Psychedelic research has given us so much. Thanks to the revival of psychedelic science, we’ve (re)discovered that psychedelic therapy can benefit sufferers of severely debilitating conditions where current treatments fail, such as depression or addiction. We’ve started to develop an understanding of what psychedelics do to the brain, and how psychedelics can have such transformative power…

But there’s still something missing.

The “physicalist” view of reality struggles to explain the phenomenological aspects of the psychedelic experience.

Why is the mystical or spiritual experience so valuable for healing? Why does our mindset matter so much in determining the effects of a psychedelic? Why, after all is known about the brain, can we still not explain the correlation between physical structures and subjective experience?

This last question is known as the “hard problem” in philosophy. Why do brain states, fully mappable in physical space, correlate so well with our subjective experiences of the world? What links the two together – and why does a complete physical understanding of the brain still fail to explain the place of conscious experience in a material universe?

In other words, why should a physical configuration of particles correlate with your experience of, say, the color red?

The current trajectory of psychedelic science means it will confront these difficult questions starkly in the coming years. As we inch closer to a full understanding of the physical brain states that psychedelics can induce, we have to consider what this understanding means for our experience of the world.

A recent heated exchange of ideas (and subsequent back-and-forth on social media) between leaders in physicalist psychedelic science and psychedelic philosophy has brought this conflict into view.

What is the source of this friction? And why does it matter?

Let’s summarize…

The Players

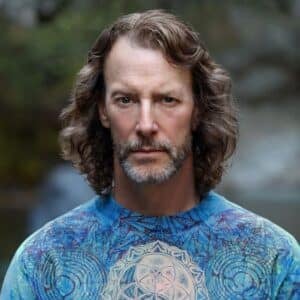

Bernardo Kastrup has been dubbed by some as a “psychedelic philosopher.”

Originally an expert in artificial intelligence, Kastrup now writes extensively about how psychedelics can point us towards a theory of mind that effectively accounts for the “hard problem” of consciousness – or at least, to a greater extent than the physicalist philosophy of the current scientific paradigm.

Alongside Kastrup is Professor Edward Kelly; a cognitive neuroscientist with an interest in challenging materialist dogma regarding the mind-brain connection. He joins as a concerned expert who is critical of the direction of psychedelic science.

On the other side, Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris is the head of psychedelic research at Imperial College London, and has been at the forefront of some of the most significant advances in recent psychedelic science.

Carhart-Harris is joined by Dr. Enzo Tagliazucchi, a physicist and an expert in neuroimaging techniques. Tagliazucchi has also been involved in some of the most influential psychedelic research of recent times, and could be considered an authority on the technicalities of modern brain imaging.

The Opening Argument

This debate began with a piece in Scientific American, written by Kastrup and Kelly, criticizing the leaders of the psychedelic science movement. It proposed that during recent media appearances by Carhart-Harris and others, the results of the scientific studies have been overstated and misrepresented, and that these scientists are committing confirmation bias (prioritising results that fit their prior framework of the world).

The typical “physicalist” model of the world expects that increases in activity of the neural correlates of consciousness would result in increases in the richness of consciousness. If there are more complex interactions taking place in areas brain associated with conscious experience, this should correlate with a more complex “feel” to consciousness; a more extensive and dense subjective experience (such as that associated with psychedelic experiences).

However, according to Kastrup, recent research consistently shows only decreases in brain activity during psychedelic states. If only decreases are observed, it seems unlikely that enough neural correlates are increasing to the required level for such rich experiences. Additionally, other consciousness-rich states like dreaming or near-death experiences have been found to correlate with low brain activity.

Kastrup states that scientists have communicated their research poorly, in a way that infers that brain activity is actually increasing during psychedelic states. According to Kastrup, findings that only show brain activity becoming more variable are being presented as evidence that brain activity is increasing during the psychedelic experience.

Overall, Kastrup argues that scientists are at best oversimplifying their research, and at worst purposefully miscommunicating their results in order to confirm the physicalist model.

Kastrup instead proposes that other metaphysical frameworks of reality, such as idealism, could explain these scientific findings without the need for misrepresentation. “Reducing valve” theories of consciousness, that consider consciousness a more fundamental aspect of reality rather than just an epiphenomenon born from a physical brain, could be the key to reconciling scientific findings with the “hard problem” of consciousness.

Kastrup ends by calling on the leading scientists of the psychedelic movement to consider alternative frameworks of consciousness, to avoid getting mired down in physicalist dogma that could hold us back from a true understanding of mind.

The Initial Response

Carhart-Harris, Tagliazucchi and other researchers responded to this article with their own editorial in Scientific American. They argue that Kastrup and Kelly have misunderstood the research, and are themselves twisting the facts.

The scientists argue that their findings showing the increase in signal “diversity” (a synonym here for “randomness”) during the psychedelic experience are significant, despite being small. They argue that they were never setting out to explain consciousness – but merely to find the physical correlates of mind-states.

They argue that the gap in understanding is the natural result of being at an early stage of psychedelic science, in part characterized by reliance on methods and technologies that are not fully sophisticated.

Additionally, the authors argue that most findings in fact do point towards increased brain activity during psychedelic experiences, and that Kastrup and Kelly have overlooked the subtleties of these studies. Unfortunately, the scientists do not give a detailed explanation of this: which is certainly required, since previous research from their own laboratories has repeatedly found (apparent) decreases in overall brain activity.

The scientists end by dismissing the philosophical aspect of this conversation. Confusingly, they state that the debate around the link between physical brain states and subjective experience is “entirely irrelevant” to their research.

The Fallout

For proponents of idealism and similar philosophical worldviews, this response from the researchers was exactly what they could have expected: scientists unwilling to address the philosophical issue at hand, or consider that their current framework of consciousness is inadequate.

For those in the physical materialism camp, they were being pulled into a very familiar argument: one with opponents who were not willing to accept the materialist scientific paradigm at face value.

The debate continued with three follow-up articles from Kastrup and Kelly, repeating the points that they feel have not been addressed by the researchers. A sharing of prior email conversations reveals that Tagliazucchi and Carhart-Harris seem to be contradicting themselves in some regards.

This prompted a tense exchange of words over Twitter. Kastrup argued that the scientists have simply not addressed his criticisms, and are repeatedly skirting the issue. Very quickly, the Twitter conversation turned sour: Tagliazucchi criticized Kastrup’s lack of scientific knowledge (despite having Kelly’s expertise on his side), while Kastrup accused Carhart-Harris of blind dogma and a refusal to engage in discussion.

Although Carhart-Harris appears to have rejected a consideration of philosophical alternatives, Tagliazucchi continues to engage, and the conversation between him and Kastrup has been stimulating.

Why Does This Conversation Matter?

The take-home message is that psychedelic science has taught us a lot about the brain, and how we can treat mental health conditions more effectively – but there may be severe limitations in what a science based in a physicalist framework can tell us about conscious experience.

The ability for us to discuss these metaphysical issues is vital to the survival of the psychedelic movement. It is especially crucial for the scientists at the forefront of the community to be able to field criticism with humility and consideration. Otherwise we risk the psychedelic renaissance turning into something of a psychedelic regime.

One thing the psychedelic experience can do for us (and thankfully, this has been scientifically proven) is open our minds. Make us more receptive to new ideas and concepts. Break us free of dogma.

Perhaps all of those involved in this discussion would benefit from practicing what they preach. An open mind is not only a part of being a compassionate human – but also a requirement for good science.

It’s understandable why the scientists involved in this discussion may not feel the need to engage fully with Kastrup and Kelly’s points. Their current physicalist framework of the world is working – they have seen success and popularity, and are effectively contributing to the growth of neuroscience.

But they must realize that the psychedelic community is based on more than just physicalist science. Even if Kastrup and Kelly’s ideas are false, and if physical materialism holds the key to our understanding of existence – their criticisms must be met, and met with an open mind.

Otherwise, we risk falling into a realm of dogma and lack of self-awareness that is, let’s be honest: very un-psychedelic.

The author can be reached on Twitter @rjpatricksmith

What the physicalists overlook is that the entirety of their view exists, in and because of, consciousness.

All that is known, is known in consciousness – full stop.

How can the physicalists be sure of their knowledge of anything without understanding, and taking account of the field in which such “knowledge” resides and derives it’s existence?

Physicalists are off chasing the notion of consciousness being a unique and separate instance for each individual generated by the individual brain. They are going to be chasing this without result, as it is not correct, rather, the fact of being is that consciousness is a fundamental of existence, and is unitary, there are not multiple instances but, just one consciousness despite the common experience of “knowing” only the contents of one’s own mind.

In the fact that sensory experience is not a direct perception of what is real, but rather a species-specific representation of reality trimmed and tuned to benefit survival and selection, we have reason to seriously question the “self-evident” pronouncements of the physicalists and naive realists.

We don’t see “the Stop sign” we perceive a representation of “a Stop sign” in experience.

Great article on the current conversation!

Look people.

I would just like to be able to get on with having a psylocibin experience however I don’t know where or how to obtain the shrooms for the task I draw a blank everywhere.

I live in Queensland Australia and it’s illegal to pick or grow shrooms just like most places.

Any advice anyone?

Hello, due to legal restrictions we cannot share or allow for the sharing of any information that pertains to sourcing illicit substances. We hope that the legal status of psychedelics will change in the near future to allow people to legally and safely access psychedelics.

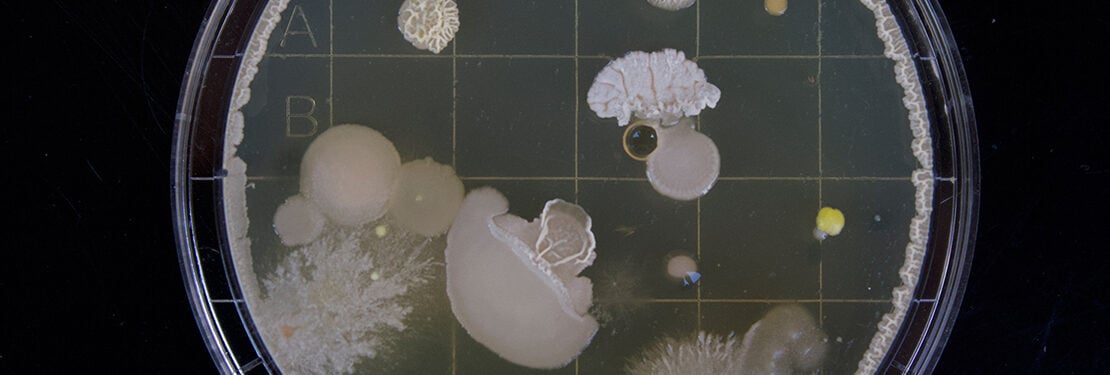

Purchasing spores for microscopy purposes is perfectly legal in Australia. However cultivating those spores into fungus is illegal. Its unfortunate some countries are so shortsighted to not allow this.

A great and timely article, and one that I hope highlights the issues around research into entheogens.

Drawing attention to confirmation bias is IMHO a first step in challenging the “big pharma” drive to weevil into position with government. By that I mean continuing the same narrative (read mantra): that psychological problems are founded on brain chemistry.

The drawing back from conversations on the philosophical implications of psychedelic experiences raises the questio of “who funds the research”, which leads to “who decides how this research benefits society”?

I think the avoidance of broader (and much needed) philosophical debate comes down to funding. If the institutes involved peddle the same materialist worldview, they improve the likelihood of receiving funding.

To change “entirely irrelevant” to “entirely relevant” invites a crack in the vessel of our global civilization’s paradigm: that there is more to our embodied selves than mere matter, that individual and collective consciousness (which includes all life) may be more than an epiphenomon of complexity in 4 dimensions (as Jung tentatively suggested).