The World’s Biggest Medicine Cabinet: Psychedelics of the Amazon Rainforest

LISTEN ON:

Episode 134

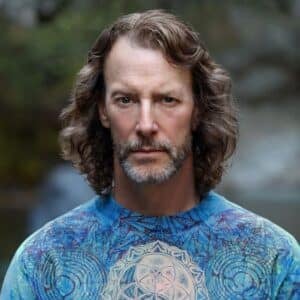

Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.D.

When Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.D. first stepped into a night class with Harvard ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes, the path of his life was instantly set. Almost 40 years later, Mark has participated in close to 100 ayahuasca ceremonies with Amazonian shamans, sampled numerous psychedelic plants from the rainforest, and partnered with multiple indigenous tribes to protect their lands and ecosystem. In this episode of the Third Wave podcast, Mark and Paul discuss Mark’s storied career, the importance of indigenous reciprocity and conservation, current and potential surprising uses for psilocybin, the crucial element of context when working with psychedelics, and more.

Mark Plotkin, Ph.D., was educated at Harvard, Yale, and Tufts and was one of the legendary Richard Schultes’ last students. Mark is an ethnobotanist who has worked from Mexico to Argentina, but specializes in the tribal groups of the northern Amazon. He serves as President of the Amazon Conservation Team, which has partnered with 55 tribes to improve protection of over 90 million acres of ancestral rainforest. His most recent book is The Amazon – What Everyone Needs to Know, and his podcast series is “Plants of the Gods: Hallucinogens, Healing, Culture and Conservation.”

This episode is brought to you by Athletic Greens, the daily drink for a healthier you. Whether you’re looking for peak performance or better overall health, Athletic Greens makes investing in your energy, immunity, and gut health simple, tasty, and efficient. With 75 vitamins, minerals, whole food source ingredients, green superfood blend, and more, Athletic Greens fills the nutritional gaps in your diet and improves energy, focus, and mood. Right now, they’re offering a free one-year supply of vitamin D and five free travel packs with your first purchase. Just go to athleticgreens.com/thirdwave and start making a daily commitment to your health.

This podcast is brought to you by Third Wave’s Mushroom Grow Kit.The biggest problem for anyone starting to explore the magical world of mushrooms is consistent access from reputable sources. That’s why we’ve been working on a simple, elegant (and legal!) solution for the past several months. Third Wave Mushroom Grow Kit and Course has the tools you need to grow mushrooms along with an in-depth guide to finding spores.

Podcast Highlights

- How one class with legendary ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes changed Mark’s life.

- How Mark defines “ethnobotany”.

- What is “indigenous reciprocity”?

- New research on treating asthma with psychedelics.

- The Amazon Conservation Team and how it serves indigenous people.

- Why psychedelic healing isn’t as simple as getting the compounds from the Amazon and bringing them to the lab.

- What possibly accounts for Compass Pathways’ middling psilocybin study results.

- Mark’s biggest quarrel with Timothy Leary.

- The importance of context when using plant medicines.

- Do indigenous people microdose?

- The Amazon as “the world’s biggest medicine cabinet”.

- The importance of biocultural conservation.

- What inspired Mark’s podcast, Plants of the Gods.

- Mark’s own story with psychedelics as a child of the 60s.

- The three biggest standouts from Mark’s 40-year career.

- Mark’s view of the best-case scenario for the future of psychedelics.

Show Links

- Richard Evans Schultes

- Oakes Ames

- Weston La Barre

- E.O Wilson

- Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice: An Ethnobotanist Searches for New Medicines in the Amazon Rain Forest by Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.D.

- Charles D. Nichols, Ph.D.

- The Amazon Conservation Team

- Paul Stamets

- Albert Hofmann

- James Fadiman

- “Could the Amazon Save Your Life?”

- Plants of the Gods,

- Plants of the Gods: Their Sacred, Healing, and Hallucinogenic Powers by Richard Evans Schultes, Albert Hofmann, and Christian Rätsch

- María Sabina

- The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion with No Name by Brian Muraresku

- How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence by Michael Pollan

- The Amazon: What Everyone Needs to Know by Mark J. Plotkin, Ph.D.

Podcast Transcript

0:00:00.0 Mark J. Plotkin: If you don't think altering your consciousness is part of human nature, then why do 5-year-olds spin in a circle till they fall over, okay? Why do seven-year-olds hyper-ventilate until they start seeing stuff? So this idea that, okay, a certain segment of the population wants to go off to the Amazon and have hallucinogenic snuff blown up their nose. Okay count me in. But...

0:00:22.5 Paul Austin: Is that the Yopo? That's the Yopo, right?

0:00:24.5 MP: We're a little branch on the evolutionary tree is not true. All people everywhere have had an interest in altering their consciousness for therapeutic purposes, for inspiration, or for boredom.

0:00:42.3 PA: Hey, listeners, and welcome back to Third Wave's podcast. I'm your host, Paul Austin, here with another episode on this third wave of psychedelics, and today we have Mark Plotkin... Dr. Mark Plotkin, who will join us. Dr. Mark Plotkin is a renowned ethnobotanist who had studied traditional indigenous plant use with elder shamans of Central and South America for much of the past 30 years. He wrote a book, which I have read called, "The Tales of a Shaman's apprentice" in 1994, and has really been one of the foremost thought leaders and researchers on the use of plant medicines specific to the Amazon, so I wanted to bring him on the show today to talk about all things ethnobotany, to hear a little bit about his background and story, and then hear his thoughts and perspectives on this current psychedelic Renaissance that we find ourselves in, so... Mark, thank you so much for joining us for the show.

0:01:37.9 MP: Paul, great to be here.

0:01:40.1 PA: So one of your mentors, probably your foremost mentor was Richard Evans Schultes, who... You sent over a number of resources on beforehand. You know, I heard of Schultes when I read "Plants of the Gods" many, many years ago as I was starting to get into this space, and he's really been a godfather in terms of... To people like you, to Terence and Dennis McKenna, to a number of ethno-botanists that have helped to... Wade Davis as well, that have helped to pioneer the ethnobotany space, and so I'd love just to open our conversation with your reflections on how you met Richard Evans Schultes, what your relationship was with him, and what were a few key things that you took away from your mentorship and learning from him?

0:02:27.6 MP: Well, I had a close and, essentially, a very unique relationship with Schultes like many other people, from Wade Davis to Andrew Wilde. I just wandered into his classroom and I was hooked right away, and this was actually in a night school class, I was a college dropout at the time and one lecture of Schultes and I saw the path in front of me. So I worked closely with him, I not only took every course he taught, I took several of them several times, that's how rich they were. And for those of your listeners who aren't very familiar with it, and I'm sure everybody is to some degree, Schultes was a work study student in Harvard in the early '30s, mid-'30s and did such an excellent paper on peyote that his mentor, Oakes Ames, who was a director of the Botanical Museum, which Schultes later took over, sent him to Oklahoma to study peyote firsthand. Now, Schultes was a poor kid from East Boston, and he said to me at the time, everything west of the Hudson was Indian country, literally.

0:03:32.7 MP: So climbing into a used beat-up old Studebaker with a graduate student named Weston La Barre, who then became... Eventually went on to become a great anthropologist in his own right, after a night in that Tee Pee taking peyote with members of the Kiowa tribe of the Native American church, he was lost to medical school forever, not to medicine, to medical school. He then followed up on a hunch in a clue he found in a herbarium and solved the mystery of the magic mushrooms. Nobody knew they were magic mushrooms in the new world. There were certainly indications on amanita muscaria, which had long been known, but the idea of hallucinogenic mushrooms was something new to people though many people disbelieved it, and he went down to Oaxaca and found them. So what this means Paul, is that by the age of 26, Schultes had brought mescaline and psilocybin to the outside world. That's a feat that has never been equaled and never will be equaled by any other scientist going forward, despite all the interest and money pouring into the field. He then went to the Amazon for six months, went native for 14 years, and discovered ayahuasca.

0:04:40.9 PA: 14 years?

0:04:41.8 MP: Yes, 14 years. And as Schultes is quick to say, "Ethnobotanists don't discover anything, it's really our indigenous teachers and mentors and guides who teach it to us." So he never used the term discover, these days quite a loaded term, but I think it works well, in terms of describing. From a Western perspective, it was certainly essentially a discovery. One other aspect of Schultes' work with mind-altering plants, which is really overlooked, was he did fundamental work on cannabis as well. You don't see this in many of the biographies. In 1971, he went to Afghanistan, to try and figure out what was what. At the time, guys like me in high school, in college, were smoking what we called 'Rat weed', and that was pretty apt description of it's lack of potency, and then there was the really cool hard to get expensive stuff, which we called 'Thai stick'. Well, Schultes figured that out Cannabis... The rat weed was cannabis sativa, and Thai stick was cannabis indica, and then you had this weirdo species, cannabis ruderalis.

0:05:46.0 MP: Now in an age where everybody's crossing everything all the time and coming up with all these crazy and powerful mixtures, it's really hard to sort out the taxonomy, but I think that the work that he did really laid out that there were three lines of origin. So this is yet another aspect of Schultes' career, which is really overlooked by the whole psychedelic psycanoc community.

0:06:07.6 PA: So he helped to amplify mescaline, which was being used really since probably the late... Or known about somewhat, since the late 19th century, and I read the little piece that you would send over before our podcast, how he picked the shortest book in the library thinking it would be an easy task, and then turned out it was mescaline, and his teacher said, "Well, you gotta go experience this", so like you said, he went down to Oklahoma to experience that, went to Oaxaca, found the psilocybin mushroom, spent 14 years in the Amazon to find ayahuasca, then went over to Afghanistan to find cannabis.

0:06:42.0 PA: I'm curious, where does your story then... You mentioned that you were at Harvard and you did an undergrad class with them. How are you inspired then through the work that he had done to pursue your own career in Ethnobotany, and how did that start to trickle?

0:06:55.9 MP: I think it's important to point out that Schultes really inspired a lot of people, not just people who are drinking lots of ayahuasca these days. You know, E.O Wilson, the greatest biologist of our time, describe Schultes, as a personal hero. Dan Goldman, who wrote important work on psychology, described him as an inspiration. So that Schultes is as a persona in some ways was as large as Schultes as a person. And just to finish off on your earlier question, I went off took Forestry school after I finished my degree at Harvard, the night school. I spent two years at Yale, Schultes always referred to that as slumming. And then I came back and worked at the museum as a Research Associate directly with him. And when I was deciding to move down to Washington to work for the World Wildlife Fund, and had to give up my apartment, Schultes said, "Just move into my attic. I'm an empty nester. My wife and I have a big old house." So I actually lived with him for six or eight months.

0:07:50.9 MP: And the reason I mention that is, we spent a lot of time sitting in front of the fire place in the New England winter, drinking scotch, listening to tales that didn't show up in the Botanical Museum leaflets of Harvard University. So when I say that I had this unique relationship with the man, it wasn't that I you know, took most of his classes or hung around with him more. It's just that I saw him in different settings. So that as a mentor, I mean would put him up there with the great archetypes like Merlin or Obi-Wan Kenobi, except he was a real living, breathing human. And the other point I wanna make is that Schultes was at the epitome of academia. I mean a tenured professor at Harvard, publisher of hundreds of papers, yada yada yada. But he was also one of the funniest people I've ever met. He just had this unbelievably hilarious drone manner. Which I'm convinced was one of the secrets to making friends with people. Whether they were in academia or Indians living in the Amazon.

0:08:51.3 MP: Which was, I think part of the secret, part of the key to his success in building these relationships, because Ethnobotany is all about relationships. It doesn't matter how much money you have, or what degrees you have, or how interested you are. You can't just show up and say, You know, "Fork up... Fork over a cool admixture of ayahuasca, teach me how to cure cancer because I gotta get back on campus in a week." It doesn't work that way.

0:09:15.7 PA: It does not... How would you define Ethnobotany then as a practice or as a profession?

0:09:22.2 MP: I think my description is a bit broader than some people think of Ethnobotany is, searching for medicinal plants in the Amazon, following the Shaman with your plant press... Hey, I'm cool with that. But I think that's a narrow definition. To me Ethnobotany is people and plants, the study of all people and all plants is Ethnobotany. You know, if you're studying a farmer in a cornfield in Iowa, that to me is Ethnobotany. Some people would say that's Economic Botany because that's the study of plants that have economic value, so I think that Ethnobotany is a much broader canvas and that Economic Botany fits within there rather than vice versa.

0:10:06.6 PA: And Ethnobotany... I know this podcast in particular, we'll talk a lot about psychedelic plant medicine because that's what we focused on. But Ethnobotany is very broad. It's all types of medicines in all types of ways and how those interact with the local indigenous population. That's pretty accurate, correct? It's very expansive.

0:10:26.7 MP: Well, let me tell you a story, an example of why it's important to have these relationships and to be focusing on the plants. Because nobody... When I got there 30 years ago, 40 years ago, nobody was going to indigenous peoples and saying, "Teach me." Okay, so that was a really different dynamic that created an immediate relationship. But 35 years after I was working with some of these people, we're sitting around and I mentioned that indigenous peoples to the far west 3,000 miles away in Peru used the hallucinogenic frog. And they said, "Oh, we do that here," and it turned out to be the same frog. And then they showed me a new hallucinogenic frog, which has never been reported in literature. Now, this is 38 years of friendship and partnership before they essentially coughed up some new information on a mind-altering creature.

0:11:15.4 MP: And the point I wanna make here, Paul, is that you know, this whole idea... Like when we went to Amazon and we got ayahuasca, and we went to Oaxaca and we get mushrooms, we're done. I totally reject. There's more out there, and the more we look, the more we find. The irony that here we are in the Psychedelic Renaissance, celebrating peyote cactus, celebrating magical frogs, but we're destroying these organisms and these cultures faster than ever at the very same time.

0:11:43.3 PA: Right, and there's a phrase that's often used now, which is 'indigenous reciprocity.' What does that phrase mean to you and all the work that you've done in indigenous reciprocity over the last 40 years? In particular as it relates... 'cause this is something you wrote about in the Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice, quite a bit. Right? In the '70s and '80s, there were a lot of western companies that went down, took out plants or medicines and then created them into molecules to profit from them without properly acknowledging where it came from. So I'm just curious, your perspective on that?

0:12:20.1 MP: I'll give you a real easy translation of indigenous reciprocity. Good manners. You want people to help you, why shouldn't you be helping them? And the idea that just give us the plant to cure AIDS and we'll be back in 16 years with a billion dollars. That's no longer an acceptable way of doing business. And I will say that most of the big monies were made from medicinal plants were in the distant past. Not recently, okay. So the Psychedelic Renaissance in a big way is about the rediscovery of natural products. And one of the things that fascinates me and I'm spending a lot of time on, is this whole issue of psychedelics for therapeutic purposes that have nothing to do with their psychedelic aspects. And in a broad sense it matches what I know you spent a lot of time on... In terms of micro-dosing, here's a concrete example.

0:13:07.1 MP: Charles Nichols in New Orleans, my hometown, has been studying the effect of tiny amounts of psychedelics in treating asthma very successfully. Okay, so the idea is that, well, yes, we know that these affect the human mind and psyche and spirit, and we can sometimes cure things that Western medicine cannot, but guess what? These chemicals can sometimes have a positive therapeutic effect on things that have nothing to do with your psyche, okay. And that's what makes this endlessly fascinating, and I'm frustrated when I see this reductionist approach like... I need to take Ayahuasca 90 times and discover the secret of life. While the rain forest is burning down, you're missing the point. Okay, when I hear people taking... Oh, I took Ayahuasca and I figured out Bitcoin, like really? That's what you did with this sacred sacred knowledge, I mean... Good, I guess. That wouldn't be at the top of my priority list in terms of what we're using these things for.

0:14:05.6 MP: So the point I'm trying to make here Paul is that all of us who're interested in these products, natural products, semi synthetic products, synthetic products, should be using it to appreciate the oneness of life, the interconnectedness of butterfly effect, which is something we all come away... Come away with. But how do you put that into practice? And that goes back to your question about indigenous reciprocity, how can you help indigenous peoples or peasant peoples or Afro-Amazonians make a better life? It's not all about the money. One of the most important things my organization, the Amazon conservation team has done, is partnered with indigenous peoples and peasant peoples to map their lands. And we map it, we manage it, we protect it much better as a result of the maps, but we don't make the maps. Okay, it'd be easy for me to make a map and hand it to 'em. It's much more important and much more impactful to teach them how to make the map, so they can take charge of their cultural environmental destiny. So these types of partnerships shouldn't just be about, can they give me something to make me trip? And then I give them a few bucks. But how can we help these people?

0:15:10.2 MP: Everybody out there in podcast land knows more about making websites than I do... Every tribe on the planet should have it's own website. And these types of things, and ways that we can all help these people without saying, "Okay, let me find the cure for COVID, and then I'm gonna give you guys millions and millions of bucks." That's a magic bullet approach. I'm a much more bigger believer in a magic shot gun approach. What can we do now immediately without involving millions of dollars or waiting decades to be able to help these people protect their culture, their land, their forest, their rivers and deal with the outside world better on their own terms rather than white guys like you and me deciding what they should or shouldn't do.

0:15:56.8 PA: Right. There was a situation several years ago in the psychedelic space, I think even before I got involved, I got involved around 2015, and it maybe happened in 2013 or 2014. Where there was a group that tried to go down to the Amazon and something with Ayahuasca and something with... They were gonna set up a relationship with local shamans and try to pay them, but it all went very sideways very quick, because again, it was these white people who are going in who are trying to tell indigenous people what to do and the whole thing ended up-blowing up. And I think that speaks to, like you said, the sense of having manners, the sense of... And you, I mean... The name of your book represents this. Tales of a Shaman Apprentice, you went down, you apprenticed under someone who had been doing this for years, if not generations, if not many, many generations through their lineage. And you said, "Hey, I'm here to learn. I'm here to be a steward and witness and observe, unfortunately, the sort of fading out of the indigenous way of being."

0:17:03.7 PA: I think you mentioned at the end of the book that by the late '80s, early '90s, western clothes, Western radios, western food was all starting to come in and you were witnessing how that was destroying some of that knowledge and wisdom. And yet here we are now in a globalized world where we have to figure out how do we live in harmony with these groups, and I think what you're talking to... It hits the nail on the head because you're saying, we're not gonna tell them... Build a map for them, we're gonna empower them so that they feel like they have the capacity to do what it is that needs to be done.

0:17:36.3 MP: Well, let me give you a concrete example, based on what you just said. I got a call from a guy saying, "Well, I'm putting together this consortium with these guys who're starting a psilocybin company, and we wanna help the indigenous peoples and we wanna give back, yadda yadda yadda." And I need to know how to do that. And I said, "Well, you know, it's very difficult. I've spent decades, and I've made a lot of mistakes and I've learned a lot of lessons." And he said, "Okay, so how do you do it?" And I said, "Yeah, it's very difficult. It's hard to learn. It's hard to do it right. There's a lot of pitfalls to avoid and he goes, "Yeah, yeah. But how do you do that?" And I said look... I said, "You sent me an email saying, there's billions of dollars going to your company and you don't even have a product on the market. You want me to tell you what I've spent 40 years learning for free. Okay, I'm not looking to get paid here, I'm not looking for a consultancy, but you say you wanna help the Indians, you know, write the Amazon Conservation Team a check and show your good faith. Because this is like the wimpy approach to sustainable development, I'll gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.

0:18:40.0 MP: And he's like, "Well, I'm just trying to get it so I can help the Indians." I'm just like, "Dude, you're getting paid, but you're not paying the Indians. You're telling us trust you, and in a couple of years there'll be big money. That doesn't work." So the good news is that people are talking this language, the bad news, there's just a lot of bullshit involved. Put the money on the table and show us you're serious rather than using this as a marketing line to pull in more money from investors, how you gonna help the Indians, then you're gonna sell it off and then... And the owners aren't gonna give a shit.

0:19:07.9 PA: Precisely, there's a lot of smoke and mirrors. I was just at a conference this last weekend in Miami. It was like a business medical industry conference, and I'm just someone who's always in the psychedelic space, I've focused on non-medical, non-clinical. I've been really about how can go from clinic to culture, and there's just a lot of buzzwords and a lot of phrases, but at... When you kinda start to dig, it's a lot of emptiness. And I think what we're... What we know from the indigenous use of these compounds, these medicines, sometimes for thousands and thousands of years, we trace back the immortality key, and the Eleusinian Mysteries, and Ayahuasca in the Amazon. There's so much richness and depth there that you can't just sort of... You get the top of the iceberg and actually, you really need to go deep and live and be present and experience that, if you want that to be part of your company. I, myself, we've taken a much more Western approach, it's not necessarily that we do have some reciprocity measures that we've implemented, but I think if that's what you're presenting, then go do the hard work, go spend the time in the Amazon, go spend the time and with the Mazatecs or whatever it might be.

0:20:20.0 MP: I think we're looking at a continuum here. If you look at alkaloids, like the curare alkaloids, which were muscle relaxant, abdominal surgery earlier on, they've been completely replaced by synthetics. Some chemicals, you can collect them that we look at stuff in the herbarium at Kew, outside London, stuff that's been collected over 100 years ago, like the original Ayahuasca alkaloids, are still active. Okay, so an alkaloid, is an alkaloid, is an alkaloid, However, I reject the idea that a physician who took a class on this in medical school can do with psilocybin, what some of the great shamans in a Oaxaca can do after studying it for 60 years. Okay, so it's not either or, but this reduction is like, Let's just get the mushrooms and grow them in the lab, and we can fix everything. No, that's so true. Now, the flip side of that is there aren't enough shamans to go around. Not everybody who's interested in these plants or fungi, or frogs can go down there and take things in a Shamanic setting.

0:21:18.8 MP: That's a given. But the idea that let's just get the chemicals out of the rain forest or a Tundra or the desert or wherever, and put them in the lab, and we can do everything that a shaman can... Trust me, it's not gonna happen. So that you need to have all of this buffet laid out. If you wanna do it right, and instead of this idea like, Okay, I'll start a company and I'll sell psilocybin, and I'll make a bazillion bucks. I'll give the Indians a few pennies. Not acceptable.

0:21:47.2 PA: It's interesting that you're bringing up at this at this point in time. Compass pathways who I'm sure you've heard of, at this point in time, just released their phase 2B trial results, they enrolled 233 people in psilocybin and the results were okay, but the weren't great by any stretch of the imagination. And that's, I think, to your point, it's because when you remove the complexity, when you remove the shamanistic approach, 'cause so much of it is psychosomatic, so much of it is not necessarily purely physiological, but it's, how you prepare? And it's often non-linear. Like you talk about the example of... I was listening to another podcast, your foot hurting for a lot of time, and then you went and saw a shaman and they healed the foot, and if you try to explain how that happened, you couldn't, but yet you were in that context and in that dynamic and something was done to remove that energy, and these are not things that can necessarily be reduced into X, Y, and Z.

0:22:45.9 MP: Here's one of my many quarrels with Tim Leary. He talked about set and setting, and everybody's always citing that. He missed the most important S, shaman. Okay, set setting and shaman, the aspect to ritual, the chanting, the diet, whatever. It's important and even essential in some of the cases, not all of them, but this idea that you just give me the cure for X and I'll go back and I'll give it to people in a syringe or whatever... And we're cool with that. That's too reductionist. You're throwing out the baby with the bath water. There's the famous case of Paul Stamets, who I'm a great fan of, where he took psilocybin and cured his own stuttering. Fantastic, that does happen. That's not a unique case. But the idea that we should all climb a tree in a rain storm and tell ourselves, don't have insomnia, don't have acid reflux, don't be anxious, all this other stuff, that's gonna work in some cases, but not all of them, and I'm not even sure how many. So that it shouldn't be an argument of shaman versus buying the stuff on amazon.com. We should have that buffet in front of us if we really wanna get it right.

0:24:01.3 PA: I'm glad you brought up Timothy Leary because one way that you referred to Richard Evans Schultes was as a trickster, and Timothy Leary had a similar archetype as a trickster, so to say. They both were at Harvard, they both were very well established academically, and yet the way I would say, of course, Timothy Leary is much well-known culturally than Richard Evans Schultes, to some degree, but I'm curious from your perspective, both are tricksters. What's the difference? Why was Schultes who he was and why was Leary who he was and what was the gap between them?

0:24:37.7 MP: Well, I never met the Leary, so I can't comment on him in the same perspective as I can with Schultes. When I say Schultes was a trickster I mean that in the most positive shamanic sense. He was a guy who looked like the most conservative nerd in Harvard Square. Always wore a white lab coat, always wore a Harvard tie, always had his wire rimmed spectacles, but he was the original wild man. Doing all of the stuff in a tribal setting. Many of the time we'd be walking across the Harvard Square chewing epadu, this cocoa powder from the Colombian Amazon. I remember once he was walking back from Harvard Square to the museum, which is just north of the square, and this is at the height of the drug hysteria, and one of the Deans said, "Hello, Richard, how was your last trip to the Amazon?"

0:25:20.3 MP: And Schultes said, Oh it was great, we found a new hallucinogen," which was the last thing a Harvard guy, a Harvard Dean wanted to hear, but this is how he was. Another time... He used to love to go to these Nobel prize receptions, 'cause so many Harvard Profs would win Nobel prizers, and he would always go up and say stuff like, Well, Brian... Congratulations. And the accolade fellows would say, Thank you Richard. And Schultes would say, You know Brian, by my tally, there's about 12 or 13 Harvard professors who have won Nobel Prizes, but there's only one that had a genus of Amazonian cockroach named after him.

0:25:54.1 MP: So this is who he was. Where is Larry is a trickster. I'm not sure. I think I would use trickster differently with him, the man started some very important research with convicts, with religious leaders. That type of work is being replicated today, but they just kinda went off the rails by my reading of it, that they lost the scientific approach, which is necessary for gaining respect in Western circles as we're doing now, and I think that some of this over-emphasis and sensationalism really set the field back many, many decades, and fortunately, we live at a time where we're realizing the value of what these indigenous peoples told us long ago, what Schultes was saying all along, so it's both gratifying and frustrating that we lost so much time.

0:26:42.7 PA: Well I might in just in talking about this. What's coming over me is it seems like Schultz understood that these medicines had a context, right, so when they were used in the Amazon, there was a very specific context that they were used within, and Leary took a much more evangelical sort of let's just give everyone acid approach without really honoring sort of the lineage and the context in which it was done, and so both recognized the potential and power of these plants of the Gods, so to say. But it feels like Schultes understood boundaries. Right when he was at Harvard, he was a Harvard man. He wore the white coat as he needed to, he cracked the jokes that felt appropriate, and when he was in the Amazon, he was the wild man, participated in being with that. It seems like with Leary, it was just a little more about Leary rather than about the healing or the medicine itself.

0:27:36.1 MP: I think that Schultes took a much longer term approach, and I like to think that our organization, the Amazon Conservation Team, is continuing his legacy for trying to protect these traditions and trying to protect these forests, rather than saying. Well, I could make a bunch of money or get a bunch of attention by giving the world ayahuasca or psilocybin, or who knows what we'll find next, and I think that that's a much more respectful approach in terms of the cultures that give birth to it, and that the idea that you should be doing ayahuasca in a long house with an ayahuasca Shaman is the right way to capture the real magic and therapeutic aspects of it. I mean, this is something that I don't think many people have access to, certainly, I don't know that Leary ever did this with the real traditional healer, even though he took mushrooms for the first time in Cuernavaca it's in Mexico, but it's suburban, Mexico City it's not Oaxaca.

0:28:31.9 PA: And it was at a resort with eight white friends, I remember reading the stories about it.

0:28:36.0 MP: Yeah.

0:28:36.0 PA: So it wasn't with a Mazatec or anything like that, like Gordon Watson did.

0:28:42.0 MP: But there's one aspect of this, which I find that very few people interested in these subjects realize which is that beta-blockers, to a large degree, were inspired by compounds and the magic mushrooms, and they were developed by Albert Hofman, which was the name I'm sure familiar to many of you guys. So this goes back to the point that I made earlier, and in response to your question, which is that there are other applications that don't have to do with the psychedelic aspects of this. These are chemicals which have a strong effect on the human body, and that if we're just looking at the psychedelic aspects, anxiogenic aspects, I think we're once again sort of selling them short of literally in some cases.

0:29:29.2 PA: Let's go into that a little bit in terms of microdosing. Is that something that's used by those who have been using this in the Amazon, those who have use this in Mexico. Is microdosing a thing whatsoever for performance or for hunting or for?

0:29:44.5 MP: I've never seen, I've never heard.

0:29:45.6 PA: You haven't.

0:29:46.5 MP: But you know what that means. That means I've never seen it, and I've never heard of it. Ethnobotanists do not say indigenous peoples don't do that, or Indigenous people, if you'd have asked me 30 years ago if Indigenous Peoples took hallucinogenic frogs, I would have thought you were hallucinating, so this is why you say I haven't seen it rather than it doesn't exist. I don't suspect that it, that exists, but one learns in this field never to say never. However, I'm intrigued to tie in this whole microdose idea to this work this fellow is doing in New Orleans, which I think you can make the case is kinda micro-dosing and proving it has therapeutic effects even though it's not what you're looking for. So I suspect that micro-dosing is like a Pandora's box in a good way. Where which we're just gonna keep finding new and useful aspects to it, which may or may not have to do with anxiety or depression or focus, and may have some very valuable aspects for things we weren't even looking for in the first place, which brings me to another point Paul.

0:30:40.7 MP: We all know that Quinine was the first effective drug for treating and curing malaria, but in the '50s, when malaria was common in this country, that many people taking a quinine bark or quinine bark aspects had their cardiac arrhythmias cured, and that was because it turns out there was another alkaloid in the bark called quinolone, which wasn't a malaria fighter, and that this was used to treat malaria and they were curing something else with it, and I think that's probably gonna be a predictive analogy for what we're gonna find, with things like microdosing, where we do a different approaches, even then the indigenous peoples know were used and find out their additional therapeutic applications. So that's why I find it frustrating when people just wanna talk about Ayahuasca, just wanna talk about psilocybin, just wanna talk about LSD when they're missing the point that there's more stuff out there. I'm convinced more stuff out there, we'll find more stuff out there, and the more stuff out there that we can find and protect and honor and reciprocate, the better off we'll be.

0:31:47.7 PA: I did an interview with James Fadiman, I don't know if you know of James...

0:31:50.8 MP: Of course.

0:31:52.4 PA: Who wrote The Psychedelic Explorer's Guide, eight or nine months ago. And the point that he brought up was, microdosing is like the AM dial and high doses are like the FM dial, you're still tuning into the same transmission, you're just getting a slightly different interpretation, and he compared microdosing to aspirin right?

0:32:11.5 PA: Where aspirin, when it was discovered many, many years ago, it was only at these higher doses. But what they found out is if you took very little doses more consistently that it could help with heart issues. And so all of a sudden, this new way of working with aspirin opened up. And it feels like microdosing is... Like you mentioned the work of Dr. Nichols at LSU. He's looking at the anti-inflammatory properties. So, how does it help with the central nervous system? What's the relationship of microdosing to the gut, in the serotonin in the gut? And now that could open a new pathway for dementia, for asthma, for all of these inflammatory issues that previously we had no context for necessarily.

0:32:49.8 MP: Exactly. And again, another point to make with all of these medicines, natural, synthetic, semi-synthetic, is that there's still diseases that will come up that we don't know. I mean, if we'd had done this interview five years ago, you would not have asked me what indigenous peoples use for COVID, right? And the idea that COVID is the be-all and end-all is nonsense, okay. So I mean, 30 years ago, people were all about AIDS, treatments for AIDS. So again, we have to not only find treatments for new diseases, we need better treatments for existing diseases. I mean, there are treatments for depression. And they're very effective in some cases but not in many, which is why microdosing or even macrodosing provides new answers. So again, it argues for the need to keep looking, keep experimenting, keep working in the lab, keep working with the shamans, keep protecting forests, quarries, wherever. But we can't just figure that, "Okay, we got this good stuff, and we can close the door and not worry about the poor rainforest," and just figure, "Well, we've got everything that's out there to get." It's absolutely not true.

0:33:56.7 PA: I kinda wanna open that up, right? Because one of the phrases that you've used is that the Amazon is the world's biggest medicine cabinet. And I'd love for you to just talk a little bit about that and sort of expand on that.

0:34:08.3 MP: It's a basic ecological theory that as you move towards the equator, you get more and more species. That's why rainforests are so rich. And because they're so rich, there is an ongoing battle between organisms. I mean remember, plants can't run away, so they have to evolve chemicals to fight back. There's tens of millions of insects that live in the rainforest, and fungi as well that are very poorly known, very poorly studied. But that doesn't mean that the local plants can afford to not worry about it. The rubber tree didn't evolve rubber to make the Industrial Revolution possible, which it did. It did it to gum up the mouth parts of insects that were trying to chew on the bark. So that if you wanna look for places where you're gonna find new things, you need to find where the diversity is.

0:34:52.9 MP: Now, this is not to argue that all of the great new drugs are in the rainforest. It's not true. It's just there's likely to be more of them because there's more species, there's more chemical warfare, there's more alkaloids. I mean, if you look at the way that we are able to do surgery where immunosuppression is very important, like organ transplants, that comes from a fungus that comes from, I think, Norway originally. So this shows you that it's not all about the equator. However, there's just more there. And I would never argue that we need to protect the rainforest and to hell with everything else. No. It's all connected. But that it just makes sense, from what we know, that there's gonna be more potential there. And let's face it, there's more species threatened in the Amazon or in the Congo than there is in Austin, Texas or Arlington, Virginia.

0:35:43.6 PA: Right. And unfortunately, it's now burning, right? You wrote the op-ed for New York Times, which we'll link to in the show notes, about precisely that. How that relates to... I think this is in the COVID era as well. And it's devastating because when the world's biggest medicine cabinet is burning, we're losing all these potential medicines that could be helpful for diseases that we're aware of or even that we're not yet aware of, which is too bad.

0:36:09.9 MP: Well, when you look at how much information is coming out on psychedelics, not a week goes by there isn't some major article in a place like the Wall Street Journal [Unclear speech] talking about spiritual experiences from taking mushrooms. Who knew? Very seldom is there any emphasis or even a mention about how important it is to protect everything else that we don't know, which is common sense. So that, to me, is very frustrating. And again, when people say to me, "Well, the Amazon, it's really getting hammered. Is the glass half full or half empty?" Well, any glass that's half full is half empty. It's half full. We have all this interest that we didn't have 20 years ago. But it's half empty because we're burning it faster than ever. So that is my frustration. And this is why we at the Amazon Conservation Team do what we call bio-cultural conservation.

0:37:00.6 MP: I mean, you went in Schultes' office. There were two pictures right behind him. One was two indigenous members of the Yukuna tribe snuffing during a ceremony. And the other was Chiribiquete, which is the largest rainforest park in the world. So it was nature and it was culture, and they weren't separated, okay? So all this emphasis on new medicines from nature, or even old medicines from nature, there needs more emphasis on new potential medicines from nature and the people who are gonna teach them to us. I can't think of any major hallucinogen, natural hallucinogen, that was discovered in a laboratory. I mean, you had people like Sasha Shulgin creating them. But for the most part, they were based on natural models. And the more natural compounds we have, the more we can use technology to create semi-synthetic or even synthetic ones based on the natural stuff. I mean, that's what beta blockers are, right? They're inspired by stuff in the mushrooms, even though there were no beta blockers in the mushrooms themselves.

0:37:56.0 PA: There are still probably dozens of hallucinogenic plants that we don't know of, that we haven't found.

0:38:03.7 MP: Could be more, could be less. But you know what? Let's protect all the pieces and find out.

0:38:07.8 PA: Exactly. Well, let's get into that a little bit. Plants the Gods. This is a new podcast that you've launched in the last year or so, I believe.

0:38:15.7 MP: Yeah, about a year and a half.

0:38:15.9 PA: And I'd love for you to tell our listeners a little bit about what inspired that initiative. And what is it that you cover in Plants the Gods generally?

0:38:23.3 MP: Well, the obvious answer is it was inspired by Schultes' book, which to me is the most impactful book I ever read Schultes and Hofmann, Plants of the Gods. Which talked about how these antigenic plants and fungi were literally the basis of a lot of aspects of Western civilization, religion, art, music. And I just think most people don't look at the world through the lens of how it was impacted by these sacred plants and mushrooms. And that book laid it out. So I wanted to do a podcast. There's lots of excellent podcasts. There's yours, there's Joe Moore's.

0:39:00.1 MP: There's a lot that really aren't so good, but that's okay, that's a great thing about podcasts, anybody can have a voice. But I thought, if I'm gonna do something, I wanna do something different. And because I'm an ethnobotanist and because I've had the honor and privilege of going through so many ceremonies with these indigenous peoples in Oaxaca, in the Amazon. My perspective compared to the other podcasters I've listen into, is fairly different. And the idea is not to replace anybody, the idea is to be complimentary. Your perspective compliments mine and that's what I'm trying to do. I don't wanna reinvent the wheel. I want to invent a new wheel, which fits on the wagon with all the other wheels. And by virtue of the fact that I was one of Schultes last students, again, I think weaving in his legacy and to talk about what he contributed and why it's important is part of my mission here.

0:39:51.0 PA: What are your three favorite episodes so far that you've had a chance to record for that? I listened to the one that you sent over, which was about Wasson and Hoffman and which I loved, was... It's when you talk about the beta blockers, which I had no idea.

0:40:07.5 MP: The holy trinity of ethno-mycology.

0:40:10.3 PA: Yeah.

0:40:11.3 MP: And the holy trinity is Schultes, who first discovered the mushroom from a western standpoint, Wasson who followed up and did much more on that, who then brought in Hoffman who isolated and then synthesized psilocybin. So that was undeniably a major advancement for world civilization. However, there were two people left out of that Holy Trinity, and that is Wasson's wife. Wasson's wife was a physician and any ethnobotanist worth her, his salt knows you need to be talking to doctors just to get a fuller perspective. The doctor cannot do what we do, but it's always useful to have a professional alongside, as well as anthropologists and linguists, so I'm not just all about doctors, but she was a physician. So she's never really gotten the credit I thought she deserved in terms of the medical aspects of this whole story. Second is Maria Sabina.

0:41:04.6 MP: Maria Sabina was the shaman who gave the mushrooms to the Wassons, and how can you talk about a Holy Trinity and not have Mother Mary essentially being part of it? So that was a very popular episode, the most popular ironically is the life and times of Richard Schultes, and then one of my favorites is Plants of the Apes, how animals, particularly monkeys and other apes are using plants for medicinal purposes, everything from anti-infectives to contraceptives. It's a very cool story. And when I asked my mentors, the shamans, where they learn these plans, they say, we learn them in dreams, we learn them when we take hallucinogens and we learn them by watching the animals. So that... I'm trying to expand it. Here's one thing I've done with the plants the Gods that's very different. Schultes and other people who write about hallucinogens or have written about hallucinogens do not talk about liquor for the most part.

0:42:07.3 MP: So I did one on the Ethnobotany of Wine. Wine is the most important plant product in the evolution of human culture, except for the cereal grains and corn. If you look at the Romans, and that was a central part of the culture. Tacitus, the poet laureate said no poem was ever written by a drinker of water. So if one of the reasons we're celebrating these substances is because they alter the mind, they alter the mood, they lift depression, they inspire us to sing and dance and write poetry, why not include alcohol. It has to be part of the story. And so, in that sense, I'm trying to amplify their perspective to saying that anything that manipulates or changes your consciousness needs to be considered part of this, this movement, this renaissance. And Andrew Weil... And people know Andrew Weil was this guru who brought alternative medicine to the fore, but what very few people realize, he was a Schultes student.

0:43:04.7 MP: He was an undergraduate student of Schultes and it was Schultes who had put him on that path even though he went off to medical school. And Weil wrote in one of his first books, that if you don't think altering your consciousness is part of human nature, then do five-year-olds spin in a circle till they fall over? Why do seven-year-olds hyper-ventilate until they start seeing stuff? So this idea that, okay, a certain segment of the population wants to go off to the Amazon and have hallucinogens snuff, blowing up their nose okay, count me in, But...

0:43:35.0 PA: Is that the Yopo? That's the Yopo, right?

0:43:37.1 MP: [Overlapping speech] weird little branch on the evolutionary tree is not true, all people everywhere have had an interest in altering their consciousness for therapeutic purposes, for inspiration or for boredom.

0:43:52.8 PA: All valuable and viable reasons from my perspective. And the Immortality Key laid that out, I don't know if you've had a chance. I feel like you've probably heard about it or at least have seen some things as it relates to it, but what was laid out in there is how wine was then infused with Mer and wine was infused with other psychedelic substances and that it's no coincidence that wine was the drug of choice of Dionysus, and then also the drug of choice of Jesus Christ and Christianity, and obviously, so much of what we are as a culture and a society goes back to that. And yet, in the psychedelic space, and I would say I've been somewhat guilty of this as well, I've done my fair share of drinking, and there's a lot of not so nice consequences sometimes if you drink too much, and I think some people see mushrooms or ayahuasca as being more spiritual or being more pure or being more... You don't have a hangover the next day, and yet, I would agree with you that wine with friends is just as, if not a better way to bond and connect and live compared to mushroom. So it's all on a... As you just mentioned before, this is on a continuum in many ways.

0:45:10.3 MP: In my... I did an episode on the Ethnobotany of Wine where I talked about the fact that, yes, alcohol does have a downside and a negative side, so does opium. So do most of these things. And it all needs to be used under supervision, and in the right amount. As Paracelsus 500 years ago said, "The dose makes the poison." If you don't think that's true, eat 500 aspirin, you'll be dead as a doornail. So the idea is how much to do? How much is necessary? How much is right? I've been through many, many, many Ayahuasca ceremonies, probably close to a hundred at this point. And if the Shaman says "Have another cup" I do it. And if he or she says, "No more for you." I don't do it. And, I did a marijuana trilogy for plants of the gods podcast, and I pointed out that if you give five guys all the liquor they want, they'll end up in a fight. If you give five guys all the marijuana they want, they'll end up in a band. [laughter]

0:46:09.1 PA: I love that. [laughter] So, what if you give them all the acid that they want? What happens then?

0:46:15.3 MP: If you give a guy all the liquor he wants he'll be going down the interstate at 105 miles an hour, if you give a guy all the dope he wants, he'll be tearing down the interstate at 15 miles an hour.

0:46:24.3 PA: There you go.

0:46:24.9 MP: So some of these mind altering substances have safety controls built in.

0:46:29.8 PA: Right.

0:46:29.8 MP: But the point is, how can we best use them? What's Western medicine is cure for depression? Doesn't have one. You and I know that there's incredible results coming out from these labs with psilocybin and MDMA. And is this a panacea cure? Of course not. But we're curing some cases, improving many cases that weren't responding to Western treatment. So again, this... Once again, argues that it's not the Shaman versus the doctor. It's the microchip and the medicine man, that offers the best path forward. And that's why wine is a good treatment for depression. In light cases, if you're drinking just enough of it, it doesn't mean you should go out and get trashed and smash and think it's gonna cure any serious problem. But a glass of wine, now they're finding it's therapeutic. Gee, who knew that, except the Romans and the Greeks and the Phoenicians and the Sumerians and everybody else. The first medical prescription written was on a cuneiform tablet from Iraq. So wine...

0:47:38.3 PA: Babylonia? Or Sumeria? Wow. And so, one thing we haven't really touched on a whole lot yet is your own story with these medicines. When did that start for you? I know you were at Harvard in the late '60s, early '70s.

0:47:53.7 MP: Right.

0:47:54.3 PA: Which was sort of within, just after that second wave of psychedelics, just after the counterculture. Was this something that you became interested at in university or was it until you went down to the Amazon that you started to work with hallucinogenics in...

0:48:09.5 MP: I'm a child of the '60s, I grew up in the '60s, I got to Harvard in '74. I grew up in New Orleans, I smoked my share of dope as a teenager. So, this is what people did. It wasn't like it was a realization, it just fell out of the sky or stuff. New Orleans is where marijuana first entered the US. And that is why jazz was invented in New Orleans because it changed musician sense of time. So this was never new to me. And this ethnobotanical explanation for the origin of jazz, why it came from New Orleans. I haven't heard a better explanation. So when I got to Schultes and when I got to Harvard and took Schultes' class and I heard this very staid and solid Harvard professors saying, "Go down there, live with the people, hunt with the people, drink with the people, eat with the people take Ayahuasca with the people." I'm like, "Okay I'm in."

0:49:00.3 MP: So it wasn't like, all of a sudden there was a rapid change of career, I was lost to law school forever. I was interested in exploring, I was open-minded, I was looking for romance and adventure. Who isn't at that age? Just that I found a path I'm still on, I think it's fair to say.

0:49:20.1 PA: How old were you when you went down there? Was this right after university that you made your way to the Amazon, then? Or were you first at the museum and then eventually, found your way down there?

0:49:29.0 MP: I took Schultes' class when I was 19. And that hooked me. And I was working in a museum, the Harvard Museum now known as Harvard Natural Museum. I was working in the branch known as the Comparative Zoology Museum, which was joined to the botanical Museum, which is joined to the Puberty Museum, which is the part that's best known. And I was working as a gopher in the herpetology department and there was a graduate student there named Russ Mittermeier, who was like the Indiana Jones of the time, spoke seven languages went off for years at a time. And he said that he needed some help on an expedition in search of an endangered lizard that nobody had been able to catch. It was a bright blue gigantic lizard.

0:50:06.9 PA: Oh, cool.

0:50:07.0 MP: So I signed on. And I went and we found it and we collected it...

0:50:10.1 PA: You found the lizard?

0:50:10.5 MP: Yeah, we found the lizard, so...

0:50:12.4 PA: What's the name of the lizard?

0:50:14.7 MP: Well, it's a blue Ameiva. Ameiva is a big lizard in Venezuela. It's known as un come huevos, an egg eater. It looks like a cross between... Let's see, how would I describe it? A cross between an iguana and the really badass dinosaurs from Jurassic Park.

0:50:34.4 PA: Wow.

0:50:35.9 MP: Big honkin, a carnivorous lizard. They're about this long, they're a metre long. We're not talking about carrying of small children. But, to a kid who grew up reading dinosaur books this was like landing in the middle of a fantasy. And they're bright blue. Who's ever seen a bright blue lizard?

0:50:52.0 PA: That's cool. Yeah, you expect that with the frogs, but not the big lizards, right?

0:50:57.5 MP: Yeah, yeah.

0:50:58.1 PA: So you're down in the Amazon and then... Ever since then, that was 30, 40... 40 years ago now almost. You've been in and out, you've been... You set up a nonprofit. What's... Kind of just bring us through the trajectory of your career from when you went down and found this big blue Lizard until where you are now?

0:51:17.6 MP: Well, I was down there nominally as a herpetologist, which was to catch lizards, which I did. But I saw the people using all these plans, which I was frankly more interested in, having already taken Schultes' course. But, when you're kid likes a buffet. You got this that look good, that looks cool. This looks interesting. My dad sold shoes for a living, it's not like I followed in the tradition of Plotkin ethnobotanist. And frankly, most people then, unlike many people now, they didn't know what an ethnobotanist is. I just kind of made my way. So I went to forestry school because I wanted practical hands on knowledge. And then I went back to Harvard to work with Schultes, who said, "If you're gonna be a scientist, you need to get a PhD, but I'm stepping down. So why don't you go to Tufts, right next to Harvard, because I can be on your thesis committee, which I can't be at Harvard, because I'm retiring."

0:52:04.0 MP: So I was simultaneously working for the World Wildlife Fund, working at Harvard and going to school at Tufts. And then I got a job at World Wildlife Fund, Schultes had retired, I moved down to DC. I worked with World Wildlife Fund for about eight years. I then went to work for Conservation International, and then I saw that there was an incredible opportunity, and a need in the Amazon, because the best-preserved lands were indigenous lands, but nobody was working with them to help them protect our rainforests and rainforest culture. And that's why my wife and I set up what's called the Amazon Conservation Team, to focus on protecting culture and biology. And that's our origin, and we've had the honor and privilege of partnering with over 100 tribes, 100 South American tribes, to map, manage and improve the protection of 90 million acres of ancestral rainforests. And I've been asked, on more than one occasion, if you're so good, how come I've never heard of you? And it's 'cause I spend all the damn money I raised doing the damn work. We don't do direct mail, we don't put up billboards and all that other stuff. Donors money goes where it's supposed to, which is right into the rainforest.

0:53:09.7 PA: Congratulations, and thank you for that work. 90 million acres and you've been doing this for 20 years, 25 years?

0:53:21.2 MP: No, 38.

0:53:23.7 PA: Wow! And so over the span of that time as you've been tracking climate change and as you've been tracking deforestation, and as you've been tracking the changing ways of life within the Amazon itself, what are three of the biggest things that have stuck with you? The biggest insights or nuggets of wisdom over the trajectory of your career in the past 40 years?

0:53:50.7 MP: Well, I'd say one is that traditions don't disappear so easily. The whole story of magic mushrooms is a complicated one, where the Spaniards recorded it, and they were horrified by it, because these people were so much in touch with their religion. There's a great quote actually about peyote by an anthropologist who said that the white man goes into his church and talks to Jesus. The Native American goes into his church, takes peyote and talks to Jesus. And so, it was believed that this tradition had died out at the end of the conquest with the Inquisition and stuff like that, but old Schultes went down to Oaxaca in 1938 and found out, yes, the tradition survived. It was like down to three tribes, and he was able to find it. I would say that number two, the cultures change over time. The idea that all of these indigenous cultures were just like they were in 1491, and if Columbus had never shown up, they'd all be the same as they were in 1491 is not true. Cultures change over time. And of course, they're changing rapidly now with the homogenization of the world. Many of the shamans I work with now carry cell phones. But that's neither good nor bad. It's both.

0:55:01.8 MP: And we can talk about stuff... I mean COVID is a perfect example. I haven't been in the forest in 14 months, which is the first time in four decades, but I talk to the shamans and some of the tribal leaders on a regular basis. Thank you, WhatsApp. So that... The same technology which can undercut the culture, can also be used to reinforce it. Technology is like a sword. When Columbus first landed on Guanahani Island, which is probably somewhere in the Bahamas, people still debate it, and they said he had pulled out a sword and said, I declare these lands for the king and queen of Spain, the chief of the indigenous tribe reached up and grabbed the sword, because he'd never seen metal before, and it cut him and he bled. And I thought, you know, technology is the same way. It can be used for good, it can be used for bad. So this idea that we just have to give all these indigenous peoples iPads and it's gonna save the culture and rainforest is nonsense. You know what happens when you give guys access to the internet for the first time, you know exactly what they're looking at, and it's not cultural preservation.

0:56:09.2 MP: So one of the things this mapping methodology does is it introduces technology in a way which helps protect the culture and the forest. Helps them record grandfather's medicinal plants, helps them record grandmother's healing songs. So this idea that money or technology or laws is all we need to protect this part of cultural diversity is nonsense. It's not that easy. If it was that easy, it would be done already. There's a saying in Suriname that I dearly love. To every complicated problem, there is an answer, which is both simple and wrong.

0:56:47.0 PA: Yeah. And what's the third?

0:56:49.0 MP: The third thing would be that one of the things that we got wrong with our society is that we don't sweat. Okay? Our lives are all about being in the heat when it's cold out, being in the air conditioning when it's hot out, and we don't sweat. And when you sweat, you're getting rid of those toxins and when you don't sweat, you don't. And sweating is kind of a reductionist thing. The Indians say, "You need to purge," okay? This is part of Ayahuasca, you need to purge, you need to vomit, you need to defecate, and that gets rid of toxins that just sit in your body. And since we never purge... I mean, vomiting is considered something you never wanna do, rather than something that's necessary for good health. So that this whole idea of breathing in clean air and expelling toxins, either through purging or through sweating is, I think, one of the causes of the many ailments we all suffer. That we're too cosseted. If you look at how these indigenous people live, they get more exercise, they drink more water, they sweat more, their feet touch the ground, which ours never do. Your bare feet don't touch the ground. Where do they touch the ground? On the beach, and everybody feels great at the beach, I think there's a connection there.

0:58:05.9 PA: Well, it's a culture of convenience, and it gets back to your point that technology is a double-edged sword, right? Technology has, in the Industrial Revolution raised more people out of poverty than ever before. And it's created a straitjacket of convenience that essentially has made... Even though we've raised ourselves out of poverty, people are way more susceptible to sickness, they're way less able to actually connect with the Earth and navigate the Earth and the land. They're way too reliant on these abstract things. I go back to your point about this guy who did Ayahuasca and thought about Bitcoin, right? These abstract financial things that aren't actually rooted in truth, which is our relationship to the land, our relationship to community, our relationship to the Earth. And it feels like once you start to strip away all that convenience, you're actually left with something that's much more honest, and I think that's difficult for people to face.

0:59:00.3 MP: You're right, Paul, I think that we all understand the benefits of technology. We all have iPhones, we all have notebooks. We also have to understand the price that we pay, and try to minimize that, because most people don't, they're just like this all the time. Right? And then we wonder why we're so stressed out. And I think that hallucinogens are part of the answer. I think that microdosing is part of the answer, but there's no panacea. It's how do you balance this connection to the natural world with using technology? You know, I have a car. I don't want to be a hunter-gatherer. One of my best friends is a hunter-gatherer. He used to be a hunter-gather, and I see what's better, and I see what's worse. So that, you know, he said, "before contact, we were always searching for food, we never went hungry, we're great hunters." He says, "now there's all the food we can eat, we get fat." It's part of the trade off.

0:59:54.0 PA: Everything in moderation. And, and... Yeah, everything in moderation. So I'm mindful of time, I have one last question for you. And we sort of talked a little bit about it, just weaving it throughout this conversation, but just sort of looking forward now, and because this podcast is about psychedelics, and because of how familiar you are with the Psychedelic Renaissance, and a lot of the things that are going on. In an ideal world, you know, as psychedelics grow in popularity, as people become more aware of the need to take care of the Earth, to take care of the Amazon as a result of using psychedelics, I think that's a that's a hope that I have as well. What's sort of a best case scenario, if you will, of how this third wave of psychedelics plays out in the next 5 to 10 to 15 years, from your perspective as an ethnobotanist, as a conservationist, and as someone who, you know, was a mentee of one of the greatest teachers in this space?

1:01:00.0 MP: Well you're Mr. Third wave I should be asking you, but from my perspective, the best case scenario is, first of all, the psychedelics will be available to everyone in a controlled, standardized setting, that the issue of money is resolved in favor of people who should be getting a fair share of any benefits that come from this, the financial not just the therapeutic, that there's more appreciation for the natural world, and it's not about how much Ayahuasca do I have to take before I can make money on Bitcoin, and that they're not over celebrated and oversold as the cure for anything. You know, Michael Pollan's book, Changing Your Mind is replete with stories of people who had emotional problems and went to the Amazon and kind of fell apart. And all of us who've been around the block, know stories about people who thought that this was the answer to everything, and ended up worse off. My buddy, Tim Ferriss talks about this as well. So it's very important that the things be looked at in perspective, that psychedelics are not the answer to everything, that they are a valuable and potentially even more valuable, a tool in our tool chest.

1:02:06.4 MP: The other thing is that we are able to create enough shamans so that you also have the ability to take this in a relatively traditional setting. And it's not just all white Jewish guys and lab coats like me, giving you a couple of pills and thinking we've got it all figured out. I gave the commencement address at Tulane Medical School a number of years ago, and I said that I talked to one of the greatest shamans in Northwest Amazon, one of the premier Ayahuasqueros, and I said, "how long have you been studying healing with Ayahuasca?" And he said, "Well, you know, in your age I'm 85." He said, "I started drinking the remedio 80 years ago, I'm still learning." So the idea that, you know, that's a medical school...

1:02:56.3 PA: With medical school, we just... You go for 4 years and then...

1:03:01.0 MP: Yeah, it just shows you the profound humility and respect that I think allows this man to do things... He's gone now... To have done things that our own physicians will probably never be able to do.

1:03:14.7 PA: And just as a follow-up question to that, what is going on right now in the Amazon in terms of the... In terms of shamans and in terms of like it is, is that a... Obviously it's not a job, it's not a profession, is that a way of life that's becoming more popular with those in the Amazon, as Ayahuasca grows in popularity or just kind of what's the sort of... Yeah, what's going on there? With training and all that.

1:03:41.6 MP: I've been going to the Amazon over 30 years ago, and I would find the shaman and ask him or her to teach me, they would be stunned, they would be flattered. No white man had ever done this and very few of their their grandchildren, sons or daughters or granddaughters were interested in this. So that was kind of a revelation. However, and they were looking at the other side of the coin where you know, you say, "I wanna learn from you, I wanna take Ayahuasca, I wanna take hallucinogens." They roll their eyes, There's a great headline in the Onion, that said, "Ayahuasca shaman dreads another weekend of tech CEO seeking spiritual oneness." Okay. That kind of sums it up, but the good news is it's made shamanism a respected tradition again, and it's like I tell some of my indigenous colleagues and then remember that traditionally very few tribes took Ayahuasca, this was not ubiquitous.

1:04:33.8 MP: In the Amazon here, between 300 and 400 different tribes, I covered this in my last book, The Amazon What Everybody Needs To Know, came out last year, so that the idea that all shamans use the same plant, all shamans take Ayahuasca, it's simply not true. In fact, you should have Glenn Shepard on the program next, the great ethnobotanist, he compares two tribes living next to each other and talks about how their whole ethno-medical system is radically different. So that the idea that being a shaman is a respected profession is a very positive thing, the downside of that is you have a lot of guys saying they're shamans, that they're not. I mean the good news here is when you go to the doctor, she or he has an MD and a degree on the wall, who's a shaman? There's lots of Rent-A-Shamans in Iquitos, and that's where a lot of these problems are coming up.

1:05:23.9 MP: So we really did need a certification program, and then that gets in the issue of how western do we wanna be and who decides who's a shaman? We've done this actually in the Northeast Amazon, and we tell our indigenous guys, "maybe you wanna set up a system based on what you used to do in the past before the missionary could, and you decide who is and isn't a shaman." So the ball is in their court to make the decision, but that's very important 'cause it can't be all about the money, because it's a sacred tradition where money never changed hands in the first place.

1:05:54.4 PA: Right, right, and this is of course an issue, not only in the Amazon, but this is an issue in the United States, in North America and Europe. We see therapists or psychiatrists as the shamans of western culture so to say, and that's a big question, even in our credentialed, professional context, who's qualified to be a therapist, who's qualified to be a guide, who's qualified to guide people through some of these really deep, dark moments of their lives? And there's, like you said, there's no simple answer, every complicated answer has a simple... Where every complicated question... There's a simple answer, but it's wrong, and that's often the case when it comes to a lot of this work with psychedelics, it's like... And this is even something that with Third Wave, we're trying to help with, we've rolled out a directory of vetted clinics, retreats, therapists, coaches that go through a process where we help to vet them, but we don't know everything. We can't vet and verify everything, so I think this challenge, so to say, what you're speaking to will be central to the success of how this grows and develops as a larger movement.

1:07:02.1 MP: Well, when you know the few students, Paul that get through the guard dogs that surround me, that ask about the future and then what the jobs are gonna be? My first answer is always, "20 years from now, tattoo removal will be very big." Okay? [chuckle] Number two, if you're interesting in healing and you're interested in hallucinogens, hey, there you go, that we need more people who have expertise in this, guides is gonna be very big, but it shouldn't just be all about guides, you need psychiatrists, you need shamans, you need all of these things, but here's an ironic aspect to this. I get asked all the time. What's the difference between taking Ayahuasca in a maloca roundhouse with a shaman and taking Ayahuasca in a clinical setting with a physician? And the honest answer is, I don't know. I've never done it in a clinical setting, so I know more about this than many and I don't know any guides, right?

1:07:56.7 MP: So that clearly the need is there and will only grow, and now is a good time to find people who are good of heart, that really have a call to heal, that they should be thinking about this as a career path. And let's face it, not everybody can get into medical school and not everybody should go to medical school, for a variety of reasons, but massage therapy, aromatherapy, being a psychedelic guide, all of these things need to be part of the offering of people who feel a call to help other human beings, because those needs are not being met. And given the moneys that are pouring in, given the soaring demand for this stuff, I can't see anything other than a bright future for people who wanna do this in a professional way, be able to earn a living, and as importantly, if not more importantly, earn a decent living in the process.

1:08:48.0 PA: And it goes back to your point about Schultes versus Leary. Schultes, when he was doing this work, the '30s, the '40s, the '50s, he had that long-term view in mind, and I think anyone who's coming into the space, this is something I often vet for and test for is, what are your intentions, and why are you here? Usually, if it's just as, let's say superficial as money, cut them out because that won't stand the test of a lot of the challenges that one might face when doing this work, but if you're really in it because you really wanna help both yourself, but more importantly others be guided through, then what I find is those people are, "this is the next 10 to 20 to 30 years of my life, and it's something I really wanna commit time and energy to," and I think that is a really good signal of integrity and a heart being in the right place for this type of work.

1:09:41.7 MP: Well, that's where I like to feel like I'm honoring Schultes' legacy, because he was never about, you know, how can I just make a bazillion dollars with this stuff? He was all about understanding it, protecting it, publishing it in a respectful, way rather than, "okay, how and where can I cash in the chips ASAP?" And I run a not-for-profit, when I hear all of these capitalizations of half a billion, $3 billion for Psilocybin, it's... That's not why I'm in this business.

1:10:17.5 PA: It's absurd. [chuckle] That's absurd.

1:10:17.6 MP: And I'm glad some are doing it, it's not me. I'm not interested, I'm more interested in the fact that the Mazatec shamans are complaining to me that some species or varieties of mushrooms are disappearing because of climate change, that to me is something that I'd be much more interested in tackling rather than being out there proselytizing that everybody should be drinking Ayahuasca. I'm the head of ACT, we're the Amazon Conservation Team, we're not the Ayahuasca Conservation Team.

1:10:41.6 PA: I love that. Well, Mark, thank you for, first of all, joining us for this episode today, thank you, more importantly, for the work you've done in the last 40 years for the conservation of the Amazon, for the work that you've done with Ayahuasca, but more generally plant medicines, for the book that you wrote, Tales of a Shaman's Apprentice, which I highly recommend everyone pick up. It's a phenomenal read. I remember I read it earlier this year, I woke up at 6:00 AM and would just, for an hour or two hours, for a week or two straight was just going through it 'cause it's such a good read, and thank you for continuing the legacy of your mentor, Richard Evans Schultes, I think the work that he pioneered is still central to the lessons that we're learning in this third wave of psychedelics, and the fact that you are the individual who... You are one of many, but I think in particular, you're holding a lot of that, it feels very good and solid, and so I just appreciate everything that you have done, that you are doing and that you will do for the Amazon and also for these important plant medicines.

1:11:47.4 MP: Thank you, Paul.

1:11:48.0 PA: Thanks so much for watching. If you wanna stay up-to-date on the Third Wave Of Psychedelics, subscribe to this channel and visit the thirdwave.co, where you'll find plenty of free resources on intentional and responsible psychedelic use.