Episode 68

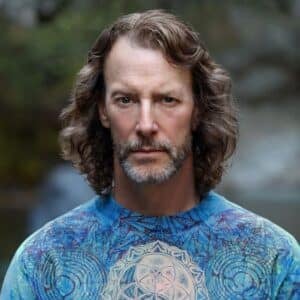

Douglas Rushkoff

Douglas Rushkoff, best-selling author and one of the world’s ten most influential intellectuals, joins host Paul Austin to discuss what it means to be human.

In a Western world beset by technological distraction and a never-ending thirst for more, what role do psychedelics play in cultivating mystery, awe, and reverence? Further, why is it so important to embrace these elements – mystery, awe, and reverence – as part of our human nature?

—

Named one of the “world’s ten most influential intellectuals” by MIT, Douglas Rushkoff is an author and documentarian who studies human autonomy in a digital age. His twenty books include the just-published Team Human, based on his podcast, as well as the bestsellers Present Shock, Throwing Rocks and the Google Bus, Program or Be Programmed, Life Inc, and Media Virus. He also made the PBS Frontline documentaries Generation Like, The Persuaders, and Merchants of Cool. His book Coercion won the Marshall McLuhan Award, and the Media Ecology Association honored him with the first Neil Postman Award for Career Achievement in Public Intellectual Activity.

Rushkoff’s work explores how different technological environments change our relationship to narrative, money, power, and one another. He coined such concepts as “viral media,” “screenagers,” and “social currency,” and has been a leading voice for applying digital media toward social and economic justice. He a research fellow of the Institute for the Future, and founder of the Laboratory for Digital Humanism at CUNY/Queens, where he is a Professor of Media Theory and Digital Economics. He is a columnist for Medium, and his novels and comics, Ecstasy Club, A.D.D, and Aleister & Adolf, are all being developed for the screen.

Podcast Highlights

- Why Western civilization is in a "roid-rage" moment - and what it means for the potential collapse of our entire society

- When the human story went from being circular to linear - and what this meant to the identity of each human being

- Why Rushkoff isn't optimistic about technology's ability to solve technology's problems

Show Links

Podcast Transcript

0:00:26 Paul Austin: Named one of the world's 10 most influential intellectuals by MIT, Douglas Rushkoff is an author and documentarian who studies human autonomy in a digital age. His 20 books include the just published Team Human based on his podcast, as well as best-Sellers Present Shock, Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, Program or Be Programmed, and Life Inc. He has also made PBS Frontline documentaries, including Generation Like, The Persuaders, and Merchants of Cool. Rushkoff 's work explores how different technological environments change our relationship to narrative, money, power, and one another. He coined such concepts as viral media, screen-agers, and social currency, and has been a leading voice for applying digital media toward social and economic justice.

0:01:15 PA: Folks, this is a fucking fantastic interview. Rushkoff came over to my place in New York in early August. We sat down for a couple of hours and we talked about what it means to be human in a world that's becoming increasingly anti-human. Including why western civilization is a roid-rage moment and what it means for the potential collapse of our entire society, when the human story went from being circular to linear and what this meant to the identity of each human being, and why Rushkoff isn't optimistic about technology's ability to solve technology's problems. This is a great one, I can't wait for you to really get into it. So without further ado, I bring you Douglas Rushkoff.

0:02:03 Douglas Rushkoff: If you can't be progressive anymore because progressing means that what you did 10 years ago is no longer good and now you're out of the club, then who's gonna wanna progress?

0:02:15 PA: You just wrote about this on Medium, right?

0:02:16 DR: Yeah, circular firing squad of the left.

0:02:18 PA: It is.

0:02:19 DR: Yeah, it bothers me.

0:02:20 PA: Yeah. Why, what does that mean? Explain that a little bit just for...

0:02:25 DR: Well, there's... I get that we don't like old lefty-politicians anymore, right? 'Cause they're old and we're young, and we want the next AOC or whatever, and that's great. But the forefathers of the Progressive Movement, they're the people who fought for civil rights and did all this stuff in the 60s and 70s and 80s. And if you're gonna yell at somebody for something they said in 1980 that was progressive at the time, but now because of the language, is considered insensitive to what we currently understand, that's a big problem. It's like, okay, so someone called black people colored in 1980 when there was the National Association of Early Advancement of Colored People was the organization. You can't yell at somebody for that. The question is not where were they 30, 40 years ago? It's where have they come, what did they learn? If you can't let people change and develop then you don't want living humans in your world. And the thing is, I guess what I'm looking at these days is that fascism rubs both ways. Fascism is not the particular content of the fascist side. Fascism is also the unforgiving, absolutist approach to everything.

0:03:49 PA: The statist approach to some degree. Just assuming things will stay as they are.

0:03:54 DR: Yeah, and just being this kind of extremism is... I get it. We see racist fascist on the one side and then become anti-fascist fascist on the other side, and you can't... That gives the neo-right so much ammunition. When I'm in a faculty meeting at CUNY and another faculty member says, "Well, you can say that because you're a cis-white male." It's like I'm getting it from that side and at the same time there's people marching in South Carolina saying, "The Jews will not replace us." So to him, I'm not white. So it's like, "Okay, hey every... Just all you all can hate me." [chuckle]

0:04:42 PA: Yeah, you can't win. You can't win in this environment.

0:04:46 DR: So I get it, I get it. I could pass for white in many situations or be treated as white in a store that might follow me if they thought I was black 'cause they're scared I'm gonna shoplift. So I get it, I'm not gonna get that. But I can go to the South and also stand out like a sore thumb in certain situations and be like... And the questions I'll get asked as a Jew are just incredible, so it's funny.

0:05:08 PA: So extremism, extremism has been developing.

0:05:11 DR: Yeah, it's an interesting moment.

0:05:11 PA: Of significance, right? Yeah, yeah.

0:05:14 DR: It's an interesting moment in culture, right? It feels like there's a right-wing insurgency in America that if it kept going on the same trajectory, we're gonna go to civil war, right? [chuckle] It's gonna get increasingly violent. Then when you do the... I've got a friend at the Anti-Defamation League who does a mimetics project using my old stuff, my old media virus locus and stuff, but really mathematically and with computers and stuff. And they're looking at the frequency of certain kinds of hate speech and how it corresponds to hate crimes, and it doesn't look like a good trajectory unless something significant changes.

0:05:54 PA: People like Stephen Pinker, who say that life is getting better all the time and that the Western world is improving. So it seems like there are a lot of these arguments and counter-arguments, and people saying, "Well look, there's something to be grateful for, and this is beautiful, you have everything at your fingertips." At the same time, we look outside and there's another mass shooting happening and there's an ecological crisis under way, and it seems to be very paradoxical.

0:06:20 DR: Right. Well, it is and it's not. If you look at all the externalities of human technological scientific progress, all of a sudden it stops looking like progress. So, Pinker is talking as if, let's say you're feeling weak and you start taking steroids, you're gonna be stronger and you're gonna lift more today than you did yesterday and more tomorrow than you did today, and by all those metrics, you can say, "Look! Things are getting better! I'm awake more, I sleep less, I've got more muscle mass, I've got less fat, I'm lifting more stuff, I'm running faster." Yeah, but you're also closer to catastrophe, to death. This is not... What did you have to do to your liver, and kidneys, and brain, and spouse, in order to become a roid-raging maniac? So right, western civilization is in a roid-rage moment. And you could look at certain metrics have improved, but so many other ones have gotten worse. We're on a planet that can't support this rate of extraction. And what he's talking about... And let's play the real game here, right? So, I've got the same agent as he does, John Brockman, agent to the scientific stars, and these folks, when I go to their... When I would, in the 90s, go to kinda dinner parties and all, they...

0:07:51 PA: You don't go to the dinner parties anymore.

0:07:52 DR: No, I would, I'm not invited anymore. I was a promising, young whatever. But when I was at the dinner... And they would basically accuse me of being a moralist, of being kind of a superstitious... Even if I don't believe in God, I believe in a moral order, moral fabric to the universe which is God by any other name, that that makes me weird, superstitious, retrograde, like I'm never gonna amount to anything because I don't accept to cool, rational, amoral logic of the universe. And now we're finding out that these same scientists were flying down to Epstein's island, hanging out with him doing God knows what. And it's like, "Oh Okay, I get it. That's, amorality for you. That's if you have no moral core, then that's where you're gonna end up!" But they're taking an understanding of science that was forged in the late middle ages, early renaissance, by Francis Bacon. And Francis Bacon saw light and science as a way of getting rid of the dark feminine scary kind of stuff.

0:09:05 PA: The mystery.

0:09:07 DR: To get rid of the mystery. And even the language he used, I'm not just accusing him, the language he used was that, "Through science, we would be able to seize nature by the hair. Hold her down and subdue her to our will." So, he's using a rape fantasy to understand, to express the purpose of science. To take apart nature, and to all of it's cause and effect components, and to lose the Invivo-holism of what nature really is and...

0:09:43 PA: Atomize it, to mechanize it, to industrialize it.

0:09:46 DR: That's why it dove-tailed so well with corporate capitalism, and the industrial age, and repeatability, and Taylorism, and domination of workers and women. And the thing that you're doing, the thing we're doing now is saying, "Oh, wait a minute, it's time to retrieve the human values, the natural values, the female values, the indigenous values, that we forcibly repressed in order to build this scientific, mechanized, technologies horror show that we're living in."

0:10:16 PA: So Frankenstein, that we've created. Yeah.

0:10:18 DR: Yeah! She got it! Of course, it was the woman writing at the time who got it, but yeah. And some crazy romantic poets on Absinthe.

0:10:26 PA: And Opium, right?

0:10:27 DR: And Opium, yeah, but sometimes it's the drugged cultures who are able to hold themselves back from falling into whatever the dominant group thing is of that time.

0:10:39 PA: So then, when psychedelics came about in the 60s, the 50s and 60s for the first time, what did that reintroduction of altered states do to this mechanized industrial approach that we had been taking for hundreds of years by that point?

0:10:54 DR: Well, it's weird, it led to challenging of underlying assumptions. So, after Wasson exposed Leary to I guess it was mushrooms originally down in Mexico, he comes back, and he's changed, and he's looking at, "What am I taking for granted here?" That's sort of the main, I think, the main psychedelic insight. That I'm in a reality tunnel that has some underlying, accepted suppositions, which may or may not be true. So he goes back to Berkeley, and he's supposed to be doing I don't know whether it was his dissertation or it might have been his first work as a research psychiatrist. And he decided, "How do we know that psychiatry even makes people better?" So he did this experiment where he looked at the self-reported rate of cure of depressed people by comparing people who were on the wait list for Berkeley's Free Clinic and people who made it through the wait... Got through the wait list and got the therapy. There's some people on the wait list for three years, some people do therapy for three years. And the rate of improvement was the same. [laughter] Which got him kicked out, he got kicked out of Berkeley for that, but then Harvard took him, 'cause they were like, "You're a smart guy!" And that worked until of course he was caught doing drugs.

0:12:23 PA: Dosing on the drugs.

0:12:24 DR: Yeah, well, it was grads even, I think.

0:12:25 PA: It was that whole Andrew Weil, Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, thing.

0:12:30 DR: Yeah, it was an interesting crew. And they were doing real research and real work, but I think that actually getting kicked out of Harvard was what radicalized him. He wouldn't have had to be at Millbrook with a bunch of hippies and stuff if he was allowed to keep doing it as research. And it's funny, it's like now, finally, we're picked up where Leary's late 60s research at Harvard let-off, it's like now there's discipline studies being done about addiction and depression and everything else.

0:13:00 PA: The resurgence.

0:13:00 DR: Yeah.

0:13:00 PA: Of psychedelics.

0:13:00 DR: Resurgence. Right. So just as you're... But it's all about retrieval, that's the thing people don't realize. Progress is not about blank slate. That the Silicon Valley understanding of innovation and progress is that you come up with something completely new. Now whereas, the intelligent and more indigenous understanding of innovation is you retrieve something really old. Now... Oh, my grandmother used to do this or the indigenous people of this region used to do that, and so when we're looking at things like crop rotation and soil management, it's like, oh we can go to Monsanto for some patentable new solution to growing crops on dead dirt. Or we could retrieve the techniques we'd learned for how do you steward soil, how do you engage with the living earth.

0:13:51 PA: When the difference between those two, I think, comes back to what you were mentioning earlier, which is externalities.

0:13:54 DR: Yeah...

0:13:56 PA: The wisdom traditions, these traditions that have been carried on for sometimes thousands and thousands of years, the reason that's been the case is because, in some degree, it minimizes the second and third order consequences that we just don't have the awareness to understand, whereas, you know Taleb, Antifragile and Black Swan.

0:14:13 DR: Yeah.

0:14:13 PA: He calls this the Lindy Effect, which essentially, he knows if he's gonna read a book, that it's more likely that he'll read it if it's been around for 500 years compared to five months because the fact that it's still around after 500 years shows that that book has a lot of wisdom and tradition and understanding and...

0:14:31 DR: Right. And a lot of kids today would say the opposite. The fact that it's been around 5000 years and nothing changed means that we need a new solution, we need something else. Yet, when you look at... A lot of my fiction goes into, into the Bible or into Torah, because there's such stuff in there, it's so rich. It's funny, a friend of mine, Grant Morrison, this comic book guy, always looks back to early Superman and early Batman, that's like his kinda source material to play with these giant archetypes. And for me, I go back to the Bible, but in some ways it's the same sort of pantheon of Gods, and matriarchs, and characters going through these very mythic situations that happen again.

0:15:21 PA: The hero's journey.

0:15:23 DR: Yeah...

0:15:24 PA: That means... I think this is what the work of Joseph Campbell then did to popularize what it meant to be human, and what it meant to be human over thousands and thousands of years, and how the human story is something that we all share, that we all have in common, that makes us really not that different from one another.

0:15:39 DR: Yeah. And part of what I'm looking at is when did the story go from being circular to being linear? So, with the invention of text and... The Jews started to write down Torah. And the invention of text is what gave us history, 'cause we could write down what happened, and it gave us a future 'cause we could have contracts and agreements that could be... That would project into the future. So once we had a past, present, and future, all our understandings of life and the world changed. The beauty of it is that the Jews kind of invented progress, with linear time, "We can be better next year than we were this year. Next year in Jerusalem, the Messianic Mashiach will come in the future, let's work towards that," which is a beautiful thing. The problem with it though, is it led to this kind of understanding of the past is almost kind of a dumping ground. It's like progress becomes, like for the billionaires today, "How can I build a car that goes fast enough so I never have to breathe my own exhaust?" So there's this kind of pat... And we just keep going, keep going. The future is all that matters. Everything's new, everything's renovated. And you move... We move slowly, west west west west, until you get to California where it's all still about, "Forget the past, but move to the future. Don't worry about reparations and black people and all the stuff that you've stepped on. It's still... "

0:17:12 PA: Don't worry about the karmic debt that you've created over 300 years of industrialization and that you now have to face and come to terms with, in order to actually...

0:17:23 DR: We're gonna come up with something new...

0:17:25 PA: Yeah...

0:17:26 DR: New, new, new...

0:17:26 PA: Yeah...

0:17:27 DR: It's okay. Monsanto will get us out. The only way out is through. And I would agree that we can't go back, but the way we go forward is by retrieving and bringing forward. We draw forward from the past rather than just trying to go blindly ahead. But business and advertising didn't help with that either. We're taught to look at our parents, this is not your father's automobile, it's not your father's Judaism, it's not... "You're doing it new, don't worry." It's like there's uncomfort in where we came from, especially when you look forward, if all people can imagine looking forward is the fucking zombie apocalypse, then maybe we should retrieve something else.

0:18:11 PA: In your study, in your work, what examples have you found of that? Of people who are doing this, of organizations who are going back to that, of societies that are really trying to retrieve the past, so to say, to bring it here now to help humanity...

0:18:29 DR: Well, interestingly enough, your microdosing community is sort of that. Let's take an ancient technology and bring it forward in a way that white, Western people can understand. And sort of like when Maharishi got imported to America by the Beatles, and he looks and goes, "Okay. How can I set up meditation in a way that these people will do it. Two 20 minutes, is it? Two 30 minute sessions a day, give them a single mantra that's tied to their birthday, so that we have, all the mantras end up being done in relatively equal distribution, so that the kind of meta-mantra will still happen on a planetary level, and they'll start to see the changes in their lives, and slowly then discover yoga and proper action and all this other stuff."

0:19:25 DR: They're not all gonna turn into David Lynch, but they'll all be improved. Similarly, here's the ancient rituals and technologies of being able to identify psychoactive substances and do them in a ritualized context and all. Funny, I originally, first when I looked at microdosing, I kinda poo-pooed it because it wasn't enough of a retrieval. It's like I don't want people to just use psychedelic chemicals as ways of optimizing their productivity that it's like Prozac or Lexapro or something. That it's just like...

0:20:11 PA: It's a buffer against the poisonous toxicity of modern culture.

0:20:15 DR: Yeah.

0:20:16 PA: It comes across...

0:20:16 DR: Yeah, which is an important thing. But having tried it, I can say that right, well, it's not psychedelic in the traditional sense, but it's medicinal. It's in the mix. It's... Even if it's not a gateway for genuine tripping for these people, it's funny. For me, it not being a gateway is a really good thing. If someone said, "Oh, my God, that's a gateway dude to stronger things." Oh good. It's like... And I'm like, "Well, shucks." Even if it's not a gateway for all people to full-on psychedelic experiences, I do think it could help people be a little bit more porous and contemplative and help people establish rapport that they can't right now. I often talk about the...

0:21:14 PA: Help people to trust a little bit more.

0:21:15 DR: Yeah.

0:21:16 PA: Yeah. Feel safe, a little more secure, feel a little more grounded, a little bit more in their presence.

0:21:20 DR: To discover eye contact.

0:21:21 PA: Yeah.

0:21:21 DR: And things like that.

0:21:22 PA: Yeah. Yeah.

0:21:23 DR: And that I've really seen with a lot of people. And in a way that's less... And nothing against any drug that people take, but it seems to be a little bit less jittery and brittle than the SSRIs that people take in order to get some of the same effects. It seems a little broader spectrum and...

0:21:44 PA: More holistic and... Well, even the research that they've done and showed what's the difference between SSRIs and psychedelics, oftentimes, SSRIs numb us to what we're going through and what we're experiencing, so they create this film between us and reality. Whereas what microdosing does is, from my understanding, it just allows you to go a little bit deeper into the mystery of reality. It allows you to to tap into understandings that you wouldn't normally be aware of or have the the ability to see.

0:22:14 DR: Right.

0:22:14 PA: Because you're just a little more open, you're a little more receptive. It is, in some ways, at least looking at it from a archetypal masculine feminine perspective, it's helping men, in particular, from what I've seen integrate a little bit more femininity.

0:22:30 DR: Yeah.

0:22:30 PA: And presence, and softness, and emotionality into them.

0:22:32 DR: And it's funny. And that's why, you were first talking about the the earlier psychedelics revival. What happened, we were in that kind of Eisenhower stiff 1950-60s world. It wasn't black and white, but it was early Cold War polarized confusion and men in suits and women in the home. And there's a lot of social control going on really since the FDR's time. Once they...

0:23:00 PA: And there needed to be for the World War and for all the stuff that was going on in the Great Depression and...

0:23:05 DR: Yeah. The social control, they started to do when veterans came back from World War II 'cause they knew these guys would be all traumatized so they built Levittown and communities for these folks. And they were really concerned and so they kept everything kind of in-line. And then we needed at that point in the heat of the Cold War and early American mass production and stuff, we kinda needed something to break that open. And that's why I looked at these things as medicines. They brought medicine to help break through that and we got peace movements, civil rights movement, environmentalist movement, feminist movement. I don't wanna say it was all caused by psychedelics, but it all went hand in hand with the medicines that were being taken to help loosen people's understanding of reality and it helps kind of break down some of the ideologies that had really replaced everything. We were living for ideologies.

0:24:05 DR: And then, now that we're in the height of another industrial age, this silicon computer chip programmed reality where people really wanna be machines, where we want to auto-tune the human voice, to fit the quantized notes rather than hearing the human being reaching for the note. It's like everything human is considered noise. What I'm saying and what I think psychedelics say, "No. No. That stuff's the signal." [chuckle] That's the stuff. It's all the liminal. Everything in between the ticks of the clock is where your life actually happens.

0:24:45 PA: Back to the mystery, and back to the unknown, and back to the awe, and back to the things that we can't quite quantify. 'Cause then when you quantify them, when you all make everything tangible.

0:24:54 DR: You're ground it. You lose the life. Basically, it's like turning biology into chemistry, or chemistry into physics. You lose the paradox. Life is a paradox. Life is fighting entropy. Why? And when you treat life as just the atoms, you lose what I think is actually animating this whole experience.

0:25:20 PA: Which is God or source.

0:25:23 DR: Or soul or something.

0:25:25 PA: Or soul.

0:25:26 DR: Something.

0:25:27 PA: Or something beyond our cognitive capacity and understanding of...

0:25:31 DR: Well, maybe. I don't know if it's... It's beyond the early scientific method to explain. It's not something you can do in-vitro. It's not something that you can break down into repeatable causes and effects. It's... When Francis Bacon says that science is going to subjugate nature, what are you subjugating? Yeah, it's wrestling her to the ground so she can be controlled, but then what would she have done if you hadn't controlled her? What was she thinking? And that's the part that they're trying to pretend doesn't exist.

0:26:13 PA: And that's the part that's now coming back to bite us.

0:26:16 DR: Yeah, between psychedelics with Jim Lovelock and the Gaia hypothesis. And whether it's Bohm and the Implicate Order, a lot of people even see it in a new science without even going as far as Rupert Sheldrake. You can still... You see it and these folks are not... They're not shy about admitting their... Well, not anymore, some of the psychedelic origins of what they did, from Ralph Abraham the mathematician, and there's a ton.

0:26:48 PA: Buckminster Fuller is another one.

0:26:50 DR: Yeah.

0:26:50 PA: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

0:26:51 DR: Yeah. And all the stuff that went on with Willis Harman at Stanford Research Institute or... These were all in psychedelics-influenced visions. It goes beyond that, is the thing. It's not that psychedelics are... They're not the subject either. They're just another tool. Another medicine for breaking certain things down. It's just that people will do... They'll do coffee, or sugar, or alcohol without a thought, something that's much healthier to look at. "Oh, gonna be careful with that." And in some ways, you do have to be careful with it because these are powerful experiences, especially if you're gonna drink a bowl of Ayahuasca or something. That's big, or do your DMT. But the kinds of simple mushrooms that cavemen and whatever. You're not supposed to call them cavemen anymore. That's another...

0:27:44 PA: Paleolithic ancestors.

0:27:45 DR: Paleolithic ancestors, yeah, would just walk around eat. Now it's a whole big thing. We don't have a balanced diet.

0:27:55 PA: Nowadays.

0:27:55 DR: Yeah.

0:27:56 PA: We haven't had a balanced diet for many, many, many years.

0:28:01 DR: Since probably... Almost since we went sedentary.

0:28:03 PA: Exactly.

0:28:04 DR: Yeah.

0:28:04 PA: Yeah. Well, and this gets... This is one of the fascinating things to me about psychedelics, is it again gets to this bifurcation that's developing between team human and the more AI data-driven futuristic approach. And it seems like the more that we can maintain relationships with things from our deep evolutionary history, these things that have made us human over the past 50 to 100,000, to 150,000 years, the more we can carry that ancient wisdom and tradition with us as we face these... This will be a really chaotic period that we're coming to. And then psychedelics, from my perspective, are the cherry on top. You have diet, you have sleep, you have fitness, you have these physical things that are great to pay attention to based on this ancient lineage and wisdom. But then psychedelics, they cross that whole... They're physical, they're emotional, they're mental, they're also spiritual. They really dial into all the humanness that we have within us.

0:29:12 DR: Yeah, it's funny. Even sleep. I was like... I feel like people have surrendered their sleep to Netflix. It's almost like, "Okay, you guys, you dream for me." And they don't get enough REM. They don't get enough anything. They're sleeping six, seven hours tops. And you kind of need eight. I guess unless you do some Tim Ferriss thing at night, you're allowed to optimize it, God bless, do what you can.

0:29:37 PA: Sleep for 20 minutes every two hours or something.

0:29:39 DR: Yeah, and I'm sure there's ways you can hack that thing as long as you get your REM. But we don't get to sleep. And we don't get eye contact, we don't get rapport with other people. We have our conversations on Skype or on smartphones. And when we're with each other, we're not making eye contact, we're on our devices and multitasking. And we end up incapable of bonding with other people. If you don't make eye contact, the mirror neurons don't flash. You don't see if the pupil is getting bigger or smaller. The oxytocin doesn't go through the blood and you don't get bonding, you just get distrust after every interaction. So how are we gonna forge the solidarity we need to confront our problems if we don't have the basic ability to establish rapport with other people? So the extent to which a different diet or different chemicals and different plants are going to engender the trust and patience to do that, it's what we need. I got... I teach at CUNY now. And every semester, I had more students coming up with a note on the first day at class. "Please excuse Johnny from class participation and group projects, he has social anxiety."

0:30:51 PA: And he just can't handle it, can't deal with it.

0:30:55 DR: Yeah. And I look at that and I think, "Well, what happened to this kid K-12?" He was probably sitting on an iPad and doing solo exercises. They didn't treat the classroom as this sacred space for young people to interact with the teacher. Teachers are probably scared of them or whatever, and that's a problem. Basic social skills are kind of...

0:31:19 PA: Necessary, we can say. And these are the things that even I wasn't taught. These are the things that I had to learn on my own. When you're growing up in middle school, in high school, it's not like you're taking classes on connection. And it's more, it's math, it's science, it's... There's a lot of things in our current educational system that are just not communicated well and understood well. It's very much within that industrious... Still our educational system is very much a product of the early 20th century.

0:31:50 DR: Yeah, and then the mid. It was... When the Russians launched Sputnik, the American education system went, "Oh, shit." And that's when they added calculus and all the science so that we could compete. And in some ways, it was a good thing. For at least a while, we owned computer technology and all that stuff, and the game and entertainment industries, but now we're falling behind. And I don't just think it's because we're not teaching enough STEM in our high schools. I think it's because we're so depressed and mentally ill, and incapable of collaborating, and have no values and things like that.

0:32:33 PA: And how did we get to this point? What led to this... From your perspective, what led to this mess, this existential crisis that we're now going through is as a Western culture?

0:32:44 DR: I think it's mainly that we discovered that people... The more you individuate people, the more stuff they buy.

0:32:52 PA: This is like Edward Bernays and the manipulation of modern marketing to create insecurities so we can sell people more shit.

0:33:00 DR: Right. And it was based on an economic model that requires growth. So if on your block, your block chips in and buy one or two lawn mowers that everybody uses, that's great for the people and their friends and they're sharing, it's good for the environment, but it's bad for the lawn mower company. Lawn mower company needs to sell more lawn mowers this year than last year. How are they gonna do that? By making sure people don't borrow each other's lawn mowers. So we have an economy that requires de-socialization in order to grow. Everyone needs their own TV, their own this, their own that. Everyone needs to spend as much time alone as possible. And that's not a recipe for a successful culture.

0:33:50 PA: And this has been going on how long? Would you say the 20th century? Would you say it's been going on since the advent of industrialization?

0:33:57 DR: Yeah, Robert Putnam wrote a book called Bowling Alone. And he said that we kinda reached a peak of civic organizations in the early 1900s, like Kiwanis and Elks and all those rotary clubs and things, and boy scouts, and all that stuff happened. And then after World War II, it just started to diminish. So it was the advent of television and advertising.

0:34:22 PA: Which is what a lot of your work is focused on, the role of mass media. And that's really what you've built your career on, has been the critique of media and mass media.

0:34:32 DR: I guess so. For a couple of years, in 91, 92 it was about the excitement of the possibility of this internet-y interactive stuff to kind of reverse those decades of mass media manipulation. And then around 1994, I kinda went like, "We're going in the wrong direction here." If we leave Mondo 2000 behind and let Wired be our stewards for the digital revolution, it's gonna go bad. We're gonna end up... It's gonna be about business and the long boom and selling more things to more people rather than connecting civilization and being the neural realization of the Gaia hypothesis, which sounds a little incredible and pollyannaish, but I still think that's the role of these technologies. That's the role of media, is to connect us. When it connects us, it's doing a great job. When it disconnects us, it's working against what I think is the human and nature's agenda.

0:35:49 PA: Is there anything that could be done? From your perspective, are you optimistic about the future in a way? Are you optimistic about things like blockchain and these "new emerging technologies" that are supposedly gonna overcome all the downsides of the internet that has been the case? Or there's just gonna be more second and third order consequences that we just don't anticipate and see?

0:36:14 DR: Well, I'm not optimistic about technology's ability to solve technology's problems. I don't know that another layer is gonna help. That said, there's good people doing good things, Art Brock and his Holochain, is a decentralized blockchain idea which is more true to some of those original nature-based visions of networking technology. There's folks... When I sit with Charles Eisenstein and other folks, I get a little happier. I just went to this conference that he was at with all these really rich people in banking and finance and stuff, who really wanna flip it, who wanna do the right thing and inviting indigenous peoples to come and figure out what the hell do we do now. And sometimes I think, "Oh, cool."

0:37:23 DR: When they all say things like, "Well, yeah, we just have to make sure there's good return on this." And that's when I'm like, "Oh, maybe that's not gonna quite work." Or when I look at our climate situation, I get concerned that unless Earth itself has a few Trump cards that she hasn't played, which she probably does, just they might not be pretty ones, like rainforest diseases and ways to reduce human population, it looks kinda scary. Two degrees is not good. There's already millions of people in India that have to leave where they are to get to places that aren't this hot. It's like the human body can't survive at certain temperatures. So I get not concerned for life on planet Earth, but I get concerned for, you know, this civilization might have run its course.

0:38:29 PA: And then AI will replace us?

0:38:31 DR: Nah. No. I don't think they'll be able to keep AIs around without people. And they can't replace us. AIs can go do things, but I don't think they'll ever be aware of themselves. I don't think they'll be us. I don't think they'll have souls. But then there... That's non-logical religious talk. But yeah, that was the original inspiration for the whole Team Human thing I've been on, was this argument I got in with one of those singularity guys who was saying that, "Humans should accept their inevitable extinction and replacement by our robot overlords." And I made an impassioned argument for humans that we can embrace paradox and that we're special. And he said, "Oh, Rushkoff you're just saying that 'cause you're a human. It's hubris." And that's when I said, "Fine. I'm on Team Human, Team Human. [laughter] Guilty. Guilty. And if when the AIs are in power, they'll see my writing and know that, alright, I'm one of the ones they should kill." 'Cause I still think humans have this...

0:39:44 PA: Hopefully, it never gets to that, right? Hopefully, the AI and the robots that come to be are...

0:39:50 DR: Our friends.

0:39:51 PA: Benevolent and friendly, and there's a relationship there. And I think that's also something that came for me when I was reading your work, it's like, "What's the difference between the cyborgs that we currently have?" So the Neil Harbisson. You know Neil? He has that big antenna that comes out the back of his head.

0:40:09 DR: Oh, yeah.

0:40:11 PA: He's given a couple TED Talks and he speaks about that. He's kinda like this form of cyborg, that's going around and talking about how he now has this implant and he can sense things with it and what that means for the future of humanity once we start basically grafting pieces of machine into our skull, essentially is what he's done. But he still is very human or seems to be very human. So it's also, what's the distinction? Where's the difference between what humanity consists of and what...

0:40:43 DR: I don't know, it's kinda like with drugs. I did all sorts of drugs, but I never injected anything. It was like somehow breaking the skin barrier sort of felt like that'd be pushing it. That's... It's almost like your body and neurology calibrate themselves in extremely complex ways, I don't even mean complicated, I mean complex ways like fractal complex ways, to time and light and other people. And I think that we interfere with those calibration mechanisms at our own peril. It's bad enough that we live in cities with grid patterns, that we have electric lights at night to keep our pupils small or whatever so we can read, and televisions and movies with flickering images that we put together with our minds and... There are beautiful things, but they're also challenging our basic coherence as organisms.

0:42:14 DR: If I have students who can't make eye contact, but they can look at Instagram, and then you look at works of guys like Bill Softky, he's a guy I've had on my show, who does a lot of work on neurochemical mechanisms for trust and peace of mind, and how easily they get thrown off kilter by screen experiences. You realize, "Wow, we're walking around in a decalibrated state." And the things that we could use to calibrate are, they're around. Nature helps calibrate, the ocean helps calibrate, being with a person, breathing, forming rapport, fucking. I mean there's a lot of ways that you kinda recalibrate your nervous system. And I get concerned about interfering even more than we already have. I don't even like having a cellphone around, you know, just fear of what, I don't know what the little waves are doing to me.

0:43:17 PA: Fuck it up here. Well, there's this thing, if you hold it in your pocket too long is it messing with your...

0:43:23 DR: I know. It messes with your sperms.

0:43:25 PA: Yeah, your sexual potency. I was just talking with a friend yesterday. I'm like, "At this point I feel like I don't really have free will or agency or autonomy, that there's an element of... Because I'm on stuff like Instagram and Facebook and email and I have a phone, that I've given up a lot of that agency and autonomy to these technological overlords that we now have, which is basically Apple, Facebook, Google, and Amazon."

0:43:52 DR: Yeah.

0:43:53 PA: The big four.

0:43:53 DR: Well, and then also I mean, this is what I'm wrestling with. I live a life where my livelihood is dependent on producing thought at the rate of the net. So now I write for Medium and they kinda want me doing a piece a week, a little piece a week or a big piece every two weeks. And if I'm doing that and answering the email and doing my little Skype talks and then it's like, it is my... It has become my leash. And if it's not the technology itself, it's what comes... All the voices and things that come through it. And I'm wondering, "Gosh, if I just let all that go and just started just teaching my classes and doing theater. What would that be like?" It's almost a utopian vision at this point. For me, and I guess partly it's because I feel I'm... It's just neurosis, or I'm operating at some deficit, or I owe something to everybody. I answer every email that comes in, and it's hundreds a day. And most of them are from people, "Can we just hop on the phone for 20 minutes and I can tell you about my blah, blah, blah? Give me some feedback, so I could pick your brain about where to go and what to do." And I feel like an asshole if I don't try to make time for everybody, but then I'm looking at myself right now with this sinus infection, exhaustion. I'm run ragged.

0:45:47 PA: Well, this has been going on for a while 'cause even when we were exchanging emails like a month ago, I got the sense that you were tired and like going through a lot.

0:45:57 DR: It's been going on like this for maybe five or 10 years. But in the last year or so, my stuff from like 10 years ago is finally like, "Oh, okay. He's not an asshole. He's right." I wrote this book Life Inc in 2006 or 2007, saying, "A mortgage crisis was gonna happen, the economy is not working, there's too much growth, here's why it doesn't work." And Wall Street Journal and everybody just ridiculed it, laughed, "And this guy's a fucking conspiracy theorist, insane." Or they're thinking I'm misreading Adam Smith. And it's like, "They haven't read Adam Smith. Adam Smith was a moral philosopher. He was a fan of small business and little towns and anti-corporate. And he was one of us, not one of them." I mean, then they ridiculed that stuff. And now, finally, it's like now I'm invited to Bretton Woods to talk to Larry Summers and Peter Theo about where the economy went wrong. And now, they finally see, "Oh, okay," which is great. But what that also means is I get hedge funds emailing me.

0:47:04 DR: People who run hedge funds like these kind of mutual funds for the rich and famous and they invest in different things, emailing me saying, "We wanna create a sustainable hedge fund. Will you tell us what to do?" And me, the sucker, I'll go and do the lunch and tell them what to do and then they'll go make a zillion dollars doing some Doughnut Economics Lite and like fake indigenous investing or whatever. They'll do some watered-down version of what I've told them and make a zillion dollars, and it's like... And I feel, I'm obligated to meet with them because I'm trying to convince them to do social good, and if I have access to this wealthy person then, of course, I have to. But my own life is gone as a result. I'm just becoming this...

0:47:58 PA: Do you feel like it's sacrificial to some degree, and there's purpose in that and meaning in that sacrifice? Or do you feel like it's all for naught? So to say that it just seems like wasted energy that it's at this point hopeless or whatever it might be.

0:48:17 DR: I don't know. When you talk to a...

0:48:18 PA: Or both. For me, I'm like sometimes I'm both. I'm like...

0:48:23 DR: You talk to a healer or someone who does Reiki and all that. And they don't get tired doing it, and their belief is if they do get tired or exhausted doing it, it means they're not doing it right. They're not Aikido-ing the energy of it. They're taking on... If you're taking on all the poison energy, then that's not the right way to be doing it. Or like a therapist, I'm sure they get tired, but they don't catch your neurosis when you talk to them. They've got some way. They don't do so much countertransference that they go home crying. You know, I couldn't do it, but... So no, I think it means, not that it's for naught, but I'm not doing it right. Or it's okay for me to say, "I'm so glad you've discovered that you should take the time and read this book. If you really wanna meet with me, you can hire me for you know what? $10,000 a day, right?" Some crazy thing 'cause they're billionaires. What am I going over and having lunch with a billionaire for him to become more of a billionaire?

0:49:43 DR: I fool myself into thinking, "Oh, they've seen the light. They're coming to me 'cause they wanna... " No, I go to these things. I went to my last one. I won't even name it, but these things like assemblage-like things where they'll bring like 20 really wealthy people who've seen the light or had their first Ayahuasca experience. Bring them together with five or 10 of kind of you or me, and wanna have an experience that will help them figure out how to heal the planet together. So they wanna be the new leaders of humanity's return to wisdom. And they're hoping that some kind of an Esalen Omega Institute experience is the thing that will heal the planet, right? So they will go and they'll be like a Qigong master and an herbalist and special healing things and ringing of bells and all that great, feel-good stuff. But it's like, "Sure, do that on your own time. Pay for that and get your sauna rub or whatever your thing and your ionizer, but then just join Extinction Rebellion, join Sunrise." There's enough... You shouldn't... You're the leaders of the thing that fucked us up. There's new leaders now. Talk, contribute to AOC. Get the Green New Deal going. It's like, it's not a blockchain or a hedge fund that's gonna fix this. It's all hands on deck shift in how we do what we do.

0:51:46 DR: And radical change is gonna mean radical change. You can't just take all that money and then somehow shove it back in the system. You took too much to begin with. Mark Zuckerberg wants to give back 90% of his money or his stock. Why didn't you... If you're gonna do that, then why not just not have made Facebook into an extractive, horrible nightmare?

0:52:13 PA: Incentives, yeah. What are your incentives? What are your values? What drives you? And this is where it gets in, to me, into the plant medicine and the psychedelics. It's like if done in a "proper context" or ceremony or with elders or with... Where there's a lineage involved, there's an element of... These experiences can be rooted in compassion and kindness and love for the other and love for community and love for the Earth. But oftentimes, when you just drop them in for some of these higher-end people, then a lot of the old values still are there, they're just now figuring out how to work the system a lot better because they now have these tools that, frankly, are very insightful and useful. So it's almost like... Who's getting access to these? And is it actually gonna change the world like we think it is? That's one big thing that I worry about 'cause for me, it's like the work with psychedelics, it's like... It's kind of my last hope, in a way, you know?

0:53:20 DR: It's not gonna do it. Unfortunately, it would have done it the last time. It's not gonna do it because... I thought, when I had psychedelic experience in college, "Anyone who has this is gonna be enlightened and fine, this is it." And that's why, Leary and Hitchcock... What was her name? Patty, Peggy Hitchcock, something, got LSD to JFK. Figured, "Okay, he'll do it. And then, once the president's done it, then the world can all be fine." But you could do psychedelics and still be a total asshole and still... As we've seen... And still be a total womanizer. And still fall prey to the temptations of the flesh or the temptations of money. I would do psychedelics and go to the parking lot of the Grateful Dead show and be with a burning-man-level sense of community and support and... There's a new society here and it's all good.

0:54:32 DR: But you could also go and see kids in the AC/DC parking lot doing LSD. And smashing beer bottles and screaming and smashing cars into to each other. And I was like, "Wait a minute, they're on acid? And they're doing this? So... And that's when it goes back to Tim Leary, and it's your set and your setting. What are you bringing to it and where are you doing it? And if what you're bringing to it is young hormonally insane young male teen energy to it, you're gonna have that experience. So it's not... It can't intrinsically change anything, but the work you're doing is interesting. I'm interested to see if low-dose psychedelics give people a little bit more resilience, kinda make people less brittle, so it gives them... It almost sounds like CBT, like cognitive behavioral therapy. What if it just gives them time to make a different choice in a particular situation?

0:55:49 PA: To be more responsive than reactive, is the word.

0:55:50 DR: Right. Right. And that's what it would be... For me, it would be like... Well, what if I go to my computer in the morning. There's the 300 emails. What are other approaches I could take then? Oh, it's like Robert Anton Wilson would say, "Oh Doug, you're in a reality tunnel where you are thinking that you owe everyone of these people something, and that if you don't give them what you owe them, they're gonna be mad at you. Why are you in that reality tunnel Doug? What's... Maybe you wanna find out... "

0:56:25 PA: Why are you in that reality tunnel, Doug? You know, right?

[laughter]

0:56:30 DR: Oh why? Exactly... Well, I could play Freudian. I'd say, "Oh, 'cause I was with a mother who was emotionally needy and I had to stay aware of her emotional state at any moment and give her what she wanted in order for her to nurture me the way I needed." So it's like, "Well, wait a minute, those people are not your mother. They're something else and they may be nice, they may not be nice. But even if they're nice, it doesn't mean that you owe them your time." I don't know. What do you do? You probably get more than I do at this point 'cause you're known as the microdose guy. I'm sure that thousands of people who are thinking about microdosing all want to ask you their individual questions.

0:57:09 PA: Well, that's why I wrote the course. So I'm like, "If you wanna learn about microdosing go... We have these resources, we have this course." So it's almost like, what can be done to take knowledge and information to build systems and processes around it and then to deliver it in a way that people will learn from and basically like... How can I, not clone myself, because that's a little... But clone myself. Take the knowledge of information, and in some ways you've done that.

0:57:35 DR: You're not cloning yourself, you're cloning the data.

0:57:37 PA: Right. Right, right, right. And I'm making it more accessible and I'm making it so it's not dependent on my time and energy, so it's not just a single...

0:57:44 DR: That's why people used to write books. That was the whole point.

0:57:47 PA: Exactly. And you've written a lot of books.

0:58:34 DR: And my problem is, I write the... And I thought it would work like that, but what actually happens is: People hear about a book and then email me for the question that they want answered so they don't have to read the book. I mean, in some ways, that's how I have a speaking career 'cause nobody wants to read it. Just give us a 30 minutes that apply to us. Curate what you're doing for us, so we don't have to. So, writing the books doesn't serve its original function of distributing my ideas to many different people at the same time. All it does is serves as an invitation for people to email me questions about something they don't wanna read.

0:58:35 DR: Podcasts on the other hand, people actually seem... They'll take the hour and listen to it. Or these articles I write for Medium 1000-2000 words, they'll read that. So this book, you know, Team Human sold, I don't know, 20,000 copies, maybe it's sold another 20,000 audio books. The single little article I wrote that was kind of for the ideas of Team Human for Medium, about these billionaires who you know were building their bunkers, and how that's this anti-human sentiment about the future. That's gotten several million real reads. Okay, so that's how you reach a couple of million people is with 1000 or 2000 words.

0:59:16 PA: Shorter bits of information. Yeah.

0:59:18 DR: Yeah.

0:59:18 PA: Yeah, yeah.

0:59:19 DR: And locking myself up for a year to write a book that then comes out a year or two later is not maybe the cycle that I wanna be on right now.

0:59:30 PA: Instead just... But then in some ways you're giving in...

0:59:38 DR: To the digital...

0:59:39 PA: To the digital...

0:59:40 DR: Short-form...

0:59:40 PA: Short form... In a way, so you're being adapted to this maladaptive system. You're being adapted to this anti-human system.

0:59:47 DR: Yeah, but there's ways to be human in there. In other words, the book is not the only form, but that's part of why I wanna go do theater, you know, 'cause theater... If I'm doing a play that's... Doing a play is not an invitation for an email question. Doing a play, people accept that, "Oh okay, that's something I have to go experience." So no one's gonna write, "Oh, Manuel-Lin Miranda, whatever, so tell me how do you end the first act of Hamilton?" Just go watch the fucking play.

1:00:27 PA: Yeah, we're not gonna tell you that shit.

1:00:29 DR: Do you know what I mean?

1:00:29 PA: That's not gonna happen.

1:00:30 DR: How do I end the act? Just go watch it. You know, it's... People accept that and people don't... Because books have been so... Books were sacraments to me, books were experiences. People... Everybody writes books now and they think of books as just 200 or 300 pages of information. It's not, a book is a experience. You go in the mouth of it. A book is an acid trip. A book, as I see it, a book is me taking your hand and walking you through the darkest fucking place I can, and then bringing you out.

1:01:01 PA: And inspiring you to like go change it. That's why I loved the last line of Team Human, which I won't share.

1:01:08 DR: You can. Find the others.

[chuckle]

1:01:10 DR: Find the others. You know, it's... They're out there, we're out there. Yeah, and that's why... You know, I like Team Human also, I like it as a last book because it's kind of a mic drop. You know, it's not a book about something, it's a book that is this experience. Go through this and rediscover your humanity, the enemies to your humanity and how to connect with other people, which is the only way really to retrieve humanity. Humans are a social phenomenon, we are a team sport. And that's sort of the thesis of the book, and that anything that keeps us from each other is the problem, is the enemy. So if you start evaluating the things in your life that way, you know what is bringing me together with others and what is just lumping me in an affinity group, it's not really connection that's just branding or something.

1:02:08 DR: And then, all these devices, are they really helping, are they helping me connect? If they're helping me make an appointment to actually find a person, you know... And that was the premise of Meetup was... And it's funny, 'cause Meetup... He came up with Meetup, Scott Heiferman...

1:02:26 PA: You're in the board of Meetup?

1:02:27 DR: Yeah, I was. Now, they're bought by WeWork, so it's kind of gone. But we lasted 10 or 15 years. You know, and the idea came after I gave this talk at Disinfo Con. It was Disinformation had this convention in like 1999 or 2000. And I gave the talk, Find The Others, which was originally a Leary quote, of way he responded to a girl who said, "I had the acid trip. I've seen how everything's connected, what do I do now?" And he said, "Find the others." So I gave that Find The Others kind of talk that the point of the Internet shouldn't be to engage with people online, it should be to find the others and then you engage with them in real life. And he was like, "Oh, I can make a platform for that." So instead of people finding each other and staying in a Yahoo group, you find each other and then go meet in real life.

1:03:11 PA: So you were the inspiration for meetup.com, that talk.

1:03:13 DR: In part, yeah.

1:03:14 PA: Oh, that's so cool. I didn't know.

1:03:15 DR: It was nice.

1:03:15 PA: That's really cool, yeah.

1:03:17 DR: Yeah, and he meant it. I mean, it was just hard to keep it going. It was a sustainable business, but not one that was gonna grow into a multi-billion dollar thing.

1:03:30 PA: Well, and this is something that I have come back to. It's like how do you measure this new form of wealth. Like going beyond financial wealth, but really like social wealth and community wealth. And like how do we define social capital, how do we define ecological capital, even those terms themselves are difficult, because they're being fit into like an old paradigm in an old system. So how would you define social capital? How do we put more definitions around this concept of social well-being even though the way that most people understand is money in the bank, and an apartment, and...

1:04:08 DR: Well, once you find a metric for it, you're gonna be reducing it to something icky. Actually it has to be... Certainly, for any of us, meaning Westerners with the ability to listen to podcasts, it has to be experiential. And that's scary for people too. But moving more towards that kind of 360-degree understanding of wellness, and connection, and rather than this... I don't know, the net really imposes a state of panic and desperation. And even just touching it, I always feel it's strange. I mean, I remember when that flipped and that was back in the '90s when I used to get done with email and feel invigorated. Now email is just like this drain. Because it's because we can't help it, we abuse it, people abuse it, they... The bias of email is to create greater access to you and... Gosh, we all need work, we're all freelancers, we all need the opportunities. So email is so much about, is there... Does one of these have a job in it? Does one of these have an opportunity? And that's not fair either.

1:05:51 PA: Trying to find the needle in the haystack, so to say. Yeah.

1:05:54 DR: Yeah, or is there gonna be someone who has something that's really gonna change my life, and is that gonna come through email rather than from someone I just run into? And all the filtering that goes on between who gets through versus there's something you coulda learned from that person at the bus stop that was in your normal path. That's the whole thing with technology. Kevin Kelly explains it pretty well. The technology gives us choices, more and more choices. And at a certain point, do you wanna be making all those choices all the time? Choice can tend toward the more Yang side of things, active choice versus passive reception of what's coming through.

1:06:49 PA: The more feminine.

1:06:50 DR: Yeah, I mean, at least are archetypally, yeah. So, we'll see.

1:07:00 PA: We'll see.

1:07:00 DR: You know, I mean, I know I'm not a microcosm for the planet, but sometimes I feel like it. There is something to be said for... I got in this argument with a... Team Human-y argument with an environmentalist, this young woman in Europe who was telling me why should we protect the humans? The humans destroyed their Brazilian rainforest, which is basically the lungs of the planet. And maybe humans are the problem. And while she's talking to me, she's smoking these Gitane, or whatever, Gauloises cigarettes, and I'm like, "Look, maybe you should protect your own lungs before talking about the lungs of the planet." All is one in the great fractal of life and...

1:07:53 PA: Did she like that?

1:07:54 DR: No.

[laughter]

1:07:54 DR: She thought I was doing the thing... And I understand, calling out individual hypocrisy, so it's like, "Okay, I flew in a plane to Europe to talk about climate. Is that appropriate or not?" And it's like, "No, it's not appropriate but it's a compromise." Just smoking fucking cigarettes though as your entertainment, it's like that's not some necessary compromise to something. I think it's just... I think it may be just bad.

1:08:23 PA: Yeah. Yeah, it is.

1:08:26 DR: Maybe the way Native Americans did it, once a week...

1:08:30 PA: Ritually, as a medicine, it wasn't what the industrial world has now made cigarettes.

1:08:36 DR: I don't think they were chaining.

1:08:37 PA: These little addictive things to keep you distracted and numbed to the emotional pain that you're actually going through or whatever it might be.

1:08:43 DR: Right. And that's, of course, the danger that you hear about micro dosing, is it a way of taking Earth Mother and divvying her out, [laughter] so that people can have the good without the change? But I would argue that hopefully not. Hopefully, it's not just safer speed but a... And from the evidence so far it seems it's equipping people.

1:09:15 PA: Well, is a lot about the educational process. That's for me the key thing that I'm always focused on is how do you teach. And a huge part of teaching and a huge part of learning is experiential. So it's one thing to read Michael Pollan's book and go, "Oh, psychedelics do this and psychedelics do that." It's another thing to actually like, at least, especially for a first time person who's in their 50s or 60s whose never had a psychedelic experience before to like surrender to that level of unknown when they have already so much stability and structure, so they're gonna go do 6 grams of... Or 5 grams of dried Psilocybin mushrooms in the dark and just jump right in off the bat? Probably not. In some ways, they might be more likely to start with a microdose and go, "Oh, okay, this is not near as chaotic and crazy as I thought it would be. Now, maybe I can go a little bit deeper, and a little bit deeper, and a little bit deeper."

1:10:08 DR: I wonder though, do we have actual evidence that older people with more formed egos and all whatever, that they have a rougher time with a major psychedelic experience than a young person? 'Cause my subjective experience, I hadn't done psychedelic in a super long time.

1:10:29 DR: Hadn't and then did. And I was worried that okay, after 10 whatever years or 15 years of not doing this, this is gonna be really rough or whatever. And the thing I realized instead was that over the course of my life, having faced the real demons, sitting with my mom as she died, and my dad as he died, a bunch of those things, car accidents and deep questionings about everything from my right to live, and my sexuality, and my quality, and my marriage, and bringing another life into the world. I've been in the darkest, darkest places that drop five hits of acid and it's like, "What are you gonna show me that I haven't already stared in the dark maw?" And maybe it's just having a good setting, but these chemicals aren't gonna show me anything darker than I've already stared at. All they're gonna do is give me the context to see where they came from and how... They're gonna bring them to me in a gentler, more loving, more holistic full spectrum way than I already bring them to myself, you know what I mean? I'm already in the bad trip here.

[chuckle]

1:12:09 PA: The pain and survival.

1:12:11 DR: Yeah. And seeing and once you understand the... It's almost like the old coyote legends. Once you understand the pain and suffering that you cause with every step that you take... What it means to eat, what it means to live, it sometimes makes me wonder, but I guess it also has to be someone who moves through life a little bit consciously, that did stare in the face of those things and didn't just...

1:12:35 PA: Well I think a lot of us as humans have gone through that. And I think that that point is very relevant that people in their 50s and 60s, they've gone through these experiences. Most don't have the context that you do, of understanding then, that actually a psychedelic is not gonna be any more difficult than some of these things that they've already faced in life. There is this element of because it's so stigmatized and because there's so much poor information out there, that they think, they really genuinely believe that it is this terrible or potentially... They're gonna lose their religion as a result and that they're gonna lose whatever X, Y, and Z might be as a result of this.

1:13:08 DR: And that's 'cause there were these acid casualties in the 60s, occasionally, someone would jump out of the window or Art Linkletter's daughter or something.

1:13:17 PA: People would jump out of the window, or... Yeah that was it.

1:13:19 DR: That was the big story.

1:13:20 PA: That was it.

1:13:26 DR: Yeah.

1:13:26 PA: So, why did you take so much time off of psychedelic? We haven't really talked about this at all. What's your relationship like with psychedelics? How did they first come into your life? And then it sounds like recently you've re-explored a little bit?

1:13:39 DR: In college, I went to Princeton in the height of the new Republican era, when...

1:13:45 PA: This is like early 80s?

1:13:48 DR: Yeah, yeah, early 80s, when Reagan. End of Reagan and, and...

1:13:54 PA: George HW And...

1:13:56 DR: Yeah, like Iran-Contra kind of time. And there was like 12 of us at Princeton, who were radicalized by this awful thing that was going on in America...

1:14:16 PA: Which was the Reagan Presidency or the Iran-Contra Affair?

1:14:19 DR: Yeah, it was both, it was Reagan.

1:14:20 PA: All the things...

1:14:21 DR: The sorta yuppie scum, everyone thought we'll just get rich. It was Gordon Gekko and Wall Street, and that was the new America. We'd won the Cold War, so all this people stuff is bullshit, community and all is bad, everyone just being a strident individual, get your money and go work for a bank. Everyone was graduating Princeton and going working for Morgan Stanley. I'm like, "Jeez, you just got educated, why be a stock broker? You can do anything." So there were like 12 of us. And so these guys lived in this house and they called it the Fourth World Center, which is kind of a thing. And they would do these parties where each room would have a different brain, ambient playing in it. And they'd have drugs, they knew some guy at Columbia who was making acid called "Golden Dolphins" and we would do that and have these... I remember I had my first trip was with Walter Kern, who's a novelist, and we just walked around the campus and saw the whole thing.

1:15:26 DR: And then went to the psychology library and found... Which they had at the Princeton psychology library, they had Timothy Leary's Tibetan Book of the Dead psychedelic manual and read that. And there was just no mentors, there was no tutelage. All you could do, 'cause we were a discontinuous little blob of 19-year-olds discovering these substances and then using the books to find out what to do. So there's True Hallucinations, or what, Imaginary Landscape, I guess, was the counter book. And there was some of the early Leary stuff and then just kind of wing it... And then that... The internet happened which seemed to be the, and was early on this sort of physical manifestation of the psychedelic urge of just growing this neural system, neural network and connecting with other people and breaking down boundaries and having no such thing as secrets and privacy.

1:16:26 PA: Open sourcing. Right.

1:16:27 DR: Open sourcing everything, which has turned into data mining. But it was a different kind of a thing, it was an experiment in intimacy. But, yeah, it went all business-y and then I just didn't... I kinda got the Alan Watts thing of once you get the message, hang up the phone. And I didn't really see... After I did some experiences with Leary before he died, in the mid-90s, 'cause by then, yeah, you're a friend of Leary and going to all the parties.

1:17:03 PA: And what was he like to hang out with then to spend time with him?

1:17:06 DR: He was actually, he was sweet, but he was really hard to hang out with because he had a kind of a dominant personality, and so being with him was a little bit like being with a very particular kind of acid, it has its shape and then you kinda have to conform to the shape or to the process that he's going through, which is kind of being in a certain kind of intellectual crucible. And being in his ego space, which he had and 'cause he's a guy born in the late '20s or something, he was a different...

1:17:51 PA: He was a fucking legend. It's Timothy Leary.

1:17:52 DR: Right. So he had a kind of a rock star thing. And so his world was a little bit not cultish really, but controlled. So it was great, but also... I didn't live there. Some kids just lived in the house, were there all the time. I would dip in two days and then come out because I was trying to maintain maybe my own ego, but also my own journey. It was about... I wanted to do my thing and not be a...

1:18:31 PA: Timothy Leary's accolade or...

1:18:33 DR: Yeah. Fanboy or something.

1:18:33 PA: Or fanboy or something like that.

1:18:33 DR: But yeah, it was fun. We explored lots of things and I put him in VR gear for the first time.

1:18:43 PA: Really?

1:18:44 DR: Which was fun. Yeah. And was there when he was first going on the World Wide Web. So those were early heady wonderful days. And then when he got sick, I was there to help with the... Really helping fund his death. So I got him a book deal with Harper Collins with my editor for a book called Design for Dying. Which he didn't end up writing but we got R. U. Sirius to write it at the end, based on a lot of his stuff. And I was trying to help almost be like almost a literary agent for him in some ways just to bring cash into the house to support the people trying to help him and to get nitrous tanks and whatever he needed. But no, he was a really interesting, positive intellectual example, both in what he did right and where he went maybe a little bit wrong. But after what he went through, being imprisoned in solitary confinement and all and dark stuff, and then...

1:19:53 PA: And escaped, and went to Algeria, and went to Afghanistan.

1:19:56 DR: And then being a prisoner to them. It's like for him to then get to LA and wanna live in a nice house and be friends with movie stars is like, come on, man, let him...

1:20:07 PA: Give him a break.

1:20:08 DR: Yeah, exactly.

1:20:08 PA: Yeah, let him live a little bit. Enjoy it.

1:20:11 DR: And the fact that he was always open to people's ideas and... He, in some ways, is a better listener than I am. People would just come to his house and they would ask him a question, he's like, "I don't wanna talk about me. What are you doing? Tell me. What do you think?" Just to try to... He would also dismiss people pretty quickly if they didn't have something, they weren't bringing something to the table. But he was just hungry for insights and had young people around all the time to know what's happening, what's new. But yeah, I liked him as a person. I got a thing at what, 12:30. As a person, I like Robert Anton Wilson. He was the one... When I met him, it was like there was just no pretense at all. He was just like... From the first minute I met him, it was like Uncle Bob.

1:21:08 PA: And can you explain just for our listeners who Robert Anton Wilson is just a little bit, a little content.

1:21:12 DR: He's a guy... He wrote... He was a friend of Leary. He's a little bit younger, I guess. And a 1960s Berkeley writer-thinker guy, big pot smoker, and he wrote for Playboy. But he was all into life extension and space migration, and how's the human organism changing. He's the guy that came up with the phrase "reality tunnels" that people live in. And he wrote these really bizarre conspiracy novels, like the Illuminatus Trilogy. That's him. And he had a writing partner for a lot of that, but I knew him.

1:21:51 DR: And so he was a scholar of James Joyce, and a user of psychedelics, and a thinker about how human beings are gonna change. And I did a reading for one of my first books, Siberia, up at Capitola Book Cafe near Santa Cruz. And he just showed up at the reading. A lot of people were there, like Ralph Abraham was there. I think Rudy Rucker was there, the whole Santa Cruz crowd. And here I am, and this 29-year-old kid or something, talking to my heroes. And he comes up after the reading is done, he says, "You wanna come over? Come over and have a beer or something." We'd walk... He lived in this garden apartment around the corner from Capitola Book Cafe and we'd just walk there, had a beer, tea or something and just like... It was just like... It was the closest to when I would do a reading in Miami or something and then go home with one of my great uncles who lives down there, go to their little condo and...

1:23:00 PA: Just hang out.

1:23:00 DR: Yeah.

1:23:00 PA: He's like family. It felt like that. He felt like he was family.

1:23:04 DR: Yeah, and the conversations we had were... It's almost hard to describe it. Rather than having a directly or immediately profound conversation about the fate of humanity and human evolution and the mind on psychedelics or the shape of ego, we would talk about totally mundane things, but with all of that behind it. It's kinda hard to describe. It's almost like a psychedelic conversation. "So how did you get over?" "Oh, well, you know, I flew to San Francisco and then I did one of the SuperShuttles to get here." And it's just all the...

1:23:51 PA: It's like the metaphor that lays on top of the...

1:23:53 DR: Yeah, exactly.

1:23:54 PA: The kind of existential depth underneath.

1:23:56 DR: Exactly. "What are you reading now? Yeah, I've been reading a Beckett novel I never read before." "Really?" "Yeah, you know, Beckett was... " Then he would say, "Beckett was Joyce's secretary for a while." So yeah. Then it's like, Okay, what have we just done? We've just made a generational comparison between Joyce and Beckett, and Robert Anton Wilson and me of... Or mentor relationship or literary touch stones. And it was just... But with no performance. It's like usually you meet one of your idols, and it's like you either feel compelled to perform for them to demonstrate that you're one of them or...

1:24:43 PA: You're worth that. You're valid. You're...

1:24:43 DR: Yeah, or whatever...

1:24:46 PA: You're to be taken serious and respected.

1:24:46 DR: Or they're gonna put you through some paces or ask each other questions and all that. And it really was just so not like that all the time. And once in one of the later conversations, I... There was this DVD. And I... It was a Robert Anton Wilson DVD and I was on it, a bunch of people were on it. And he had seen it. And then I was seeing him, I forgot where, probably at his house. And he's like... We're having some conversations about something and he's like, "Doug, I saw that DVD." And he's like, "You really don't understand what my work is about at all, do you?" And... But not in a way that, "Oh, I gotta know," like he's gotta correct the record, but he... Because you can't ever understand what someone else's work is really, really, really...

1:25:42 PA: Well, especially Robert Anton Wilson's.

1:25:44 DR: Yeah.

1:25:45 PA: Because it is so... It does have that element of mystery that's woven throughout everything in terms of...

1:25:51 DR: It's wink, wink, wink.

1:25:52 PA: Oh, it is. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

1:25:55 DR: And I was kinda saying... In the end, that his work is saying, "Believe nothing, believe everything." And he's saying no, that it's actually that there is something particular that he believes.

1:26:14 PA: And what was it?

1:26:15 DR: I don't know.

[chuckle]

1:26:19 DR: But what I got from it was when he says, "Keep the lasagna flying," it's sort like, "Walk around as if it's all true." 'Cause it may be. What's true, what... Who knows? But he would say that he's more involved almost in an amazing Randy way of turning over every stone and trying to figure out is this real or is this not? Are there people on Sirius signaling us through something or not? Or what are the... I kinda, on some level, threw up my hands to know, are there pyramids by aliens or not? I don't know, maybe. And it doesn't... On a certain level, it doesn't matter. What's the difference between an ancient and an alien? To me they're equivalent. They're as different from me is...

1:27:24 PA: That's so fascinating that you got to spend time with people like that.

1:27:28 DR: Yeah, it's the one good thing to being older.

1:27:30 PA: You know what I mean?

1:27:31 DR: Yeah.

1:27:32 PA: And...