Episode 5

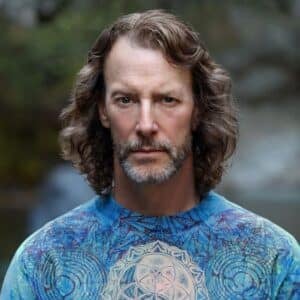

Gay Dillingham

On this episode of The Third Wave Podcast, we speak to Gay Dillingham: filmmaker, environmentalist and producer. Gay has just released a film 20 years in the making, “Dying to Know”, a documentary about the relationship between two of the most influential people in the history of modern psychedelics, Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert (or Ram Dass). The film brings us to face with the taboo of death and how the psychedelic experience can help our society come to terms with mortality. Here, Gay discusses the making of the film, along with her own encounters with death and tragedy, and how psychedelics could begin to change the way we view mortality.

Podcast Highlights

Gay begins by explaining that “Dying to Know” is a human story, about two men who were instrumental in bringing psychedelics to the forefront of modern society, and about the taboos that are hardest for us to talk about. Gay believes that through Timothy Leary and Ram Dass, we can approach death in a fresh and unique way, as a psychological transformation rather than an end of consciousness. And of course, psychedelics could be the tool to help us understand this concept.

Gay tells us that part of the reason for her getting involved in this film was her own personal history with tragedy. When she was 17, her 20-year-old brother was killed in a car accident; he had been the center of her world, and his death brought her to her knees. Gay says as a result of losing her brother, she had to grow up very quickly. She found that in death there is trauma, but also rebirth. This meant that she naturally became interested in the teachings of Leary and Dass, who espoused the thought of psychological rebirth.

However, Gay did not immediately fall in love with Leary or Dass. Her first encounter with Timothy Leary was during his lecture tours in the 80s – but she only saw the showman, not the person. When Leary announced to the media that he was dying in 1995, Gay and several other filmmakers decided to attempt to get Leary and Dass together to discuss their lives on film. Even though Gay was the youngest there, she was chosen to direct the film. She was familiar with personal tragedy, and had also read extensively around the pair, especially Leary’s book The Psychedelic Experience, based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Gay interviewed the two men in her living room in 1995, and taking from their example, decided to leave the setting open, allowing them to discuss their relationship organically. Gay gradually came to know the men as their human selves, rather than the caricatures painted of them in the media. The experience was very uplifting, says Gay, and it was clear how special their relationship was. It had genuinely affected a whole generation.

As the years passed following the interview, and Timothy Leary himself passed away in 1996, Gay felt increasingly guilty for not finishing the film. After seeking advice from Ram Dass, she didn’t give up on the project. Her experience of being fired from her job in environmental regulation in New Mexico (for being a ‘known environmentalist’, according to her new boss) prompted her to think about the cycle of life and death, and why modern humans struggle to address these big questions. She finished the film in 2014, and believes that it would have been very different if it had been finished ten or fifteen years earlier.

Gay points out that the important point of the film, the whole reason for its being, is to ask the questions about death that we are all afraid to ask. It doesn’t try to tell people what to believe, but tries to present a dialogue between two men who have a lot of experience. Leary and Dass even have different opinions on the matter anyway – and are often presented as two opposing views, one more scientific and one more spiritual. Gay says that for her, it reflects what’s going on in her own head; a conflict between science and mystery.

Psychedelics play an important role in being able to discuss mortality. The recent evidence from various studies, showing that psilocybin can help us accept death, demonstrates how psychedelics could help us face our fears. Gay states that it’s this ability of psychedelics to release the control of fear that led to their criminalisation in the 70s. Leary’s ideas were too radical, too anti-establishment, that he ended up being the first casualty of the drugs war.

Our discussion with Gay turns, inexorably, towards Trump. In an excellent essay by Charles Eisenstein, author of Sacred Economics, he discusses the things in life we are too afraid to confront or even acknowledge exist. Gay agrees and adds that, now our fears and shadows are more in the open, we have a chance to confront them more directly and break through towards liberation. And we now have the tools to help us face our fears better than ever before.

Gay talks to us about the impact her film has had with viewers from all demographics; even people who had not heard of Timothy Leary or Ram Dass, or had never taken psychedelics, were saying that the film meant a lot to them. Gay hopes that the film will start a dialogue about drugs and their role in helping us accept mortality. She mentions the rise of shamanism in modern society, and the successes of psychedelic churches such as the UDV and Santo Daime.

If you want to contribute to the growing discussion around psychedelics, you can sign up for a film screening of Dying to Know in your city. Screenings of the film are followed by discussions with various experts to help expand the dialogue around drugs and spirituality. As Gay says, film is the modern campfire, and we need screenings to focus our discussions.

You can also donate to the IndieGoGo campaign to receive a stream of the film, as well as additional perks.

Show Links

- Dying to Know – Movie Website

- Dying to Know IndieGoGo – donate for access to a stream of the film and other perks

- Apply to have a screening of Dying to Know in your city

- Follow updates on the current screenings of Dying to Know

- Biography of Timothy Leary

- Leary’s book The Psychedelic Experience, based around the Tibetan Book of the Dead

- Biography of Ram Dass

- Biography of Jack Kevorkian

- New York Times article about recent psilocybin studies investigating end-of-life anxiety

- Slightly older Johns Hopkins study investigating psilocybin and end-of-life anxiety

- Carl Jung and his concept of individuation – addressing the shadows in our lives

- Charles Eisenstein (author of Sacred Economics) discusses what Trump’s victory means for the future of our society

- Joseph Campbell’s interviews on The Power of Myth

- Ayahuasca church UDV

- Ayahuasca church Santo Daime

Podcast Transcript

00:29 Paul Austin: Hey listeners and welcome back to the The Third Wave Podcast. We have another excellent guest for you today. Her name is Gay Dillingham, and she is the director, producer, and filmmaker of the documentary Dying to Know, which is a historic film that covers 80 years of footage, and freshly addresses some of our most pressing contemporary taboos of death and drugs with consciousness and love. And so, today we're gonna dig into this film and hear Gay's story about why she made this film. We're going to talk about death and the concept of death and the role that psychedelics play in helping us to contemplate the edge that we all will end up one day going to. So, Gay, thank you so much for joining us.

01:16 Gay Dillingham: Thank you for having me.

01:18 PA: It's great to have you here. Yeah, we spoke in late November, I believe, for the first time. You, me, and Zack had discussed a few things about this documentary. And at that point you had shared the film with me and I went and I watched it, and I was really blown away by the subject material and how meaningful and how much emotion it really drew out of me. So, I just wanted to really thank you, first of all, for putting this film together and producing this and creating this.

01:52 GD: Thank you for being here now and really taking this story in. And I'm gonna tell the full title of the film, because it's, Dying to Know: Ram Dass & Timothy Leary. It's a portrait of a relationship. It's a beautiful human scale story that addresses these deep taboos and things in our human landscape that are not so easy to tackle or touch or talk about, but we're all wanting to, we're all dying to, if you know what I mean. And I find that through these guys, they are able to approach freshly death and rebirth as a psychological transformation, and also drugs as a possible vehicle. Drugs, but I say in fact medicine, psychedelics, as a tool for practicing that psychological death and rebirth. And these two guys had a real role to play in bringing these medicines to the west. So that's where this film was birthed, in 1995, at least for me. And yeah, it's been a nice, long journey and one that's been... Kept feeding me, so I kept [chuckle] working on it, and it's now been out theatrically. And so, we'll talk more about that as we go. How's that?

03:01 PA: Yeah, yeah, and so what... 20 years. That's a considerable amount of time. Can you tell us a little bit about preceding that, what really... Why this film? Why this relationship? Why this subject? And how has that really developed over the last 20 years as you've put this film together?

03:20 GD: Good. Thank you. Good question. Well, in some ways I've been answering that question now for 20 years or more. And let's see, I think the topics were really seminal or personal to me. When I was 17, I lost a brother, who was 20, in a car accident, who I just adored. He was the center of my world. So it kind of brought me to my knees and broke me open, helped me start growing up a little sooner than I would have otherwise, I think, growing deeper, perhaps. And I saw death as both a tragedy, but as a doorway, and I also saw how upside down our culture had become in the process, which everyone's gonna do. It's a natural cycle, death and rebirth. So, I started becoming fascinated with that, not only death of the body but death of... Psychological death and rebirth. And these two men had such fresh approaches, because they were the psychologists in the early '60s at Harvard who started experimenting with Psilocybin with graduate students and felt that they had found the elixir as psychologists, and then as beyond psychology. And in many ways, it's kinda what broke open the 60s from the 50s, the more [chuckle] somewhat repressed 50s. And I felt that their story, their relationship for me reflected that breaking open, that time when our society kinda went from being a square to a circle, or however you wanna metaphorically look at it.

04:50 GD: And I got to meet... I'm just gonna tell you a little bit of the genesis of it. I'd seen Timothy once in the '80s when he was doing his college circuit, promoting LSD. That time was Leary Software Design. He was a big pioneer in the cyber world as well. But in college, I was in college at the time, I thought it was interesting, but I didn't really see Tim the man, I saw the showman, the ego. And I wasn't all that impressed. Before that, I was 14 years old and I was listening to my brother getting in trouble for driving two hours into the city to see Timothy after he'd gotten out of prison, 'cause he was giving a talk in Oklahoma City. And I thought, "That's the first time I ever heard his name." And I thought, "I wonder why Matt was so... Risked this." Not that my parents were real disciplinarians, but... So, later on, it sort of evolved, and by the time... And like I said, first time I saw Tim, didn't really open my world that much. But to spend 20 years on a project, clearly, I became really deeply interested and curious. And as Tim was dying, it was 1995, he'd just announced in the media he was dying, and I was having dinner with a few other friends in the film business, they were all three older than I was, and they were real baby boomers, I was on the edge of that, and born in '65.

06:19 GD: We said, "This is a historical moment. Tim Leary is dying. What could we do? It would be interesting." And Andrew Ungerleider at the time came up with this idea to bring Ram Dass down from the Bay Area, 'cause he knew enough about their relationship, which I didn't at the time. And somehow we decided I would direct it. And that was a critical decision, because I was the one that was the younger and came in with somewhat beginner's mind, even though I was deeply affected by this time and generation. In many ways came through the death door because I had a brother that had died. I had also used this medicine at that time to heal myself as I was trying to grieve. And read The Tibetan Book of the Dead at the time as well as The Psychedelic Experience, which was Leary and Richard Alpert and Ralph Metzner's book, based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. It was called The Psychedelic Experience. So, they had identified psychedelics as a way to pre-experiencing these bardos that we go through from life to death, both the body, but the psychological bardos as well. So, we called Ram Dass, we called Timothy, we sent him a certificate from Jack Kevorkian who was the... [chuckle]

07:32 PA: He was the doctor from Michigan, I believe. Wasn't he?

07:35 GD: Yeah he was the death doctor.

07:36 PA: That assisted suicide. Yeah, yeah.

07:38 GD: Right, right. So, we gave him the certificate to Jack Kevorkian, which he thought was really funny, so he got... [chuckle] So he said, "Sure, come on over," and brought Ram Dass down. Later on, we realized, many, many, many years later that Andrew Ungerleider and he are cousins, Richard Alpert. So, in the end I ended up making a big family movie here, but very intimate and yet very universal in some ways. So, that first conversation that we put together, which was in Tim's living room, between Tim and Ram Dass, was really just a conversation between old friends. And I had given Ram Dass questions that I wanted him to cover and it was... But my goal, actually, as a director at that time was taking the lead from them with their real understanding and promotion of set and setting. The set I wanted to create was just comfortable, not controlling. We literally set them up, put the cameras up, and then tried to disappear, so that they could just have their moment. And I think that worked very well. On the other hand, the first time I went into the editing suite, it was like, "Oh my God, what have I done? It's just like anarchy. There's so much interruption or a cough." But in the end, there was a beautiful beautiful matrix. It just took a little while to find it.

08:56 GD: So, the portal of the film is the relationship. And I keep using the yin yang as a symbol because in many ways... In some ways, they are the symbol of the mind, the archetype of the mind speaking and conversing with the archetype of the heart. And as Ram Dass said to me not too many years ago when I used that metaphor, he said, "Oh, well, the mind." But Tim had such a big heart as well, 'cause we were using Tim as the archetype of the mind and Ram Dass and Richard as the archetype of the heart. So, he reminded me that Tim had a big heart. As he did, because seeing him on his death bed was beautiful. He was vulnerable, he was intelligent, humorous. So, I felt like for the first time I really got to see the man Timothy Leary, not just the showman.

09:40 GD: And then, Ram Dass, of course, is not just the heart. He had a very strong intellect. And once he had his stroke in 1997, had a 10% chance of survival, he really stepped into... Well, he always had been, but a real kind of spiritual teacher for a generation. But now he's also reaching into a whole new generation. He's a cyber speaker and he, like I said, 10% chance of survival, and he's been in a wheelchair now 20 years. The average that somebody's in a wheelchair before they die is five or six years. So, he's beaten all odds and he's just this incredible human being that has... Just in the time I've known him, since '95, I guess, we watched an incredible evolution of his soul and spirit. And he has practiced unconditional love, I think, so long in his life that he's living in that state pretty consistently, even though he's in pain and has all the other mortal bodily realities and things. He's a real model for all of us.

10:41 PA: I think one thing that struck me and probably struck our listeners as well is, I'd like to hear just more about the experience of being with Ram Dass and Timothy Leary that first time for you. These are two of... Especially now, in what we're seeing in this re-emergence of psychedelics and really coming into mainstream culture as more and more research comes out, as we hear more and more business leaders and thought leaders, specifically from Silicon Valley, advocating or talking about psychedelics, at least. I think we owe a huge debt or a huge amount of gratitude to what both Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert did in the 1960s. And so, what was that experience like being in the presence of those two luminaries in many ways?

11:31 GD: Well, I'm glad you cued it up like that because for a long time, not everybody saw it that way. Quite frankly, let me just say that I started this project without any agenda. I was not out to glorify or demonize either one of these men. I was fascinated by them because all I had inherited from my media culture was caricatures of these two men. And who I really got to know and meet and evolve with, were these really beautiful men, these human... And so, what attracted me was the human story. And for many, many... I saw he'd go to a lot of these conferences... Well, I used... I did. And scientific conferences on psychedelics. And for a long time, Timothy Leary, it was almost like the blanket statement at the beginning of any lecture by a scientist said, "If it wasn't for Timothy Leary having ruined it for all of us, the research would not have gotten shut down for 35 years." So, I thought, "Well that's interesting. How could one person really have done... " [laughter]

12:37 GD: It was the scapegoat model. And I really started feeling how dangerous that was. And Tim played a certain role for sure. He really felt he'd found the elixir and wanted to be the cheerleader of these substances. And yes, he was naïve, what was gonna happen, the kind of backlash. And he did early on fluctuate between these two poles, which was, for the sake of explanation, Aldous Huxley was more on the side of, "This is for the shaman class, the intellectuals, the artists, it's not for everyone." And then, the Allen Ginsberg side of the equation was to democratize it, "Put it on the streets, it's for everybody." And I know Tim went back and forth with those two points of view, and ultimately, it was out and it was going to be out and you couldn't keep this genie in the box, the bottle, anymore. And in many ways because it was so out, and even the government alone estimates 28 million people in our country have done psychedelics, which is a huge number really, if you think about a generation. And it means that there is that consciousness now out there.

13:42 GD: And that's, I think, why this research has been funded privately at John Hopkins University, at NYU and UCLA, for a while at UNM in New Mexico here. And the research, beautiful, long feature that came out in the New York Times December 1st, with the NYU studies using Psilocybin for end-of-life anxiety as well as alcohol addiction, and they've had incredible success with these two studies, longitudinal studies. And those scientists have seen the film. They actually came out with me in New York when we played there and are really supportive and really appreciate seeing the history and so forth. And the kind of conversations we're trying to have in the post-screening conversations around our modern campfire here is, how to continue with this medicine in a world that has signed up for a lot of pharmaceutical solutions, and yet we're really having a crisis of the spirit, and these medicines speak pretty profoundly to that if used well and thoughtfully. So, I'm encouraged and I'm really seeing our conversations deepen, and that's how I'm trying to use this particular story in this particular film.

15:00 GD: And we do have an Indiegogo campaign going right now just to fund that part of the community engagement that also enables me to give a stream of the film, tax deductible right now. Eventually, we're gonna let it be out digitally everywhere, but it is not yet, 'cause I really wanted to encourage and... Well, what's the word? Yeah, kind of force people into the theatrical experience, so that, in a world where we're so distracted by everything, whether it's on your computer your phone, whatever, at your home, it's hard to watch a movie and stay present, really engage a story. But in the theater, you turn your fun off, you're present with other people, you're being here now and you're absorbing in a way that you don't get to otherwise. So, we've had some incredible experiences. We've been in 80 different cities around the country, and then, most of those having these beautiful post-screening conversations. And through our website you can go sign up with your city to do a screening as well through Gathr the "Theatrical On Demand" model.

16:01 PA: And we'll definitely provide all those details as well in the show notes. So, if any of the listeners are listening through iTunes for example, if they go to our website they'll be able to find all those links, including the Indiegogo campaign. And we've even had discussions, a couple of discussions at the end of November, just in terms of as well engaging psychedelic societies. And there are more and more of these psychedelic societies that are popping up all over the States and getting people together that way and doing screenings. So, if anyone is listening to this who is part of a psychedelic society or who runs a psychedelic society, from my personal perspective, this is an excellent film to base a dialogue off of about death and about our elders in the psychedelic world, and what they've meant, what they continue to mean to us as we do push towards this new frontier of, hopefully, eventual psychedelic legalization. So yeah, thank you, thank you for sharing that. And with what you just mentioned, you mentioned this concept of absorbing. And again, I wanna get back because I think I still would like to hear more about that story of, when you were with Timothy and Ram that first time, what was it like for you to absorb? What was it like for you to be in the presence of those two?

17:17 GD: Well, first of all, it was just a very uplifting, inspiring, fun... There was just so much laughter and meaning from deep to profound. They're just... Together they were so dynamic and they had so much love for each other. And as Tim said the end of the interview, "Thank you for bringing us together so we can make love in public."

[laughter]

17:40 GD: And they had this incredibly dynamic relationship, without it being romantic or physical. Ram Dass is gay and talks about that in the film, which he had not really publicly talked about before, and Tim is not, so this was not... But this was a love affair of the soul. And that relationship then affected a whole generation, and it's still kind of expanding from there. So, being around these two guys, it was interesting, first of all having to wade through the caricatures that I'd been handed to me, to see the real men that were in front of me. And also, all the references they were making. Some of them at the time I didn't get or understand and later I had to go deep dig and research and, "What did they mean by that?" And then I'd go look in the archives. And so for me, that's why it became... This film made me as much as I made it. I then got to go find out. And the more I dug, the more interesting it got. And most things... Something holds your attention that long it should be fairly good.

18:46 GD: But there was definitely moments where I thought, "I'm just absolutely crazy. This story has already been told. Why am I so obsessed with this?" But in the end I think this was a different story the way I was trying to tell it. And being with them, I will say that... Tim died quickly. It was '95. He died May of '96. He was very generous to me. He would always invite me in. Was always... I don't know. He quickly trusted me. There was another documentary being done at the end of his life, which I won't even say what it was 'cause it didn't turn out so great and it was hard for him. But I also had some guilty feelings over the years up 'cause my life took over, I had a lot of other things I had to attend to besides film-making. And I started feeling bad I wasn't finishing the film. And at the end of the day I'd come back to Ram Dass throughout the years, and he was incredibly... To watch his growth and changes. We almost lost him so that was scary, back in 97. But one time I said, "I really have to hand this to someone else to finish because I just can't get it finished. I just don't have the bandwidth." Cause when you do something like you do have to disappear into it. You cannot be doing other things really.

20:00 GD: And he went into his silent... Closed his eyes and went into the place where he really feels things out. And he opens his eyes and looks down at me from the wheelchair, he says, "You'll finish it one day." Because he knew more than I even that it was mine to finish. And so I really appreciated that trust and that confidence. And I think also because it took so long, it's a different film than it would have been if I would have finished it even 10 years ago or 15 years ago. And I had to grow up with the film too, and with these two, with them, and keep learning. So I don't recommend as a business model. [laughter]

20:36 PA: Taking 20 years to produce a film? No.

20:39 GD: But sometimes things have to marinate. They have their own time. It wasn't like I was working on it. Obviously, I wasn't. I set it down for a lot of years and I'd just come back to it. But why I came back to it, is I think what in the end for me is interesting. I did a lot in the environmental world. I was in charge of environmental regulation and consumer protection for the State of New Mexico for eight years, and managed some of the most comprehensive greenhouse gas regulations in the country, dealt with nuclear weapons issues, traveled to North Korea twice. And I get to ask each of these kind of interesting characters, luminaries, that question. So...

21:19 PA: Yeah it is a challenging question, and it's one that I deal with and it's one that I think every single human deals with. Then as we spoke about before, our culture and the culture that we live in, the society that we live in, hasn't really given us the appropriate tools obviously to deal with that question because we live in such a materialist reductionist world. We live in a world where the sense of mystery and the sense of awe, and the sense of not knowing is even a taboo in itself to some degree.

21:48 GD: The drugs is the other side of that equation, I.e. The medicine. And if these medicines can alleviate our fear, we're not controlled like...

22:00 PA: Right.

22:00 GD: And that's why this period, these drugs now, and then, were so threatening. And what Tim was really advocating, "Think for yourself. Question authority." This is when soldiers across the world in Vietnam were starting to say, "Hey this is my brother. I don't wanna kill him. I don't buy this anymore." And it really started unraveling our nation state paradigm of why we were even going to war. And Timothy was put in prison. He was probably the first casualty of this current drug war. And he testified to Congress in 1966, which is a really fascinating footage, which is also in the film. And you can see at that moment why the clash of culture in this 50s culture absolutely not understanding what he was trying to describe through a psychedelic session. And it's not the only way to get there. There's other ways to get there, meditation and just life, to get to that place where you actually know that we are all one. So if you die, where do you go? But that was a very pivot point in history and the drugs played a big part because for the first time there was a huge population, the boomers and they weren't being controlled and they were starting to think for themselves. And Timothy was a spokesperson and an authority as a professor in his 40s, that was needed to, as his son Zac Leary said, to be put in prison for your ideas. It's pretty. You gotta really...

23:40 PA: Have some powerful ideas, right? A bunch of ideas. Absolutely. And so what... As from your perspective, in both in doing this film and just from your work as like you said working with the environment for so long, what has changed in today's world to make some of these conversations happen that were so clamped down on in the late '60s and early 70s? Why do you think we're seeing this re-emergence now of psychedelics?

24:11 GD: Yeah it seems to me, and I'm trying to figure this out. I think we're all shocked by this current regime change and where we've had with our politics in this country. And yet it's also not surprising. I grew up in Oklahoma and not a single county went to Obama during those elections. So I go back and forth. So I have somewhat of a real love and sympathy and understanding of mid-America and it's scared. We're changing fast. We're saying climate change. We've gotta get out of fossil fuels. We've gotta move forward and we're changing people's lifestyles. And the fear factor, I think, was bigger than the rest of us understood. And I also do a lot of dream work and I think the shadow has been here, and this might be our opportunity to integrate the shadow 'cause you can't integrate until it becomes revealed and you can see it. So I'm hopeful in that way. I'm also pretty terrified at how much damage we can do fairly quickly. So I understand why the voters rebelled between both the Democrats and the Republicans in this election. The people we have got to get involved. We've gotta jump in. We've gotta participate. And it really this is not dress rehearsal.

25:34 PA: When we had our call and when I talked to you in late November, you had mentioned the shadow side, and I've read a little bit of Carl Jung, and he talks about this concept of individuation, which is integrating that. But can you just explain a little bit more about the shadow side? What is the shadow side, and what does that mean to integrate the shadow side?

25:53 GD: Well, I think... I'm no expert, but the way I understand it, it comes in our dreams. It's that character that may be chasing you that you don't turn around to look at, it's just something that's chasing you. It's the unknown; it's the thing that is under, in your subconscious that is driving you, but you don't know what it is. That's personal, but we have collective shadow too, and have societal shadow. And I think that, partly because we haven't been listening to each other, or truly listening to each other, is why this particular election surprised many people, and I think an obvious, kind of, the shadow reared its ugly head, too, in the Hitler-Nazi period. And when you start demonizing the other and scapegoating the other, which is what we're doing now [chuckle], that's when we start down a path of real danger, and our children are even mimicking what they're hearing now on the TV and speaking out against their classmates, whether they're Hispanic or Black or White, or... So we are definitely in some dangerous territory, and because we're voicing it and it's out there, it gives us the opportunity to address it, and it's gonna have to be at all levels of society and all levels of family, and in our own psyche as well as our politics.

27:27 PA: Absolutely, and I think when you're talking about this -this side of the shadow side, the side of now the necessity to engage the side of now that we are actually looking at what's been haunting us, that we now have to face it, that we now have to get together, reminds me of an essay that I read by Charles Eisenstein, who is the author of a book called Sacred Economics, and I'll just read the first few paragraphs here. I don't want to read the entire thing, but talking about this really reminded me of that. I'll link to the full essay in the comments as well, but just, I'm gonna read the first three paragraphs, and it's basically... And what he says is normal is coming unhinged. And this is of course in reference to the... This was on November 10, 2016. So normal is coming unhinged. "For the last eight years it has been possible for most people, at least in the relatively privileged classes, to believe that society is sound; that the system, though creaky, basically works; and that the progressive deterioration of everything from ecology to economy is a temporary deviation from the evolutionary imperative of progress. A Clinton presidency would have offered four more years of that pretense. A woman president following a black president would have meant to many that things are getting better.

28:40 PA: It would have obscured the reality of continued neo-liberal economics, imperial wars, and resource extraction behind a veil of faux progressive feminism. Now that we have, in the words of my friend Kelly Brogan, rejected a wolf in sheep's clothing in favor of a wolf in wolf's clothing, that illusion will be impossible to maintain. The wolf Donald Trump, will not provide the usual sugar coating on the poison pills the policy elites have foisted on us for the last 40 years, the prison industrial complex; the endless wars; the surveillance state; the pipelines; the nuclear weapons expansion, were easier for liberals to swallow when they came with a dose, albeit grudging, of LGBTQ rights under an African-American President." And he goes on then to talk about continuing this. So... When you... And I'm gonna link to the full essay 'cause I would highly recommend everyone...

29:30 GD: Oh my God, brilliant, brilliant.

29:32 PA: Because it is a really good essay, and Charles Eisenstein in general is one of my favorite writers. But talking about that shadow side, the necessity to face it and the necessity to come to terms with it, of course then also it comes right back to the conversation that we've been having before as well, of what this film is about, and in some ways it's about having to come to terms with death; it's having to face death.

29:55 GD: So let me just add something right there, because I'm so glad you read that; that was brilliant. And I did a terrible job earlier of trying to say what is the shadow and what do I mean. It's actually pretty practical; whether you're in a psychedelic state and you come up to that, 'cause some people say "Oh, a bad trip." Well most trips have a period where you get squeezed and you're challenged and you have to break through, and if you break through you get to a beautiful liberation, or on the other side of it. And that happens in the dream state too; we have the set and setting and the action, and whatever the psyche is dealing with in that dream, and usually no matter how many vignettes or dreams you have in a night they're all the same kind of issue in your psyche. But there's always that place that you come up, not always, but often, when you come up to this place where you stop. There's fear, there's death, there's something that's blocking you, and most of us stop at that place, whether it's in a psychedelic session or in a dream.

30:53 GD: And if we could practice breaking through that; in the dream world it might be, "Oh, here's this animal", but it's okay. Let the animal eat you. Then you transform into something else and there's an answer in some other beauty on the other side of it, or you die; what you think is you die, but you actually then transform it into something else. So in the psychedelic session you're breaking through those places that are so fearful, and it's natural to be fearful. So that's why I guess I'm very hopeful, 'cause at the same time we feel like we're going backwards, we're actually... Have potentially more tools to help us.

31:29 PA: And that's an excellent way of putting it, by facing it, by accepting as it is instead of trying to run away from it we can, I think, come to grips with what we're actually dealing with, both if we're talking about dream work in the shadow side, but also on a more concrete, realistic basis with the discussion about the political climate at the moment, and do what's necessary, whatever is necessary to be able to, like you said, re-emerge and re-transform as anew, but a healthier, a more cohesive community of individuals and of people. Yeah, I think you've hit it right in the dot, absolutely. So, let's get... Roll back a little bit. I would like to hear a little bit more just about this documentary about... I would like to talk a little bit more about this concept of death and this concept of dying. And maybe if you could just tell us a little bit about the process of filming it. So, you obviously spoke about when you had Timothy and Ram Dass together about 20 years ago, in 1995, when you first shot that footage. Was that, then, the only live footage that you shot with them? Did you...

32:44 GD: No, yeah, pretty much everything since '95, was the footage I shot. '95 was the dialogue between the two of them. And then, I went back to Tim before he passed away in May and had the single interview with him. And then, he passed, did the funeral, and all, which was incredible. And then, we did... There was a narrow window, actually, after Tim had died, but before Ram Dass had a stroke. So, that single interview with Ram Dass in the film is in that window of time. That first footage was '95 and '96, then I set the film down for a long time. Ram Dass was recovering, I had more death in my family, all kinds of things, and then I came back to Ram Dass in about 2002-2003 and did some more footage. Again, 2009-'10. Well, I saw him in between them, but I wasn't shooting. And then, I didn't do all the ancillary interviews until 2011-'12. So, that's kind of the process of it. But I also wanted to ask you, if you don't mind, where did the film leave you? Where did it take you? What was your experience watching it?

33:55 GD: Yeah, that's a really good question. I think, for me, death has always been something that has really been on my mind since my first psychedelic experience when I was 19. And it's a concept that still comes up from time to time. Like you, I also was raised in a fairly conservative Christian home, attending church every Sunday like you. I lived in a very... From Grand Rapids, Michigan, which is a very conservative part of the United States. So, this concept of death was always... Saw with it from a Christian perspective, which was the sense of heaven and hell and a sense of sin, repentance, and whatnot. And so, with that first psychedelic experience that I had, it obviously shifted my thoughts on it dramatically, in terms of how I perceive death, in terms of how I perceive the process of dying, and as well as I began to read more and more about things like the mystical experience and reading books like The Tibetan Book of the Dead, it gave me different perspectives on it.

34:54 PA: And so, I think watching this film put me back into that transition in my life, put me back into that transition of going into some of my psychedelic experiences themselves and understanding what death meant to me and those... And then, seeing that play out between these characters, between Ram Dass and Timothy Leary, it brings up a lot of emotion and it brings up a lot of difficult questions, and it brings up a lot of engagement. And for me, it was just a really, really stunning, beautiful way to contemplate, again, have, like you mentioned, a time and a place where I was completely focused. And in this film, to really think about, I guess, from my perspective, what death means to me. And I think contemplating that and having space to contemplate that is one of the most powerful things that we can do as humans. And so I, think that was, for me, it brought me back to my first experiences, it brought me back... Of course, I've read extensively about Timothy Leary and Ram Dass, and so, to see these characters in that light, in a very vulnerable light, I thought was powerful. Yeah, I just thought it was a beautiful moving piece and I think that's probably the best way for me to describe what it did for me.

36:10 GD: Good. I had this... It's interesting, 'cause some people say, "Oh... " The baby boomers are an obvious audience for this, but I have a lot of people, whether they're young people interested in psychedelics, but young people that have no clue who these guys are that have nothing to do with psychedelics. [chuckle] This young Spanish girl who was 18 years old, said to me after the film, she said, "This film makes me wanna live more and love more," and that really made me happy. [chuckle]

36:38 PA: Yeah, yeah, and I think that another really good way of putting it is, again, from my personal perspective, the psychedelic experience, it brings you into this process of rebirth and re-emergence and rejuvenation. And again, I think, for me it's specifically been because, as we talked about before, this concept of breaking through the fear of death, of breaking through to going into the mystery and the awe, and understanding what that means and coming out on the other side with this renewed sense of energy and rejuvenation for life. And so, I think that that's great. What else have people told you about it? I think that's another great thing that I'd like to know. What else have people told you about the film? How have people then moved by the story that you have told?

37:26 GD: The other piece that really means a lot to me is when we go in a city sometimes, I will see the same face come back, like, "Didn't you just see this last night?" [chuckle] So, I had people see it two, three and four times, without much time in between, so they keep coming back to watch it, which is a wonderful thing because they tell me that they get something different out of it every time they watch it. So, there's multiple layers to it, because it's a contemplative film. We have also opened film series, like the Meditative Life film series up in New York at the Film Center there and the Buddhist Film Festival in Amsterdam. And so, that's wonderful that it can be repetitive. I've had people say they really want to watch it when they're close to their own dying, or they wanna show it to someone that is either dying or tending to, helping someone they love to die, to help that midwifing through that rites of passage. So, in essence, a lot of what I care about and why I focused on these particular things in this film is because we don't do a good job in our culture of rites of passage. And by missing that, I think we have a somewhat perverted relationship to drugs, 'cause that's...

38:50 GD: Young people, that's a rights of passage, but if you don't do it consciously and well it's pushing the envelope, which is really what rights of passage is, and it's good to have guidance. And then the other more obvious rights of passage is the end of life passage, and we don't do that very well either. We're getting better at it, and we have more hospice available and a lot more soul-centered kind of options, but even...

39:17 PA: It's still lacking. There is... And I am glad that you even... We had kind of talked about, or touched on this earlier in the conversation, but this lack of ritual, this lack of initiation, that we have, this lack of acceptance, that we have in our culture. Joseph Campbell is... He has written extensively. He was the pre-eminent writer on Onthology, at least...

39:40 GD: Oh.

39:41 PA: From a Western perspective, and he did these interview series, The Power of Myth. Have you watched this with Bill Moyers? PBS?

39:47 GD: Yeah, I love him.

[chuckle]

39:49 PA: Okay, yeah, they're phenomenal. And Joseph Campbell mentions in these interviews how the reason we see so many ills in society today is because of this lack of ritual, and this lack of initiation, and this lack of creating spaces for people to come to terms with... In his specific case he was talking about being a man, going from that point of being a boy into being a man. And also talking about death as well, and how, like you mentioned, drugs, they tend to be this entranceway into the sense of ecstasy, and the sense of awe, and the sense of reverence that are... Like in a materialist, reductionist, a very scientific society has done away with, and... Yeah, so I think that it's...

40:34 GD: Yeah. Yeah, I know it's interesting. We've gotten so literal that we've lost the magic which means we've lost some of our human dimension, and it's interesting we're trying to find our way back to that integrational. And it's the poetry of life, it's the things that are being said. [chuckle] And it's incredible that we do have these medicines, and in large part we're also in the process of regrowing what would be our shaman or our healer or our seers and pathfinders in our society, in the movement with Ayahuasca, and the UDV Church having won, and the Santo Daime having won the Supreme Court... All the way to the Supreme Court unanimous decision to be able to drink the Ayahuasca tea. There's a nice Nucleo church here in Santa Fe, and it's a pretty beautiful community. So we are growing it. It's new, but it's happening.

41:33 PA: Absolutely, it is happening. I just have one more question for you, and feel free to answer this in any way you like, how did your personal experiences with these medicines influence your decision to make this film? And maybe you... I can't remember if we specifically addressed this or not, but did you have any... You kinda had briefly touched on it when I was... When we were talking about your experience when you were younger, but is there any, really, experience, specific experience, that you can think of, or that you can... That you'd like to talk about that influenced your decision to make a film of this magnitude?

42:10 GD: Let's see. Good question. Well, I touched on this, I mentioned it earlier that when my brother died I really was, really brought to knees. I was in... Suicide was one of the things that really brought me back to life. And who knows what would've happened without that. A number of things happened also. So my relationship with the drug conversation is also influenced because my mother had been drinking very heavily after... At the end of my parents marriage, and so I witnessed a few years of some pretty severe alcoholism, and she quit drinking two weeks after my brother died. So at the same time, I watch her really resurrect. And I started going in, this is in the 80s in Boulder Colorado, going to Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, and really learning from incredibly beautiful people that... Sensitive and beautiful people, Vietnam Vets, and... So I realize now the older I get how fortunate I was to have some of these tragedies that then became silver-linings and openings, and I was fortunate enough to have two parents that really supported and loved me and gave me a lot of freedom to be me, and [chuckle] somehow trusted me.

43:31 GD: But, I never really treated this medicine as a recreational party thing. Even though it can be fun, it can be social, it was really self exploration, and maybe because I had such a seriousness happen kinda early in my life, but... And I do like to have fun and... Obviously, but I think relative to why I wanted to make this film with this particular content was because I realized that this idea of death, the other side of it is really love. And we really are all one. [chuckle] It's not just like an idea. So, feeling that and really practicing that with each other is so rewarding. And so wherever I have a chance to bring these conversations about, in many ways the conversation that started at dinner the night Tim announced he was dying in the media, then became a conversation between Tim and Ram Dass that we filmed, and so we're carrying that conversation as it... The filmmaking team were... We're carrying that conversation now out to others to say let's carry on the conversation. So, and I also just wanna give a big shout out to all the incredible people that made this film possible. Obviously it takes a village, executive producers that put money in, believed in this, my editor that worked with me, put up with me, David Leech.

44:54 GD: Town composer Steve Postell, brilliant composer, visual people, Dustin Lindblad, Colin Gill, who I'd always had that mandala in this particular interface in my mind but tried to do it and it felt too computerized and too synthetic, so Dustin, this beautiful illustrator drew all these mandalas out and then we started animating them. So that was fun. And gosh there are so many people to thank. I just... Oh and Robert Redford, bless his heart. To get his attention, the master storyteller, and I'd seen him... I'd worked with him before a little bit on the environmental front. And he narrated an earlier documentary I did on radioactive waste. But I saw him in his wife's opening and he was still in the rough cut stage with my voice as a narrator and still pretty rough. And I just said "Hey would you mind looking at my documentary?" like 1000 other people ask him. And he said yes 'cause he knew these two guys and they had actually impacted him. And Ram Dass really did help him out at one stage in his life.

46:00 GD: So first of all, he and Billy, his wife, watched the film and he calls me the next day and just kinda talked for 10 or 15 minutes and really understood the film and what I was trying to do. And I was just stunned 'cause I actually had not thought of asking him to narrate. I thought I needed a woman's voice to balance the male story. So I was complaining Susan Sarandon had not called back. But he said, "Yeah she's busy." So I said "How do you feel about?" Anyway, so he narrated the film, but more than narrating the film he sat with me in my little hot office one summer day with notes and the transcripts and really helped me with story structure and gave me his notes. And went into it a little skeptical, I'm embarrassed to say 'cause I wasn't sure if he understood what I was doing. I thought he might be more interested in the biographies than really the what I was trying to do which was a fresh look at death rebirth and all that other stuff. But he was so spot on. What a master. Oh my god. I agreed with 95% of what he said and I executed probably 90% of it. So to get, obviously, and it's not like... I looked at him at one point and I said "You are worth every penny." I just told him wasn't able to repay him for his brilliance. So just people that believed in it, that have lent their hearts and minds and money and everything. I just am eternally grateful. So thank you for letting me take a moment to say that.

47:26 PA: And thank you for paying tribute to them. I think saying those names out loud is important. When I was at the Horizons Conference in October and Bob Jesse who runs up the council Spiritual practices.

47:37 GD: Oh I've asked about him. I wanna meet him.

47:39 PA: Yeah, Bob, I haven't met him but just the talk he gave at Horizons was phenomenal. And before he started his talk he publicly acknowledged some of his mentors and leaders including Huston Smith, who we have spoken about earlier. This is back in October during the conference. And so I think providing that space to let people do that I think is very powerful and impactful. So thank you for acknowledging those people and thank you for mentioning them. And Gay thank you for your work and putting this film together. Just from my own personal perspective it was a really moving piece and you did a phenomenal job. So...

48:15 GD: That means a lot to me. Thank you very much. It put me together. Yeah.

48:22 PA: Good to hear. Good. Well so you guys are running an Indiegogo campaign at the moment.

48:27 GD: Yeah.

48:27 PA: So what's the URL in terms of just the...

48:30 GD: Why are we doing it? Yeah, well first of all our website you can get to the Indie from that as well. So dyingtoknowmovie.com is our website and then the Indiegogo campaign is up for about another maybe 28 days or something like that maybe a month. And the idea what we really want to do is keep the community engagement going, keep these pro screening conversations going. So I invite luminaries in from each community where we're showing it whether they intersect drug policy or end-of-life hospice various people from that community to come facilitate a post-screening conversation. And that's been working really well. It's really sweet. Some of my get to go to or one of the film... One of our team gets to, like Zac Leary. But a lot of times we just invite people in and they do it without us. And that's great.

49:21 GD: So this Indiegogo campaign also allows me to... And it's all charitable tax deductible which is cool. And I can give a stream of the film now before it's commercially available which I'm not sure exactly when that is gonna be. So if you go to or Indiegogo campaign for $25 you get the stream and thank yous. And then there's other wonderful perks including some signed stuff from Ram Dass and various... And you can also gift for... You can get a discount to gift five different streams to friends or whoever you'd like to give them to. And that is tax deductible which is nice. So yeah, I just back to this idea of the modern camp fire I think where we... This is where we tell our stories. Film is how we tell our stories. And it's nice to have focus time together and we wanna keep that going. So that's why we're doing the Indiegogo.

50:17 PA: Absolutely, absolutely. So dyingtoknowmovie.com. And I would highly recommend, yeah, everyone who is listening this to go and both support the Indiegogo campaign and watch this film as soon as possible because it will be a moving film for whoever watches it. So...

50:34 GD: Well, thank you Paul. This has been a real treat to just hang and chat with you.

50:39 PA: Yeah it's been great to chat with you as well. So thank you so much for taking your time with us and thank you so much for being on here. And it's been a real pleasure.

50:49 GD: Cool, well thanks to all your listeners and friends out there on your podcast. So stay in touch. Keep the faith.