed with survival or to a human being obsessed with words and notions, but as they are apprehended, directly and unconditionally, by Mind at Large … an experience of inestimable value to everyone and especially to the intellectual.”[44] Two years later, as part of a documentary for the BBC, Osmond also gave mescaline to a British Member of Parliament, his friend Christopher Mayhew. And while Mayhew described his own experience in terms similar to Huxley’s, as a state of complete bliss outside of time and space, a committee of “experts” evidently disagreed with its validity and the footage never aired.[45][46]

Nevertheless, peyote was becoming well known. Throughout the 1960s, a number of anthropologists accompanied the Huichol on peyote hunts (spiritual journeys to gather the cacti) and in 1968 Carlos Castaneda published The Teachings of Don Juan with his own firsthand accounts of peyote visions.[33][44]

Listen to our podcast episode with Jesse Jarnow talking about The Psychedelic History Of America or Click here to read the transcript

Current usage

According to the Global Drug Survey in 2014, mescaline or peyote were only among the top 20 drugs for past month usage in Mexico. Peyote was taken by 6.4% and mescaline by 4.4% of 643 Mexican survey respondents.[47]

Of course, we cannot generalize current usage statistics from such limited data, but it does give us some idea of its popularity relative to other substances. Unfortunately, precise usage statistics for peyote aren’t really available because surveys tend to lump it together with other substances like LSD, psilocybin, and MDMA. Hence, SAMHSA’s 2014 finding that 0.4% of the US population used “hallucinogens” in the past month is more or less meaningless.[48]

That said, we can trace the popularity of peyote over time by looking at its appearance in publications and Google searches. The number of publications related to peyote and mescaline peaked in the 1940s and 50s, followed by a much larger spike in the 1960s and 70s—during the psychedelic revolution and roughly coinciding with the publication of Carlos Castaneda’s books. Interest spiked again in the 1990s, presumably due to the Mexican government’s 1991 listing of peyote as an endangered species and the 1994 amendments to the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.[49] Published mentions steadily decreased over the next decade or so, possibly because of the rising popularity of other psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin.

Google searches, meanwhile, have remained fairly steady for peyote since 2004—although searches for mescaline have decreased. Searches for peyote did reach an all-time high in December 2014 (and again in May 2015) but this was most likely in relation to its appearance in the video game Grand Theft Auto V. Unsurprisingly, most Google searches for peyote come from Mexico, the United States, and Canada. (The popularity of the search term in Uruguay likely has more to do with the Uruguayan band El Peyote Asesino.)

Where does peyote grow?

The peyote cactus grows primarily in Mexico—in the Chihuahuan Desert and the scrublands of Coahuila, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and San Luis Potosí. It also grows in the American Southwest. You can often find peyote in Texas and New Mexico, for instance.

The map below shows a rough outline of traditional peyote locations. For ceremonial practitioners, this has long been the grounds where peyote is collected in the wild.

Peyote plant locations have shifted and diminished over time, though. In some regions where the cactus once thrived, there may now be none whatsoever.

Myths

10“There are two species or types of peyote”

Some Native American tribes identify two species or types of peyote, which the Huichol call Tzinouritehua-hikuri (Peyote of the God) and Rhaitoumuanitari-hikuri (Peyote of the Goddess) in reference to their differing size, potency, and palatability. Botanists, however, recognize only one species of peyote: Lophophora williamsii. This is the peyote Native American tribes have venerated for millennia. The superficial differences are instead attributed to other factors, such as age.[5]

There is another species in the Lophophora genus, the Lophophora diffusa, that looks remarkably like peyote, but it contains only trace amounts of mescaline—and sometimes none whatsoever. Instead, this so-called “false peyote” contains high levels of the narcotic alkaloid pellotine.[50]

“Peyote is legal in the United States”

The legal status of peyote in the US can be confusing, but by and large, the consumption of peyote is illegal—it is, after all, a Schedule I substance. However, peyote is legal for members of the Native American Church under the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. Non-Indians may be permitted to use it as part of “bona fide” ceremonies or serious research, and in the City of Oakland, its use has been decriminalized, but it is not legal in the true sense of the word. See Legality for more information.

FAQ

11Can it be detected in a drug test?

Mescaline can be detected in the urine for one to four days after use, but it’s not included in either standard or extended drug screens.[51] Virtually all labs require a specific test for the substance, so unless your employer is a real stickler and worried that you’ve been spending your free time at peyote ceremonies, you should be fine.

Is peyote illegal unless you’re in the Native American Church?

It depends on your state. In many states a special exemption is made for members of the Native American Church (NAC) to use peyote “in bona fide religious ceremonies,” often regardless of race or tribal membership. But in other states, including Arizona, peyote is legal (or tolerated) for any bona fide religious organization, whether the NAC or not. Check with your local authority for up-to-date laws.

What does peyote do?

Peyote commonly produces visions and philosophical or introspective insights. For more on the peyote experience, see Experience.

Can peyote cause psychological trauma?

If you follow the 6Ss of psychedelic use and avoid taking peyote if you have a family history of mental health issues, there appears to be very little chance of long-term psychiatric issues.

Of course, peyote can make you feel crazy in the short term (acute psychosis), especially if you don’t follow the 6Ss, and this is colloquially known as a “bad trip.”

What does peyote look like?

The features that define peyote include:

- Small, globose shape, often growing in clumps

- Thick, waxy, green or blue-green skin

- Uneven ribs of varying number

- Sticky, yellow-white tufts; no spines

- Occasional pink or white peyote flower or flowers on top

Where to buy peyote?

Many people find peyote for sale online. While that means that reputable suppliers are just a click away, it’s important to understand that buying it this way could mean supporting illegal or unsustainable harvesting practices—as well as contributing to the peyote shortage among Native Americans who use peyote for religious purposes. See Ethical Considerations for more information.

Is peyote legal to grow?

Peyote is legal to grow in many countries even where mescaline is illegal, but this doesn’t include the United States (with some notable exceptions). In many countries, you can buy peyote seeds and living buttons to grow at home. Always check your local laws before cultivating peyote and be aware that, while it’s a relatively low-maintenance cactus to grow, it may take several years to establish a decent-sized garden.[52] If growing peyote from seed, it’ll probably take decades. There are numerous resources online for learning how to grow peyote at home.

Because it’s an endangered species, growing peyote at home—whether from cuttings or peyote cactus seeds—could help to save it from extinction. In fact, wild peyote should never be picked from unless by licensed peyoteros for use in Native ceremonies.

How long does peyote last in storage?

Peyote buttons appear to retain mescaline for an exceptionally long time—potentially even thousands of years.[53] The key (once thoroughly dried) is proper storage in cool, dark, dry conditions, ideally in an airtight container.

How do you take peyote?

Peyote buttons can be eaten whole or brewed as peyote tea. A moderate dose of 200-400 mg mescaline can be achieved by ingesting around six buttons.

Can you smoke peyote?

Smoking peyote is generally ineffective. And smoking extracted mescaline salts isn’t recommended either.

What is pomada de peyote?

Pomada de peyote in English basically means “peyote gel.” This Mexican peyote cream or ointment, which also contains marijuana, is sold as a remedy for aches and pains, cramps, coughs, angina, and other conditions. Although part of an eons-old tradition of medicinal use, it appears to be a relatively new preparation of peyote cactus for sale in Mexico. In 2016, U.S. Customs and Border Protection issued a reminder of its Schedule I status.[54]

Can I microdose with peyote?

Peyote can be microdosed by ingesting around half a button (20-40 mg mescaline) every four days or so. In fact, this may be one of its traditional uses; the Tarahumara Indians are said to consume small amounts of the cactus to combat hunger and fatigue while hunting.[55] In general, though, and certainly to avoid nausea, it may be preferable to microdose pure mescaline (and, given the endangered status of peyote, San Pedro may be a preferable source). For more information, check out our Essential Guide to Microdosing Mescaline.

What is peyote’s mescaline content compared to San Pedro and Peruvian torch?

Peyote’s mescaline content is typically 1-6% by dry weight, tending toward the low-middle part of this range. The mescaline content of San Pedro (T. pachanoi) and Peruvian torch (T. peruvianus) is less in general. But in both cacti it tends to be highly variable. In San Pedro, mescaline content is said to range between 0.025% and 2.375% by dry weight, and Peruvian torch has been found to contain up to 0.817% mescaline by dry weight and sometimes none at all.[56]

What’s peyote’s tolerance effect?

Peyote generally produces a tolerance that lasts several days, and it also produces cross-tolerance to other psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin. The potency of each will likely be diminished for a little while after taking peyote. It’s therefore recommended to wait several days between doses of any of these substances.[57]

Can I mix it with other drugs?

Peyote should never be mixed with tramadol, as it can lead to serotonin syndrome. Also avoid mixing peyote with alcohol, cannabis, amphetamines or cocaine. Click here for a detailed chart of safe drug combinations.

Footnotes

12[1] Tsetsi, E. (2014, Jan). Arizona Church Offers Peyote-Induced Spiritual Journeys. Retrieved from http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/news/a-remote-arizona-church-offers-peyote-induced-spiritual-journeys-6460988.

[2] PsychonautWiki. (2018, Feb 21). Mescaline. Retrieved from https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Mescaline.

[3] Wilson, R.A. (1977). Cosmic Trigger: Final Secret of the Illuminati, Volume I. Las Vegas, NV: New Falcon Publications.

[4] Castaneda, C. (1968). The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

[5] Trenary, K. (1997, May). Visionary Cactus Guide – Lophophora. Retrieved from http://www.lycaeum.org//~iamklaus/lophopho.htm.

[6] PsychonautWiki. (2018, Dec 29). Psychedelic cacti. Retrieved from https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Psychedelic_cacti#Alkaloids_in_different_Lophophora_species.

[7] Jones, P.N. (2005). The American Indian Church and its sacramental use of peyote: A review for professionals in the mental-health arena. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8(4):277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670412331304348

[8] Speck, L.B. (1957). Toxicity and effects of increasing doses of mescaline. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 119(1):78-84. Retrieved from https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.891.6555&rep=rep1&type=pdf

[9] Halpern, J.H., Sherwood, A.R., Hudson, J.I., Yurgelun-Todd, D., Pope, H.G. Jr. (2005). Psychological and cognitive effects of long-term peyote use among Native Americans. Biological Psychiatry, 58(8):624-31. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.038.

[10] Halpern, J.H., Pope, H.G. Jr. (2003). Hallucinogen persisting perception disorder: What do we know after 50 years? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69(2):109-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00306-X.

[11] Meyer, S. (2011, May 24). Should I Use Peyote If I Am Pregnant or Breastfeeding? Retrieved from http://nativemothering.com/2011/05/should-i-use-peyote-if-i-am-pregnant-or-breastfeeding/.

[12] Gilmore, H.T. (2001). Peyote use during pregnancy. South Dakota Journal of Medicine, 54(1):27-9. Retrieved from https://europepmc.org/article/med/11211421

[13] Natural Standard. (2011). Peyote. Retrieved from http://www.healthprioritiesinc.com/ns/DisplayMonograph.asp?StoreID=c8ad0990cf0d44a5bac9118cf4159a55&DocID=bottomline-peyote.

[14] Therapeutic Research Faculty. (2009). PEYOTE: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions and Warnings – WebMD. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/vitamins-supplements/ingredientmono-473-peyote.aspx?activeingredientid=473&activeingredientname=peyote.

[15] Ask Erowid. (2007, Mar 8). Are MAOIs dangerous in combination with some Trichocereus cacti? Retrieved from https://erowid.org/ask/ask.php?ID=3089.

[16] PsychonautWiki. (2018, Feb 11). MAOI – Interactions. Retrieved from https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/MAOI#Interactions.

[17] Jones, P.N. (2007). The American Indian Church and its sacramental use of peyote: A review for professionals in the mental-health arena. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8(4):277-290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670412331304348.

[18] lunarvilly. (2017, Dec 18). A Meeting with God: An Experience with Peyote (exp103851). Retrieved from https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=103851.

[19] Peyotero. (2002, May 2). Sacred Medicine: An Experience with Peyote (exp11657). Retrieved from https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=11657.

[20] Joel. (2003, Sep 29). The Plant with the Answer: An Experience with Peyote (exp27201). Retrieved from https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=27201.

[21] Medicine_Man. (2018, Jan 4). Induced Transcendence: An Experience with Peyote & Meditation (exp103143). Retrieved from https://erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=103143.

[22] Winkelman, M.J. (2015). Psychedelics as Medicines for Substance Abuse Rehabilitation: Evaluating Treatments with LSD, Peyote, Ibogaine and Ayahuasca. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 7(2):101-16. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874473708666150107120011.

[23] Pacific Standard Staff. (2016, Oct 10). What’s behind the myth of Native American alcoholism? Retrieved from https://psmag.com/news/whats-behind-the-myth-of-native-american-alcoholism.

[24] Horgan, J. (2009, Jan 12). Curing Drug and Alcohol Addiction with Peyote. Retrieved from http://discovermagazine.com/2009/the-brain/peyote.

[25] McClusky, J. (1997). Native American Church Peyotism and the Treatment of Alcoholism. Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), 7(4):3-4.

[26] Erowid. (2016, Sep 7). Peyote – Legal Status. Retrieved from https://erowid.org/plants/peyote/peyote_law.shtml.

[27] DEA. Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations. §1307.31 Native American Church. Retrieved from https://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/cfr/1307/1307_31.htm.

[28] Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. U.S. v. Boyll, 774 F.Supp. 133 – September 3, 1991. Retrieved from http://www.druglibrary.org/olsen/religion/boyll.html.

[29] AP. (2019, Jun 5). The Latest: Oakland 2nd US city to legalize magic mushrooms. Retrieved from https://www.apnews.com/ff023dfbf4534eba8622f504d272ff00.

[30] Decriminalize Nature Oakland. Resolution. Retrieved from https://www.decriminalizenature.org/dno-resolution.

[31] DrugWise. (2017). Cacti. Retrieved from http://www.drugwise.org.uk/cacti/.

[32] Stewart, O.C. (1987). Peyote Religion: A History. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

[33] Schultes, R. E., Hofmann, A., Rätsch, C. (2001). Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

[34] Stafford, P. (1992). Psychedelics Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Ronin Publishing.

[35] Lophophora williamsii: Peyote. (2006). Medicial Properties. Retrieved from http://bioweb.uwlax.edu/bio203/2011/toellner_kayl/Medical.htm.

[36] El-Seedi, H.R., De Smet, P.A., Beck, O., Possnert, G., Bruhn, J. G. (2005). Prehistoric peyote use: alkaloid analysis and radiocarbon dating of archaeological specimens of Lophophora from Texas. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 101(1-3):238-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.022.

[37] Choffnes, D. (2016). Nature’s Pharmacopeia: A World of Medicinal Plants. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

[38] Court Decision Regarding Peyote and the Native American Church [Letter to the editor]. (1961, Dec). American Anthropologist, 63(6):1335-37. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1961.63.6.02a00150.

[39] 42 U.S. Code § 1996a -Traditional Indian religious use of peyote.

[40] Trochu, T. (2008). Investigations into the William James Collection at Harvard: An interview with Eugene Taylor. William James Studies, 3. Retrieved from http://williamjamesstudies.org/investigations-into-the-william-james-collection-at-harvard-an-interview-with-eugene-taylor/.

[41] OPEN Foundation. (2016, Jun 5). Peyote and Aleister Crowley – Patrick Everitt [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ll41StGTTxc.

[42] Späth, E. (1919). Über die Anhalonium-Alkaloide. I. Anhalin und Mezcalin. Monatshefte für Chemie, 40(2):129-154. https://doi.org10.1007/BF01524590.

[43] Alliance for Human Research Protection. (2015, Jan 18). 1947–1953: Navy’s Project CHATTER tested drugs for interrogation. Retrieved from http://ahrp.org/1947-1953-navys-project-chatter-tested-drugs-for-interrogation/.

[44] Huxley, A. (1954). The Doors of Perception. London: Chatto & Windus.

[45] sotcaa. (2005, Feb). Panorama: The Mescaline Experiment – Page 4. Retrieved from http://sotcaa.org/hiddenarchive/mayhew04.html.

[46] MrVoltix. (2010, Oct 16). The Mescaline experiment: Humphry Osmond and Christopher Mayhew [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hd4rgyZzseY&t=87s.

[47] Global Drug Survey GDS2014. (2014). Last 12 Month Prevalence of Top 20 Drugs. Retrieved from https://www.globaldrugsurvey.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/last-12-months-drug-prevalence.pdf.

[48] SAMHSA. (2015, Oct 30). Hallucinogens. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/atod/hallucinogens.

[49] DeKorne, J. (2011). Psychedelic Shamanism (Updated ed.). Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

[50] PsychonautWiki. (2018, Jan 8). Lophophora diffusa (botany). Retrieved from https://psychonautwiki.org/wiki/Lophophora_diffusa_(botany).

[51] Erowid. (2015, Feb 10). Mescaline – Drug Testing. Retrieved from https://erowid.org/chemicals/mescaline/mescaline_testing.shtml.

[52] Peyote Growing Tips. (2015, Feb 10). Retrieved from https://erowid.org/plants/peyote/peyote_cultivation1.shtml.

[53] Erowid. (2005). Storage Basics: What Is The Shelf Life of Peyote? Erowid Extracts 9:9. Retrieved from https://erowid.org/plants/peyote/peyote_article2.shtml.

[54] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. (2016, Aug 17). CBP Reminds Public that Peyote is a Prohibited Item. Retrieved from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/local-media-release/cbp-reminds-public-peyote-prohibited-item.

[55] insidemymind108. Tarahumara Indians Microdosing Peyote [Online forum comment]. Message posted to https://www.reddit.com/r/microdosing/comments/2nle72/tarahumara_indians_microdosing_peyote/.

[56] Trout, K. (2014). Cactus Chemistry By Species. Mydriatic Productions. Retrieved from https://troutsnotes.com/pdf/CactusChemistry_2013_Light.pdf.

[57] CESAR. (2013, Oct 29). Peyote – Addiction and Tolerance. Retrieved from http://www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/drugs/peyote.asp#addiction.

In Third Wave’s Ultimate Guide to Safely Sourcing Psychedelics, you will discover an astonishing menu of psychedelic medicines… In Third Wave’s Ultimate Guide to Safely Sourcing Psychedelics, you will discover an astonishing menu of psychedelic medicines… Beyond LSD and Psilocybin is a field. This guide will take you there.

…and how to source them without legal risk. Beyond LSD and Psilocybin is a field. This guide will take you there.

…and how to source them without legal risk.