Psychedelics & Palliative Care: Finding Fulfillment in Life & Death

LISTEN ON:

Episode 178

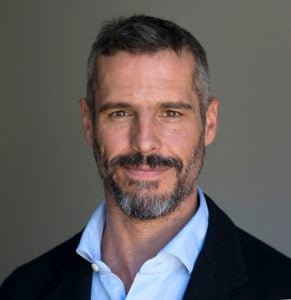

BJ Miller, M.D.

Paul F. Austin is joined by BJ Miller, M.D., co-founder of Mettle Health, for a discussion on psychedelics and living and dying well.

BJ Miller, M.D. is an established thought leader in the area of serious illness, end-of-life issues, and dying. He has been a physician for 19 years and has counseled over 1,000 patients and family members. This vast experience has led him to understand what people really need when dealing with difficult health situations.

BJ has given over 100 talks, both nationally and internationally, on the themes of serious illness and dying, He has given over 100 media interviews, including podcasts, radio, and print. His TED Talk, What Really Matters at the End of Life has been viewed over 11 million times. He is co-author of the book, A Beginner’s Guide to the End: Practical Advice for Living Life and Facing Death, published in 2019.

Podcast Highlights

- Powerful insights and perspectives from BJ’s work in palliative and end-of-life care.

- From taboo to opportunity: examining attitudes towards death across cultures and history.

- How BJ became involved in the intersection of psychedelics and end-of-life.

- Looking at the data on psychedelic therapy for patients with end-of-life anxiety.

- “Anesthetics vs. Aesthetics”: BJ’s insights into a helpful set and setting for dying well.

- Embracing regret and fear at the end of life.

- The power of love—during life and at the time of death.

- Mettle Health, BJ’s service for patients and caregivers.

Show Links

This podcast is brought to you by Third Wave’s Mushroom Grow Kit. The biggest problem for anyone starting to explore the magical world of mushrooms is consistent access from reputable sources. That’s why we’ve been working on a simple, elegant (and legal!) solution for the past several months. Third Wave Mushroom Grow Kit and Course has the tools you need to grow mushrooms along with an in-depth guide to finding spores.

This episode is brought to you by Apollo Neuro, the first scientifically validated wearable that actively improves your body’s resilience to stress. Apollo engages with your sense of touch to deliver soothing vibrations that signal safety to the brain. Clinically proven to improve heart rate variability, it can actually enhance the outcomes of your other efforts like deep breathing, yoga, meditation, and plant medicine. Apollo was developed by a friend of Third Wave, Dr. David Rabin M.D Ph.D., a neuroscientist and board-certified psychiatrist who has been studying the impact of chronic stress in humans for nearly 15 years. Third Wave listeners get 15% off—just use this link.

Looking for an aligned retreat, clinic, therapist or coach? Our directory features trusted and vetted providers from around the world. Find psychedelic support or apply to join Third Wave’s Directory today.

Podcast Transcript

0:00:00.0 Paul Austin: Welcome back to The Psychedelic podcast by Third Wave. Today, I'm speaking with Dr. BJ Miller.

[music]

0:00:08.6 BJ Miller: So the research around Psilocybin on folks who were dealing with end-of-life anxieties, whether they were on their death bed or upstream of it, was trying to see its effect on that knot, that gripped them and got them stuck. And one psychedelic experience with psilocybin, guided, with some attention to set and setting, careful observation and integration, one experience loosened that not for just about everybody involved.

[music]

0:00:46.0 PA: Welcome to The Psychedelic Podcast by Third Wave. Audio mycelium connecting you to the luminaries and thought leaders of the psychedelic renaissance. We bring you illuminating conversations with scientists, therapists, entrepreneurs, coaches, doctors and shamanic practitioners, exploring how we can best use psychedelic medicine to accelerate personal healing, peak performance and collective transformation.

[music]

0:01:19.5 PA: Hey listeners. I'm so excited to have Dr. BJ Miller on the podcast today. BJ is a physician, author and speaker, and has been practicing Hospice and Palliative Medicine for many years. And is best known for his 2015 TED Talk, What Really Matters at the end-of-life. BJ has been a thought leader in the space of death and palliative care and hospice for many years now, and in particular, he was influenced in this process by his own accident that happened when he was in college, which we'll talk about on the podcast. And so we go into sort of a range of topics, we talk a lot about death, we talk a lot about regrets at the end-of-life, we talk a lot about what it means to actually live a very meaningful and fulfilling life, and then we go into the role that psychedelics can play in helping to manage and clear fear as it relates to transitions in the end-of-life. BJ is very humble, very kind, and it really was an honor to be able to speak with him for today's podcast conversation. However, before we dive into today's episode, a word from our sponsors.

0:02:44.4 PA: After hundreds of conversations with our listeners, we found that the single biggest problem when most people begin to explore the world of psychedelics is sourcing the medicine. So we've developed a creative solution. Third Wave's Mushroom Grow Kit and video course. Just go to thethirdwave.co/mushroom-grow-kit and use the code 3W podcast to get a $75 discount. I've experimented with a lot of different grow kits in the past and this one is seriously next level. We've partnered with super-nerd mycologists to make this the simplest, easiest grow kit possible. It's small enough to fit in a drawer and most people get their first harvest in four to six weeks. You get everything you need right out of the box, pre-sterilized, and ready to use. Except for spores, which we can't sell for legal reasons. And speaking of legal issues, growing your own mushrooms for "scientific purposes" is 100% legal in 47 states. You can have your private supply of medicine without the risk.

0:03:25.1 PA: Our course also comes with a step-by-step high-quality video program showing you exactly what to do when you receive that mushroom grow kit. No blurry photos or vague language. You'll see exactly what to do each step of the way. Yields range from 28-108 grams, so this more than pays for itself in one harvest. Plus, you can get up to four harvests per kit. This is the simplest way to get a reliable supply of your own psilocybin mushrooms. Again, just go to thethirdwave.co/mushroom-grow-kit and use the code 3W podcast to save $75. The number three, the letter W podcast to save $75.

0:04:28.2 PA: Hey, listeners. Today's podcast is brought to you by the Apollo wearable. I first started wearing the Apollo in the midst of the COVID quarantine over two years ago. It helped my body to regulate itself, to calm down, to stay more focused, and to meditate in the morning. And I use it to really regulate my nervous system in a time of incredible stress, and I've continued to use it on a day-to-day basis. It is indispensable in my daily routine. Here's the thing. The Apollo is a wearable that improves your body's resilience to stress by helping you to sleep better, stay calm, and stay more focused. Developed by neuroscientists and physicians, the Apollo wearable delivers gentle soothing vibrations that condition your nervous system to recover and rebalance after stress. I tell folks that it's like a microdose on your wrist that helps you to feel more present and connected, especially when in the midst of a psychedelic experience. It's a phenomenal compliment to any psychedelic experience.

In fact, Apollo is currently running an IRB-approved clinical trial in conjunction with MAPS to understand the long-term efficacy of the Apollo wearable with PTSD patients who have undergone MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. The Apollo wearable is the only technology with an issued patent to reduce unpleasant and undesirable experiences associated with medicine-assisted therapy, including psychedelics and traditional medicine. And you can save $50 on the Apollo wearable by visiting apolloneuro.com/thirdwave. That's apolloneuro.com/thirdwave.

Alright. That's it for now. Let's go ahead and dive into this episode. I hope you enjoy my conversation with Dr. BJ Miller.

0:06:20.1 PA: Hey listeners, welcome back to The Psychedelic podcast. Today we have Dr. BJ Miller who will be joining us for an episode on death dying palliative care and the role that psychedelics can play in that process. Dr. Miller it's really a pleasure and an honor to have you here.

0:06:35.8 BM: Thank you Paul. It's nice to be here and please call me BJ.

0:06:40.5 PA: I'll call you BJ, I like that. Alright, so as I mentioned before, we started the podcast, we've been recording episodes for the last six years. And we haven't done one on death and dying and as many of our listeners are aware of, there's a lot of exciting research at the intersection of psilocybin in particular for end-of-life anxiety. And as context for this, the ancient Greeks used to have a phrase that was basically, to die before you die means you won't die when you die. And this was part of... This was inscripted in the temples that they used to have the Eleusinian Mysteries in. And so I'm really excited to dive in today and talk about how can psychedelics help us prepare for death? Why is it that our culture is so afraid of death? How do we treat death? But before we get into those topics, the first place that I often like to start is your story. And to be one of the most prominent, if not the most prominent sort of thought leader on death and dying in the landscape, I'm just curious, what brought you to this? Why focus on death and dying? And why has it become really the center point of not only your professional career, but also I sense something that's deeply personally meaningful for you as well?

0:08:07.7 BM: Yeah, Paul, yeah thank you buddy. It's interesting the death and dying for me, it wasn't the initial hit for me that pulled me into medicine and into palliative medicine. But it has evolved that way, but I still don't even think of it, I still think of my... I'm interested in death and dying because it happens, because I'm trying to get right with reality. And as long as a reality seems to include death and dying, that's my interest. I'm interested in loving life as fully as I possibly can and therefore including as much as I can. And therefore I'm interested in death and dying. So I think that's an important qualifier. And for my own arc, I got injured in college, electrical burns pretty bad and came close to death myself. But at the time, it wasn't... That was a profound experience for me in all sorts of ways. But the early years as I was recovering from that experience, my mind went to issues around disability and how we suffer in all sorts of unnecessary ways, we treat disability, we treat death.

0:09:51.9 BM: We treat disability through an early thinking with, why do we isolate people who no longer whose body doesn't quite fit the normal silhouette or whatever it is? Why do we alienate ourselves from illness and disability and eventually death when these things just happen. So as a disabled person, you not only deal with the fall out of those changes in your own life, but you also have this feeling that you enter this... You to leave the world of the able-bodied and the independent people. And you've gotta go over here to this consolation prize, the second place world of dependency... Even all the language, disabled... Who gets to be the standard person against which we all measure ourselves? Who is this guy? And so when forced to reckon with a different body in a different life than I had anticipated or had known, I became really aware, and I had been aware of this thanks to my mother who had polio. I've been around disability my whole life. So this wasn't new stuff. But now it became very personal . . .

0:11:11.5 BM: So I was just, anyways, I was very interested in looking at how we, why we're so cruel to ourselves and to each other. Why we hold ourselves against standards that are impossible. Why do we end up hurting ourselves and each other more than we have to? So that was my way into medicine, so I went into healthcare, to medicine to kinda work in that zone. If my doctor had walked into the room looking like I'd look, I think it would have been a meaningful difference to me at that time. I was trying to find myself. So anyway, that was the impulse. I went into healthcare, and it was really late that I stumbled on to palliative care. I had heard of it, but I didn't... And I hadn't given it much thought. I thought I was gonna do rehab medicine, working with other people who had just gone through some sort of traumatic illness or experience. So anyway, long story short is, I did a rotation, an elective rotation in palliative care at the Medical College of Wisconsin where I was doing my internship.

0:12:16.2 BM: And I fell in love with the field immediately because, palliative care is simply, for your listeners, you know it's often conflated with end-of-life care, hospice, etcetera. But really important to understand that palliative care is a much larger umbrella. It's not just about dying, it's really, the focus of palliative care is helping people not suffer any more than they need to, and helping people realize themselves in the world and realize the joy in the world. So it's about mitigating suffering and maximizing quality of life.

0:12:53.2 BM: And that big umbrella, sweeps into its fold, end-of-life care in hospice, because these are things that people by necessity have to eventually deal with. So, that was my way into death and dying, end-of-lifey and stuff, was that was the context that pulled me towards the end-of-life. Which when I started working at UCSF as a junior faculty person, and I was continuing to weigh... Continuing to ponder my own experience, I came to see myself of having little deaths, that there was a death of my identity when I became injured, there was death of my limbs. And then you start cracking open around that and you start seeing death all over the place, literal and metaphorical.

0:13:41.4 BM: And then I started to realize how much it did for me to go through that process, much like your intro around the ancient Greeks. I experienced that sensation, that feeling that, "Wow, I'm so glad to have died before I die." Because it really sets you up to live very fully, very richly, and to not kick anything out of your experience. And so that was happening for me personally, and meanwhile I'm meeting a lot of patients who are at the end-of-life, because palliative care finds itself in the mix at the end-of-life for many people. So it was all kind of coming together, but it was... And then I went to work at a place called Zen Hospice Project for several years, and that's where I really started focusing in on this particular issue, question, dying, how we die etcetera.

0:14:33.8 BM: But again, only because there was this concentrated, very precious zone where time was really short, where these ideas, these issues, these feelings were no longer abstract, death was really in the room. And that reality, then sculpted, has sculpted the rest of my career, and so I keep finding myself talking about death and dying, but what I really think I'm talking about is life and living.

0:15:01.9 PA: And it speaks to the sort of dualistic nature of existence that when we're able to... Whether it's through psychedelics or whether it's through a near-death experience, or whether it's even through things like breath work, vision quests, there are so many modalities to... Fasting. That experience then... That experience of death, so to say, creates this voluptuous awakening of, "Oh, there's so much beauty to be grateful for in life. And there's so much richness and connection and love and understanding and... "

0:15:44.3 BM: I love that word, Paul, voluptuous. Yeah, that's right.

0:15:48.4 PA: 'Cause they're from... Culturally, it feels like death is very much a taboo, and that was sort of the next question that I wanted to open up for you. I read a book many years ago about taboos, and I forget the exact name of the book title, but it was something about how we as a Western society fear death, and that fear of death is... Dictates so much of our neuroticism and so much of our suffering even. And so I'd love to hear you talk a little bit about, why is it that death, in particular in Western cultures, is such a taboo and sort of off-limits? Why is it that we stick old people in nursing homes and refuse to visit them? Why is it that hospitals are so industrial and not really comfortable places to die? Just... Yeah, bring us into that a little bit.

0:16:43.0 BM: Yeah, that's a big question. I mean I think there are a lot of answers to it, a lot of layers to it. One is, I like to remind myself and others... Because there's a critique, the rest of the things I'm about to say about it, there's a criticism in here, and... But like many or most, or all things, these impulses come from somewhere, not just... So I think it's actually very useful to just work with what we have, including this fear, including this repulsion and see what's in there. So one is to say, from medical training, you learn very quickly that we're wired, we have a reflexive, it has nothing to do with our thoughts, a reflexive, we will run, we will fight or run away from anything that's threatening our existence.

0:17:37.8 PA: Fight or flight.

0:17:38.3 BM: And that's at the... Yeah, exactly. That's your wiring, it's not your choice. So let's start there. That's okay, fair enough. So we're not just all in denial, in other words, we have this drive to avoid dying. Okay, so fair enough. The problem is... Or not a problem of... Well, maybe a problem, maybe an opportunity is, that's in the acute moment where epidemiologists, natural historians, biologists will tell you, "Yeah, it's great if you have a Saber-toothed tiger, walks in your room, you need that kind of energy mobilized real fast." Truth is, most of us don't hang around with Saber-toothed tigers anymore. And so it has gotten really kind of... All these boundaries between acute and chronic, "Real fears or actual physiologic fears in a moment versus sort of the fears of our mind and our imagination." It's all kind of vaguely differentiated. So the fact is... One of riddles of being a human being, and it does feel like a riddle to me, Paul.

0:18:58.3 BM: And you look at the roots of a lot of religious, sort of whole religions, look at the origins of Judeo-Christianity, we ate from the Tree of Knowledge right. We took the apple, not from the Tree of Life, we ate from the Tree of Knowledge. So we humans were cursed like a punishment, we had to be, we had to have the burden of knowing things. Maybe chief amongst them is we got to know that we die in advance of our death. And that can feel like a curse.

0:19:37.1 BM: And so now we're bringing religion into it. We got a whole religion that calls this a punishment for original sin, right? So that, "Dang it, I gotta know that I die before I die." Religion can be helpful in some ways and hurtful in some ways, of course, right? So I don't see it as a punishment anymore, just it is what it is. So I gotta know I die, well, how can I work with that? Where is the opportunity in that? If that's just the fact of being a human being or being a conscious critter, well, where's the opportunity in there? I think we humans get really creative when we learn to want the things we need, whether... I think about this with food. You could say, "Oh, poor humans, we gotta eat stuff to survive, we gotta go find food." Or, "Poor humans, we need shelter to deal with the weather," or clothing, whatever. But humans turn those into opportunities. Like now we get to... Like architecture, fashion, cuisine, all these things. We've turned... We've made these needs our own by leaning into them and working with them and playing with them. It's so beautiful.

0:20:51.3 BM: And so if we need to die, well, where is the version... What can we do there? How can we play with that, how can we work with that? And one of the things that I and many, many, many people experience is, well, it's not that I want to die, but because I have to, you can let that, like you say, bring you in this voluptuous experience with life because it is so precious, because it doesn't last. That's not a problem, really. That's what lights it on fire, that's what gives it this sort of this power. So, I'm getting a little far afield from your question, I'm kind of heading towards opportunity but to back up, yeah.

0:21:30.5 PA: No, this is good. This is good.

0:21:34.0 PA: Okay. Well, so to back up a little bit, back to why we... So, we've named biology, we've named religion. There's two big reasons why death is this, this problem. It's a problem. So, sticking with the problem for a moment. And I think it's very helpful to see our flight from death as a piece of the flight from nature. For whatever reason, especially in the West, we decided that it was man versus nature, as though man, human is not nature. And look at the fallout of that one. [chuckle] That's all over the place. That, and we are living in a, I hope in a sense, a reckoning of the short-sidedness of that that false separation. We have pulled ourselves out of nature to conquer it, and all this stuff. So that, I think is a big answer to your question of how the hell did we get here? So we have been at war with nature in all sorts of ways, death being one of them. And because we've been in some ways, especially in the 20th century, pretty successful with that death... But again, you've already brought in ancient Greeks, this is not just a modern phenomenon. But we have just gotten more and more... You can avoid big truths for a long time.

0:23:06.4 BM: You can live in a... I live here in a apartment, brick apartment building where I keep all sorts of nature is kept at bay here. And in some ways to my great convenience and luxury, but ultimately there's a cost for it. So, this attitude towards nature, it spilled into our attitude towards death and made it a problem. Healthcare, medical world, this invented model that is profoundly powerful and saved my life, that model took it upon itself to demonize or pathologize all sorts of normal events. Who's never gotten sick? In the medical model, that's pathology. There's something wrong with you. Okay, again, as a convention, fine, let's call it a problem, fine, and we differentiate normal from pathological. And it's a convention and it has its utility, but it also has its fallout. So the medical model has driven us farther and farther away from the truth of nature. And the medical model is, we got a problem, and call it pathology and go to war with it. If we just think hard enough and study hard enough, we'll beat it. So that has certainly played into this spastic distancing from death.

0:24:34.6 BM: And then on top of all that, so we've got biology, religion, we've got modern medicine and the medical model and our inventions, including this sort of man versus nature, our own, and you could just take that back to Descartes perhaps, as dualism that you mention, this duality. That we have falsely separated ourselves from reality. That was a huge pieces of puzzle. And I think lastly probably is on the level of cultural and social, which is beautiful, wonderful vague social science of sorts. How culture moves, how society moves, how our thinkings and our metaphors shift. A lot of our experience flows from those constructs. And so, somewhere along the way, we've kind of inherited superstitions, like if I say I die, then I'm gonna die. If I don't say it, it won't happen, and stuff like that. So, put all that together, and probably some other things I'm not thinking of right now, and that gives us, I think... That tells you why we are where we are.

0:25:55.2 PA: I'm taking lots of notes, so you'll probably... At times, I write things down and there's a few... One phrase I wrote down is, "Death is not a bug to be fixed." And I think there's a propensity in particularly Silicon Valley, however we wanna currently define Silicon Valley post-COVID, kinda these technocrats of, how can I live forever? And of course, this has been going on for thousands of years. We've been looking for the fountain of youth and longevity and how we live forever. And yet the truth of it is progress, positive change, the evolution of consciousness only happens through death because as generations die, the sons and the grandsons and the great-grandsons can take the mantle and shift and change, right? There's a lot of shadow, I think, to this avoidance of death.

0:26:54.9 PA: And then on the man versus nature part, we had Jeremy Narby on the podcast about a year ago or so. Jeremy wrote a book called The Cosmic Serpent where he talks about how with the Shipibo when they work with Ayahuasca, baked into their language is a clear understanding of how connected they are to the forest and to the world around them, and how in English, in our very language, it's baked in that sense of separation. So it's almost like from birth, we are born into a cultural system that teaches us on every level to fear nature, to fear death, to fear the unknown, I would say to fear the feminine and the dark, and so what that is, which then becomes amplified through the current medical model and becomes amplified through our attachment to materialism and all these other things.

0:27:52.2 BM: Yeah, and by the way, on that note, sorry if I'm interrupting, Paul...

0:27:54.4 PA: No no please.

0:28:00.3 BM: But that we are, this is part of the sort of irony or whatever the right word is, that we are victims of our success. I mean, the technological revolution is profound. It is amazing. The problem is, of course, we invent things that are so powerful that they will use us, versus we. If we could just keep the order right. We use the technology, it doesn't use us, you know what I mean. Let's get clear about that. So anyway, we are victims of our success. It is absolutely seductive nowadays to think that you could make death sort of optional. It feels almost within reach thanks to our successes in these various models playing themselves out.

0:28:36.5 BM: Language is a huge one. We do this all the time in medicine. We call death a failure and blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. So anyway, just to highlight what you're saying there. But can I also mention one other thing that you said when you were talking about fear. I also... I think it's important that we don't accidentally ostracize may be anything, including fear. Fear is natural. Fear happens. I don't believe people who say that they're never afraid. And the distinction here is, I think what you're pointing to is we have come to hate fear versus welcome it and work with it as just like anything else that's part of our raw material in this life, and this raw emotional material in this life. So I don't think there's anything wrong with fear. Fear makes a lot of sense to me. Hating fear and trying to stamp it out of your life, that's where I think the trouble comes.

0:29:31.0 PA: And so there's discernment there. From a physiological perspective, right, there's a reason we have an amygdala, there's a reason that we have the fight or flight response. It's helped us to survive and thrive for thousands and thousands of years, and yet, as you mentioned before, the saber-tooth tiger example, there is this sort of constant neurotic fear that seems to envelop everything, that's driven by scarcity, that's driven by lack of worthiness, that's driven by I think a lack of connection. And this is, I think, a good transition point for psychedelics to some degree because psychedelics are one of the tools then that they can help to dampen that fear response, they can help to dissolve the construct of the individual ego, to see beyond sort of our narrow viewpoint. And I'd love, kind of as we open this up a little bit more, just to hear like, when did psychedelics come into your awareness? Was it through the research? Was it through other means? At what point did you realize psychedelics are phenomenal tools for that palliative care for suffering, for death and dying, for life, and exploring life?

0:30:39.5 BM: Well, I guess I have long been interested in altered states. So, sometimes in a constructive way, sometimes in a destructive way. Earlier in life, I loved my booze, I loved my weed. I still do, frankly, but let's be careful with this stuff.

0:31:06.5 PA: In moderation, right? In moderation.

0:31:07.6 BM: In moderation, including moderation. So I think for me, my own arc has been, just an interest in altered states. And if I got past the taboos of it, the mores of it, I think my body knew something, it was also doing something interesting, whatever else, whatever shortsightedness I was demonstrating, I think I was also... There's something, the kernel of something good in there was really about triangulating, sort of shifting my perspective, because it helps me understand that my perspective is not the same thing as the truth. It is how I experience truth, but my perspective is changeable, it is malleable. And so by triangulating with these altered states or moments in some altered state, help me triangulate my own perspective. And therefore, help me play with it and help me not confuse it with the truth. So that's the best part of what I've ever been up to with pursuing any altered conscious state. But psychedelics specifically, it was on the list of things I would have played with back in the day in the form of mushrooms or LSD, but not a ton. Not a lot. There was a summer I had it when I was...

0:32:40.9 BM: I guess this is the summer before my injuries, actually. Somewhere between freshman and sophomore year of college. I was at Chinese Language summer school in Indiana, and a buddy of mine, Mario, he and I...

0:32:51.6 PA: Of all places.

0:32:53.8 BM: Yeah. [chuckle] And he and I spent a lot of time playing with LSD, and mushrooms it was wonderful experience. But that was pretty darn recreational. We would take this stuff and go watch... We watched Gremlins 2 in the movie theatre at the mall, like 30 times that summer, [laughter] literally.

0:33:13.4 PA: Was David Bowie in that one as well? I know he was in the original Gremlins.

0:33:17.0 BM: Was he? Oh, I love David Bowie.

0:33:18.8 PA: I think so, hard to keep track. David Bowie is phenomenal, talk about psychedelic. [chuckle]

0:33:23.3 BM: Yeah, what a man. So anyway, so I played with it in this way, but I didn't really know what I was doing. It wasn't conscious. But I'd also, again, it was not destructive either, not intended to be. So, back to your question, it's really... Like a lot of us, it's sort of the resurgence that's in my role as a physician, working with people, trying to help them get right with themselves before they die, that psychedelics kept coming back into the mix one way or another, the conversation increasingly through the work of folks like Tony Bossis and others. Bill Richards, an even wonderful man, holy cow. So, just like a lot of us, as the doors opened up again to return to research, that portal opened up and I started to see it in a much bigger context, much more historical, potent, ancient context that, like so many of us I got more and more interested in the stuff.

0:34:25.4 PA: In that initial research, I think it was Michael Pollan's article, The Trip Treatment, which he published in the New Yorker in 2015, where he had interviewed Tony, he had interviewed a number of cancer survivors. He had sort of asked them questions about what they had experienced. And one thing I picked out as well, which goes back to your point about palliative care, I don't... Although it was framed as end-of-life, there were more than a few people in these research trials who went on to live for many, many years after that, that psilocybin experience as well. Now, and if you need to pun on this question, you're more than welcome to, since I know this isn't necessarily your specialty. But just for our listeners, can you tell us a little bit about the research around psilocybin for end-of-life anxiety in terms of why it is an effective tool to help with suffering in palliative care? And maybe within that... I was watching your phenomenal TED Talk, which I would recommend that all of the listeners go check out after this. It's from, I believe 2016 or 2015.

0:35:37.7 PA: And you talk about the role of design in death and aesthetic, and so I'd love to also hear your thoughts on so much we talk about set and setting with psychedelics. And I often think about the Aldous Huxley story where Aldous injected himself with 100 micrograms of LSD in his death bed to go into the white light. So I'd love just to hear a little bit about the research and then your thoughts on designing spaces and maybe the role that psychedelics can play in palliative care and hospice care as we... As they become legal, as they become medicalized, as they become more available for people who are suffering with end of...

0:36:19.6 BM: Yeah. And thank you for the caveat, I am not a scholar on anything, really, including psychedelics. And actually it's funny you mentioned that article by Michael Pollan. It may be, if I had to pinpoint a moment where my eyes got sort of re-opened to this vast potential. Michael Pollan, I met him when I was at Zen Hospice Project, which was probably... And I think he came to interview me around that article, I think. I don't know if I made it into his article, but I think I owe him the... Yeah, I don't think I'm in... I don't think I said anything worth printing at the time. [chuckle] But I think I need to credit him coming to see us at Zen Hospice Project, because the question of course was, "Do you guys here, you're dealing with death all the time. Do you see a need or a place for psychedelics?" So it may have been that conversation with him which would have been around 2014, maybe 2013, 2014, something like that. So just to give him his due, that tuned me in again. But back to your question, I think... So my read on the literature, again, not as a scholar, not in great detail, but the gist is, and what I see all the time in my own practice was whether someone is dying in a week or in a decade, when they're given a diagnosis of an illness that will someday take their life, an advanced cancer, people can live for years with cancer.

0:37:58.0 BM: But wouldn't that abstract thing, Yeah, yeah, everyone dies, we all die, okay, fine. Yeah, you get hit by a bus today. Sure, fine. It's not even a useful... I wish it were useful of a refrain, because there's some real truth into that. But it's just such... It's just such white noise, we can't even really hear it. It's just too abstract. But when you get a diagnosis, and all of a sudden, you have a sense of the specificity of your finitude, it can really undo a person and back the sort of mind, excuse my language, a mind-fuckery of knowing we die before we die, that thought can cease to be compelling or useful. It can be a trap. You can just perseverate on it, and it can shut you down. And I see that not uncommonly, especially when I was at UCSF at the cancer center there. People who had these diagnosis, who now are introduced to the thing that was like a time bomb and then someday gonna take their life, and that sent them into this vigilante state, this grit state.

0:39:07.9 BM: And so the research around psilocybin on folks who were dealing with end-of-life anxieties, whether they were on their deathbed or upstream of it, was trying to see its effect on that not that gripped them and stuck... Got 'em stuck. And the... One psychedelic experience with psilocybin, guided, with some attention to set and setting, with careful observation and integration, one experience loosened that knot for just about everybody involved. And if there were any untoward side effects or folks who went the other way, I don't think there were. I don't think there... It was sort of zero bad stuff and lots of good stuff. And I don't wanna be cavalier here. I think you could hurt yourself with psychedelics. I think you could hurt yourself with a pencil. You could hurt yourself with just about anything. So I don't wanna be cavalier.

0:40:10.5 BM: But the data within this careful context, practically zero downside, and this huge upside of... I've been, as a physician, my... In my repertoire to deal with people who are knotted up around their own death and was sucking the life out of them before they died, they were in a bad, in a not helpful way, they were dying before they had to die 'cause they were so stuck. I could talk to them, I could try to normalize their experience, I could give 'em Valium to ease their nervous system, I could distract 'em with opiates. And that was about it. It's not the same thing as undoing that knot. But here in these research studies, consistently, folks who met this description were having these transformative experiences, and these experiences lasted beyond, whatever, however many hours the chemical was in their bloodstream. It lasted for months, maybe years, that it shifted their own relationship to death. It shifted their own sense of being gripped by fear around it. It helped them not... Maybe we can know we're... Everything is connected, we're all connected. But it's one thing to intellectualize that, but to feel that connection, to know it in your bones, to not need a word for it, you just know, to feel that connection is a powerful, beautiful thing.

0:41:44.5 BM: So what the... What people were reporting was that their fear of death went away. It's not like they stopped believing they were gonna die or anything, still knew that death was around the corner, but it lost its concrete potency. It was now much more porous. Like, Sure, I'm gonna die. This body is gonna die. My ego is gonna die and my sense of self's gonna die. But my body is part of this thing that's ever going, ever... Life and death are always swirling around each other completely entwined. And people absorbed that truth in this one experience, just amazing, just stunning. And again, the alternatives, it's not like we had something that worked nearly as well. We did not. Do not. So that data was just, you had to sit up and take notice. And so that's... Anyway, that's an answer to your question you might read on the research.

0:42:40.6 PA: And it's a beautiful summary. That experience of gnosis, right? Divine knowing, divine connection. It's interesting. Plato, after going through these Eleusinian Mysteries, was able to talk about substance duality, which through his own psychedelic experience, he realized that the soul and the body are actually separate forms, and that while the body dies, the soul is eternal. It's transcendent. It is connected to, let's say, the ground of all being, source, something greater and unknown and... I mean, this was... I was around the same age when I first started doing LSD and mushrooms as you were, and I remember the experience was so profound because I had been raised in a relatively religious home, being in West Michigan and Protestant and all that, and it never really clicked growing up. And yet, as soon as I had that first LSD experience, all of a sudden I was like, I get it. I get what these philosophers and what these mystics and what all these people are talking about. And so I think when we talk about untying that knot, there is so much anxiety around like, I am gonna die. And it's, as you said, it's... The anxiety of dying is actually creates a lot more suffering than the dying itself, to some degree.

0:44:14.5 BM: Exactly. Yeah.

0:44:15.8 PA: And so that capacity to untie the knot, then, allows for a much... Allows for an ease of suffering in people's last years, months, weeks and days, which is such a gift when it's so clear that the end is coming, the end of the physical form is coming.

0:44:41.8 BM: Mm-hmm. Right on.

0:44:46.6 PA: So kind of on the piggybacking of that, one thing that you had talked about in this Ted Talk, and we've sort of touched briefly on, but I would love to have a kind of a... Go a little bit more concretely into this is, you had this beautiful turn of phrase where you compared anesthetic to aesthetic. And that the anesthetic is... Obviously, it's something that knocks us out, whereas aesthetic is something that really brings us to life. So I'd love to hear sort of your thoughts, your perspectives, even the work that you've done and been a part of is when we're looking at those last months, those last weeks, those last days, what is a set and setting that really supports that death, that dying, that sort of process of easing suffering as people are going into that white light, if you will?

0:45:39.5 BM: Yeah. One way into this is... I came to even hear the word and think about aesthetics through the art world. But through conversation with a dear friend of mine, Justin Burke, who is a philosopher and who wrote his PhD on Hegel and on aesthetics, And he taught me so much. And so we would have these conversations about aesthetics. Me, I was just interested in art and I was interested in vaguely kind of like, What does a body do? Why am I interested in having a body. It's a source of pain, it's the thing that dies. And as I came very close to death, I became very clear, I loved having a body, a body, 'cause it feels things. Come to see my body as basically a sack of sensors, as a way to interface with the world, as a way... As a medium through which I experience life. And then this sort of extra layer... So that... So we would kinda intellectually talk about how cool aesthetics were or something like that, but it took a while for me to see this sort of therapeutic nature of it, which is essentially couple things.

0:47:08.1 BM: One is, if I think about where and what I missed when I was a patient in the hospital and what I love now, a couple things always come up for me. Riding a bicycle or a motorcycle and feeling this sort of gyroscope on two wheels and the ballet of moving through space and just not as transportation or as exercise, but just for its own sake to... As a sensation, or playing with the animals that I live with. I realized that those things just... That's all I wanted to do. I craved those things. And they were sort of simple things. And I... So all of a sudden, these things that were useless took on huge meaning, purpose, I don't know what purpose to rolling around with a dog on the floor is or riding a bike outside of transportation etcetera. It was its own purpose. It was a reason enough for living. It was a reason enough to be glad I had a body and a reason enough to be sad I would lose my body someday.

0:48:20.5 BM: So I started to feel this poignancy in sensation in the felt universe. And as I kind of... I kinda... I tried to hyper-charge my intellect as a younger person, thinking that was the way. But as I was having these realizations about aesthetics, I was realizing it didn't have anything to do with thought. You don't have to have a thought to have a feeling. And if you've been further honed by watching a lot of patients that I work with just be terrified of dementia, of cognitive decline, and I don't... I'm terrified of it. That doesn't sound great to me either. But I am increasingly aware that there's a world beyond our thoughts, that our thoughts is not... Aren't the... Isn't quite the same thing as a reality or thoughts about reality.

0:49:12.8 BM: So I got really interested that, A, here's this thing that's accessible. As long as you have a body, you have access to feeling something. It doesn't need a story of purpose, doesn't need a big narrative. It just feels in the moment, feels right or good or something. It's its own value. It's not a means to an end. It's not this thing we do to ourselves as sort of... We leverage our present moment for some possible future state, whether I withhold things from myself now so I can get more later, I can study really hard now and I'll become something down the road. All these things, we hijack ourselves a little bit, we hold ourselves a little bit hostage. Everything we see, everything in strategic terms is a means to an end. Well, where do means and ends collide? Where is the... Where are the means and the ends one and the same? That's the aesthetic world. Again, a feeling doesn't have to have a purpose, doesn't... There's no story required, no intellect required. And guess what? No time required.

0:50:16.4 BM: So as I started working with patients for whom time was this really precious and, Oh shit, I have... Now I'm aware I'm dying. I've got a couple months to live. How am I gonna weave together a life of purpose now? That may out of reach. And some people say, Well, that's it. Get me off the planet now. A lot of my time is coaching people to say, No, no, no, hang in there. Just isn't being enough. Isn't being enough? Not just being if I can be more productive or this utilitarian stuff. So all these things kinda came together, and I'm like, Holy shit, we're sitting on something really beautiful, profound, accessible, and requires no time, no thought. And as long as we have a body, great. And bodies, by the way, are the things I'm so sad to lose when death comes around. So just all these roads converged and kept pointing me to this aesthetic domain.

0:51:14.5 BM: And I'm so, so grateful for that. It has really helped me loosen my own knots around my own ideas of being of use in the world or whatever else or having a... Writing a story for my life that is really... Has a nice beginning, middle and end and all that stuff. That's great. Purpose is great. But my point here is I've learned it's not essential. There's stuff beyond stories of purpose. I think being is enough. And I can tell you from working with people who are beyond their own sense of purpose, their identity has melted away. They don't know why they're on the planet anymore. They can't answer the why questions anymore. But if I can get them to enjoy just a sensation, they're good. It's a way to hold people until they actually die. And that's been profound. I just love that stuff.

0:52:08.5 PA: It's beauty, that capacity to be moved, to be in awe, right, is...

0:52:19.3 BM: Yeah. As long as you define beauty as something bigger than pretty. Beauty is sometimes terrifying. Beauty is... I think maybe it was Justin taught me Hegel said something about, it's like, Beauty is truth embodied, essentially. So anything truly itself, whether it's a turd or a Mona Lisa or whatever it is, there's... That is beautiful. So depending on how you define beauty, yes, it's about beauty.

0:52:49.6 PA: Well, there's... And I think a misconception of aesthetic is that it's superficial.

0:52:54.5 BM: Right. Exactly. Exactly.

0:52:55.9 PA: And so when we talk about aesthetic, when we talk about beauty, inherently, there's a depth that encapsulates both the sort of inspiring and the terrifying. Huxley would talk about heaven and hell. And so we have both awesome and we have awful. And they're both awe, awe is central to those, but they're kinda two sides of the same coin, in some ways.

0:53:28.4 BM: Exactly. Excuse me. Right on. And one of the... Following what you were just saying there, I think this is... Our conventions really hurt us sometimes. I think we tend to think of wonder and terror as opposites, awful and awesome as opposites, opposed, life and death, opposed. The truth is, those are right next to each other. Beauty and terror, all that stuff is right... Those are millimeters away, if there's any separation between them at all. And that... Closing that circle that we undid and try to force into a line, reacquainting that... Those ends into the circle that they are is something that psychedelics can do, something that beauty does, and it seems to me that's very much the point. And because you do that, then you've connected life and death, then you're not at odds with reality. Then you can be sad, but you're okay being sad.

0:54:35.9 PA: There's an acceptance of what is.

0:54:38.7 BM: Yeah.

0:54:39.0 PA: Right?

0:54:39.3 BM: Yeah. Even a delighting in it, even a rolling around with it. And I got clear on that when I was in the hospital. I had horrible pain that I can barely remember. But there were moments where I was just so glad to feel anything, including pain. And that's great. I'm really... So that... If you let... If you follow these threads, if you let these things blow you open, well, then what can fall away from your experiences, all these conditions. I'll like myself if I X, Y, or Z. I'll like life if I blah, blah, blah, if it does this or that. No. Drop those conditions, if you can. If you can honestly get to a place where those conditions lose their potency, then you're really okay 'cause then you can love life without condition.

0:55:33.1 PA: And many would say this is sort of the pinnacle of development, or this is the pinnacle of experiential, or this is enlightenment, or this is... There's a lot of different ways that we've attempted to describe it, where it's precisely what you're saying, it's that it's that experience of being that often can't even be encapsulated by words. It is simply a feeling, and it's a feeling of beauty, of transcendence, of awe, of inspiration, of love, of terror, of sadness, of grief, of anger. It encapsulates a totality. And the totality is life.

0:56:11.6 BM: It's all of the above. And nothing is left out of that equation. The strength of any system I could ever imagine. I wonder if this is a law written somewhere. The strength of any model or the strength of any system is judged by how little is left out of it. So as you were just describing, nothing's left out of that equation. Nothing's isolated. You're not at odds with anything. So, yeah. Amen. Give me that.

0:56:37.1 PA: Amen. Last... We're nearing the end. We still have 10 minutes left, 10, 15 minutes left. And so there's a couple questions that I'd like to ask you that relate to regrets. That's the first one in terms of... There's a... Over the past few years, I've seen... I don't know if it's a meme or an article, like, These are the top five regrets of those who are dying. And I'd love just to hear kinda your lens and your perspective on regret. And as someone who has spent a lot of time with people who are nearing death, what are some of those... What are some of the most salient regrets that people have as they're nearing the end of their life and their existence?

0:57:24.0 BM: Yeah, so regret, that's a big one. It's a juicy subject. I've come to see regret as like a fear of the past in a sense, something like that. And some harsh relationship to what's already... Something that's already happened or didn't happen, but somehow it's linked to the past. And when you're at the end-of-life, there's not much future, sense of future then your whole life is past. And so those regrets get really poignant if you have this, if that's your relationship with the past. 'Cause that's in a sense all you have left. And so regrets is part of this condensing and concentrating experience that happens towards the end-of-life, you really get loud and really stand out. So couple thoughts... I mean, one is just like we're saying about every time I try to find something wrong that I want to change in the equation, whether it's a patient's death, like if we could just get his pain down, or if only that person didn't have regrets. Well, like we said at the beginning of the conversation, Paul, start with whatever you're feeling is all right. Fear, whatever, just start there. Just start there. So if... And I think an honest...

0:58:55.5 BM: Of course, I have regrets, and if I take regrets to mean things I wish I had done differently, of course, I do. Like fear, of course, I have fear. And I think the idea here is not... And what I see practically speaking with folks in the end-of-life is not to somehow convince them that they don't have regrets or they're not afraid, or there's no need for fear, no need for regret. It's more to say, "Oh, yeah, those are... That's normal, natural, normal." So really the one thing that I... So far, if I'm trying to change anything versus to find a way to be okay with everything, you can try to change the shame that comes with some of these states. Shame to be afraid, I'm shamed to be regretful.

0:59:42.9 BM: But by my own metric, I should probably find a reason or a way to embrace shame, too, but back to the this point about regret, so it's freaking normal. It's just yeah, okay, but it also forces you to realize, if you let it, if you follow through... Again, that's the past. You can't go back. If we somehow figured out a way to go back, I wonder if I would take that. I wonder how interested I'd be in it, but I'm glad that we can't go back because we're innocent. In a way, we're innocent before our past. It's in the past. Would I do it differently? Sure, maybe. So there... It's another knot that comes up a lot that if you go into it with people, you can open it up and there's a lot of stuff hanging out in there. And there's a lot of resolution that can happen by opening that up and talking out and letting people exorcise that regret in a sense. And that can help soften it a little bit. So it's not like everything. Something to work with, it's a vagary of us humans having this weird mind that can go backward and forward in time. But I'll also say...

1:01:00.9 PA: The curse of sentient intelligence that we were chatting about before?

1:01:07.1 BM: Yes, exactly. Yeah, part of that curse. So yeah and I think a couple of more thoughts, one is you're asking, What kind of regrets come up. Well, first, I wanna say something before I forget. Regret, I have... I see a lot of people struck by regret as they near the end-of-life, but I also see when folks are really... And it's not that someday, but the day of or really close, where they've had to let go of so many of their constructs and their thoughts, just the dead end, cul-de-sacs of their mind just had to just... They fall away by force. And I think we can choose to let go some of these things, but when you're really, really at the end, some of things by force have just been, in a sense, just driven out of you. You've had to yield again, submit again, and again. You're on your knees you just let go them because it's going you have to let go of it. There's not much of a choice.

1:02:12.8 BM: So oftentimes, regret, fear, a lot of these things, you realize, those are stuff, those are loops of a neurotic of a mind who's, that's a living that's an issue for living people, an issue for people who have still some sense of time in front of them. So a lot of the stuff will magically just melt away in the hours and moments before we die, if we let them. We, people around them might keep those stories of regret alive or fear alive. We, living people may project them onto the person who's closer to death, but really, if you let it, that stuff will melt away. So I want say that because I think a lot of our fears around death have to do with these scary things that once you're actually dying, become immaterial.

1:02:56.9 BM: So let that be a relief, but still for those of us who have some indefinite time span in front of us, we still we should work with these things. Now, finally to your question, what kind of regrets come up? Well, there is sort classic things like, no one ever regrets not spending another day in the office or something like that. In other words, don't work so hard, or something like that. Well, I've actually never heard anyone say that, and really, I think the regret... And I've also never heard anyone saying what I'm about to say to you per se, but as I translate, what I'm seeing and what I see, the big one is that they acted, they didn't, they acted from fear, not from love. And again, I'm not trying to say... Again, we all have fear, but it's when you act from that, if that becomes your sculpting tool in life, you will talk to yourself out of trying things.

1:04:09.8 BM: So if we all... If death is a failure, fine let's just work with that. If we're all gonna fail in other words, then in a way, no harm in trying. If I succeed, I fail. If I fail, I fail. Okay, whatever. Great, takes some of the sting out of it. Let death do that. But so that's what happens when someone doesn't let death into their consciousness and the existence of their conscience. They, sorry, I don't mean to conflate consciousness and conscience, two very different things, but that is the idea of isolating yourself from parts of yourself, not having a holistic view of your own self in the world and of life in the world that includes fear, death, regret other things, then you become prisoner of those things. And so back to this question, I'm finally getting to answer is the big one that I see one way or another, never really articulated this way, is that they regret that they didn't love more, or that they acted instead of, that they acted from the fear more than love.

1:05:22.5 BM: Folks who have chosen love and early enough in life to experience how painful and harsh love can be too, and that you had enough give and take. It's not just a pleasant feeling, but those of us who have chosen to love less, because it'll hurt less, once you've made peace with pain as part of the deal, well then you're not fleeing pain. So you're not avoiding pain and you're not making decisions out of some sense of safety that will keep pain at bay. You'll act from love. It's a more of an abandoned state, and those folks have a lot less to regret at the end-of-life in my experience. So, I don't know, did I finally answer your question, Paul?

1:06:02.1 PA: I think it's a beautiful cherry on the 'death sundae' that we had a chance to explore today. 'Cause it also, it goes, just to bring this back to because the podcast is somewhat psychedelic-focused. It's so cliche, of course that love is all there is, as The Beatles would say. And yet one of the biggest lessons in teaching from working with psychedelics for both myself and I know many, many, many, many others is that love is everything. And that the capacity to love ourselves, to love our family, to love our community, to love the earth and nature it creates this expansive... It creates expansion. It creates the capacity to live in a more voluptuous way. And fear while is necessary, it kind of has this contraction component. And I think my sense is a lot of people kind of on the same level, they regret not really listening to their intuition, not really listening to what it is that they knew their purpose or their mission was. Whether that's conditioning or whether that's how they were raised, or whether that's culture, whatever it is. And love transcends all of that and the experience of love transcends all of that. And it is the most important, I think, emotion or experience is love 'cause it can heal so much, so much.

1:07:49.1 BM: Amen. And I would say back to... let's make sure to not fall into the more cliche piece of it. It's like we're saying about beauty. Beauty is not like pretty, it's not necessarily pleasant. Love is not like, oh, easy, easy-peasy, I just love everything. No, no. The big love, real love is all encompassing. Love is about the least condition state we can imagine. I'll love you Paul, if you do this for me. Is that love anymore. I don't know. I don't really think so. So the love you and I are talking about here, I... What doesn't it include? And therefore, that's why it's so powerful. It doesn't kick anything out of its view. It doesn't need to... It doesn't... It takes it all in. It's the most efficient circulator of life out there because it leaves nothing out. Big love, true love. And that's love, I think you and I are talking about.

1:08:53.1 PA: A word I wrote down is devotion. That love that's unconditional. There's a devotion to a partner or a child or a business or a mission in the world. And that devotion, whether it's incredibly fun or whether it sucks sometimes. That decision, that choice to continue to show up and be devoted is I think where a lot of is... That to me sort of encapsulates love and what it means.

1:09:24.0 BM: I'm with you.

1:09:26.2 PA: Beautiful. Well, final sort of concluding question to cap all of this and somewhat of a more personal question for you is, on the topic of life and living, you've had an illustrious career of in many ways of, in the palliative care space as a medical doctor, you've written a book, you've had a Ted talk, you've done some incredible thought leadership and just caring for humans. And I'm just curious what are you excited about? What is it that you're working on? What is it that is sort of really bringing you alive, creating vitality in your existence? We're recording this December 1st, 2022, like 2023 is around the corner. What are you jazzed about? What are you really looking forward to? What's there for you BJ.

1:10:20.8 BM: Well, one answer to that question, that wonderful, generous question is, more opportunity to realize what you and I have been trying to find words for. Still more time to actually realize what we're talking about here and to feel everything we're talking about here. So that's one answer to your question. More specifically is I love what I'm up to work-wise is, a couple years ago my business partner Sonya Dolan and I started what we call Mettle Health. Mettle, M-E-T-T-L-E, mettle, like one's inner strength, one's inner reserve. And we love this little company of ours and we have been tinkering with it for two years now. Not... Wanted to kind of get it right before we try to announce it much to the world.

1:11:19.3 BM: But I think we're about at a point where the... We're ready to kind of hit the gas on developing this thing and we pulled it outside of the medical model. And it allows for us who work within this model to be much more expansive, to not be so partitioned as personal or professional to find this interplay between all the things we're talking about. In a sense a constructed thing and an invention. A vehicle for us to try to realize what we've been talking about. So that is... So building Mettle Health is what I'm really, really excited about and that's what's gonna get all my attention here coming up and making it, not just building Mettle Health as a successful company, whatever that means, but actually success would be, does it do what you and I have been laying down today and I think it has a chance to do so.

1:12:16.9 PA: And mettlehealth.com is there some information there?

1:12:20.2 BM: Yeah.

1:12:20.2 PA: Then people can kinda check out what it's about.

1:12:24.7 BM: Yeah. We got it. And we have a little, I guess we're on Instagram @mettle_health. I think it is, but, yeah.

1:12:32.5 PA: And if folks wanna learn more about your work, the title, remind us of the title of your Ted Talk. That was?

1:12:39.2 BM: Oh, well then that's funny. I named it Not Whether, But How, Ted Apparatus changed it to what matters, what really matters at the end-of-life or something like that. What matters at the end-of-life or what really matters at the end-of-life. But that's what it's officially titled.

1:12:58.5 PA: And then your book, remind us of your book name that you wrote in.

1:13:01.6 BM: That one, my co-author was Shoshana Berger, and we wrote that it's called A Beginner's Guide to the End.

1:13:10.1 PA: Oh.

1:13:11.1 BM: There's a subtitle, Practical Advice for Living Life and Facing Death or something like that. But the title is A Beginner's Guide to the End. It is, we touch on the things we're talking about today.

1:13:22.3 PA: Yeah.

1:13:22.9 BM: But it's much more of a practical guidebook to kinda move you through the paces of healthcare and advance planning and all that stuff. So, yeah.

1:13:32.7 PA: Well, we'll link to that as well.

1:13:34.9 BM: Thank you.

1:13:34.9 PA: BJ, I appreciate you spending time on this Thursday afternoon, and talking about the range of everything to have this conversation about death is, and to be with someone like you who has spent so much, you spent so much of your vitality and energy exploring this and being with this and, honoring this. And, I'm just so grateful that for your willingness to share a little piece of you and, your perspective and your wisdom with us in the podcast today.

1:14:14.3 BM: No, it's a pleasure. I'm so glad you're having these conversations and putting them out in the world. This is where it's at as far as I'm concerned, and I really appreciate you taking the time, too. Today is the anniversary of my sister's death. It's a big day for me and my family, so I'm extra glad to be talking with you about it. And, yeah. I love you, Paul. It's been a pleasure. Nice to meet you. And I love you.

1:14:36.8 PA: I love you too. BJ, this has been so fun.

[laughter]

1:14:39.9 PA: This has been so fun.

[music]

1:15:03.4 PA: This conversation is bigger than you or me, so please leave a review or comment so others can find the podcast. This small action matters more than you know. You can find show notes and transcripts to this podcast on our blog at the thirdwave.co/blog. To get weekly updates from the leading edge of the psychedelic renaissance, you can sign up for our newsletter Frequency at the thirdwave.co/newsletter, and you can also find us on Instagram at @thirdwaveishere, or subscribe to our YouTube channel at YouTube.com/thethirdwave.