Psychedelics have held a contested place in the collective cultural imagination for most of contemporary history. As a catalyst for the counterculture movements of the 1960s and subsequent culture wars that led to their outlaw, the perception of hallucinogenic drugs such as psilocybin, LSD, and peyote (to name a few) have fallen into two distinct camps: revered and reviled. For some, psychedelics have always been (and continue to be) dangerous substances that cause permanent damage to the brain. For others, they hold the potential to actually heal the mind, and treat some of the most prevalent mental and behavioral disorders.

Over the past few years, we’ve been lucky enough to see this stalemate shifting, thanks to the rise of the psychedelic renaissance—the resurgence of research into the healing potential of psychedelics. But even with a growing body of research, for many, the idea of widespread and unfettered access to these mind-expanding medications is a hard pill to swallow. Despite growing scientific support, the propaganda that cast psychedelics as dangerous left their mark. On top of that, many enthusiasts fear that one slip-up (a high-profile death or injury, perhaps) could effectively put the lid back on this burgeoning movement, leaving many to ask: At this crucial moment, what is the path to widespread societal acceptance of psychedelic use?

The answer may just lie with microdosing. Defined as the act of consistently taking sub-perceptual doses of (almost) any psychedelic, microdosing has been touted as a way to help treat the symptoms of depression, addiction, and anxiety, as well as boost creativity, productivity, spiritual connection, and overall wellbeing. And, perhaps even more than psychedelics in general, the practice of microdosing is steadily making its way into the mainstream.

From underground to above board

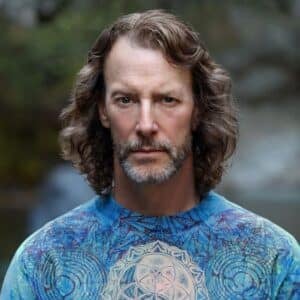

For years, microdosing was practiced quietly by a select group of self-experimenters in the underground psychedelic community. But after psychologist and psychedelic advocate Dr. James Fadiman published his 2011 book, The Psychedelic Explorer’s Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred Journeys, microdosing saw a major revitalization. This signal was boosted further when Fadiman appeared on investor and author Tim Ferriss’s podcast in March 2015, which prompted his large audience of self-experimenters to try it for themselves—and effectively set microdosing on the path to becoming a normalized, mainstream practice. Dozens of high-profile publications have since published exposés on the topic, and Silicon Valley self-optimizers have normalized its use in the workplace—and beyond. Consider, for instance, the GQ headline, “Micro-dosing: The Drug Habit Your Boss Is Gonna Love,” and The Guardian’s “‘It makes me enjoy playing with the kids’: is microdosing mushrooms going mainstream?”

With mothers and CEOs alike openly microdosing, this steady progression into the mainstream shows why microdosing could be paramount to the future of psychedelics: it can lower the barrier to entry. While it’s reasonable to assume there’s long been an overlap in the Venn diagram of tech workers and the psychedelic underground (after all, it’s well-known that Steve Jobs used psychedelics, and some have even credited the substances with the invention of the internet), it’s also possible that if Fadiman had recommended that Ferriss’s followers go out and take an ego-dissolving dose of psychedelics, many likely would have passed. By taking a sub-perceptual dose, however, people curious—and perhaps hesitant—about the benefits of psychedelics can find a gentle entry point into the larger world of their use.

A new standard of care

Getting the vast majority of people comfortable with taking large doses of psychedelics isn’t the point, of course; not everyone needs that. But getting people comfortable with the idea of psychedelic use is key to their widespread dissemination to those who do need it—psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy could become legal if popular opinion can override governmental trepidation. And getting psychedelics legalized could be vital in face of the world’s growing mental health crisis.

“It would be much safer if it was legal, so you could openly seek expert advice,” a mother named Rosie, who struggled with her mental health and a drinking problem until she discovered microdosing, told The Guardian. “I’ve taken antidepressants with lists of side-effects as long as my arm. Now I’m taking something with no known side-effects and it’s working… And I’m significantly happier as a consequence.”

Like Rosie, some 13% of the global population (or nearly 971 million people) suffers some kind of mental illness, according to the Institute for Health Metrics Evaluation. In the U.S. alone, antidepressant use has gone up 60% since 2010, with 25 million adults now on antidepressants for more than two years. Suicide rates are rising, loneliness has become an epidemic, and feelings of meaninglessness are pervasive, suggesting that humanity may be in the throes of an all-out existential crisis. What’s more, the way we currently treat these mental health issues isn’t working. Antidepressants work less than 50% of the time, and people on these drugs are 2.5 times more likely to attempt suicide.

All of this makes one thing clear: when it comes to mental health, we are in desperate need of a new standard of care. Although it may sound like a high-handed statement, psychedelics could be a big part of the solution. On top of a lot of other promising research, a recent study of 27 people with major depressive disorder found that psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy worked far better than standard antidepressants. Another researcher studying the efficacy of psychedelics compared to pharmaceuticals for depression even went so far as to call their preliminary results “game-changing.”

Seeding a social movement

That’s the good news. The bad news is, getting this game-changing care into the hands (or minds) of everyone in need is still a ways off. Which is why it’s more important than ever that microdosing gain widespread acceptance. While microdosing has been studied far less than “full” doses of psychedelics, some research does support the anecdotal claims of their efficacy. A study from the University of Bergen, for instance, found that the 21 male respondents reported improved mood, cognition, and creativity, and that these effects relieved symptoms of anxiety and depression. Another study from the Dutch Psychedelic Society found that microdosing psilocybin truffles could potentially enhance creativity, and yet another found that microdosing increased reported psychological functioning and decreased reported levels of depression and stress.

This isn’t just to show what microdosing can do though; it’s about getting scientific proof that proponents of the practice are not just looking for an excuse to be high all day, but are looking for true mental and spiritual wellbeing. After all, like CBD, the idea with microdosing is to not feel the effects of the drug, but rather the abatement of negative or unwanted feelings. And much like CBD opened the door to the widespread legalization of both medical and recreational cannabis, microdosing could lay the groundwork for widespread acceptance of psychedelic use.

It’s important to exhibit some caution here. Though many people have high hopes for microdosing, researchers have yet to prove out the myriad of claims being made about its life-changing efficacy—and we still don’t know the long-term side-effects, good or bad. It’s also speculative to say that microdosing will trigger a paradigm shift in how psychedelic use is perceived by mainstream culture. We just don’t know yet.

That said, the more of a grassroots groundswell there is, the less solid ground those interested in stamping out psychedelics altogether have to stand on. With more people touting the benefits of microdosing and pushing to end prohibition, the more pressure there is on the powers that be to make lasting change.