“We have to be careful not to pigeonhole psychedelics as something specific, like an antidepressant. That’s the wrong framing. They are broader tools for connecting us to the wholeness of the natural world. When our global society embraces their value, psychedelics can help save us from disaster.”

– Roland Kupers, author of A Climate Policy Revolution.

How did a former corporate executive with no prior psychedelic experience conclude that a psychedelic revolution is foundational to climate change? Simple, he did his homework.

In his book, A Climate Policy Revolution, Kupers argues that the planet is nearly past the point of salvation, and nothing short of rapid systemic change can steer this ship around. For monumental change to occur, people have to care first. They have to feel in sync with the natural world; and that anything short of its infinite survival is unacceptable. To feel that connection, Kupers argues people may just need a dose of psychedelic therapy.

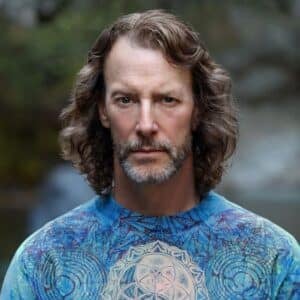

Roland Kupers: A Man Driven to Solve

Before changing paths, Roland Kupers spent 23 years in the corporate sector, where he ultimately served as Shell’s head of sustainable development. Throughout his tenure at Shell, Roland spent countless hours tackling complex issues such as preserving whale populations in Siberia. But life was too short to stay confined to the business world.

So ten years ago, Kupers walked away from Shell to write, teach and advise on how to think about complex systems and implement practical solutions to unimaginable challenges. Among his latest lofty tasks: solving climate change.

But wait–what are systems?

A system is a set of things that work together and rely on each other to make up the whole.

“In school, you learn to solve a systems problem by fixing its broken pieces. That makes a lot of sense when you’re dealing with mechanistic systems like a refrigerator. But it doesn’t make much sense when you’re dealing with society, where the whole is bigger than the parts,” said Kupers.

According to Kupers, society is much like a complex ecological system whose parts rely on each other for the survival of the whole.

“If you take out a certain animal or plant species, that will damage the balance of the whole ecological system because these species interact and are interdependent. And that interdependency is more important than one particular species’ survival. So our ecosystem is not just the people, or the birds, or the trees that inhabit it. It’s a holistic living structure that we collectively create.”

To solve climate change, then, people have to go beyond fixing individual parts of the system. It’s not enough to replace fossil fuels with green energy and electric cars. These solutions solve only small sections of the puzzle without putting the entire thing together.

“The reality is we can’t make individual changes quickly enough to reverse the damage,” said Kupers.

To solve climate change, Kupers argues people have to understand the interconnectedness of our world. And they have to care. “Or else we’re literally toast,” he said. “If people’s attitudes are, ‘what has nature ever done for me, and why does it need me now?’ this is never going to work.”

If only there were a magical solution.

The Fundamental Role of Psychedelics

Fortunately, Kupers believes systems can change quickly under the right circumstances. That’s why he set out on a science-driven mission to figure how to make people care. In the process, he stumbled upon an Imperial College research paper published just a few years ago.

In the paper, the Psychedelic Research Group at Imperial College analyzed a large sample size to determine whether people’s affinity for nature changed after just one psilocybin trip. To no one’s surprise (who’s ever experienced magic mushrooms), the difference was statistically measurable. More significantly, the feelings of interconnectedness lasted months after the treatment.

Kupers also read Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind. Already a fan of Pollan’s earlier work, Kupers trusted his perspectives and connected to his approachable writing style.

“Michael Pollan has done such an incredible job of responsibly popularizing psychedelics and bringing his world of experience to mainstream society,” said Kupers.

Like Pollan, Kupers believes there’s no substitute for personal experience, so he quickly planned his first psychedelic journey. Accompanied by a knowledgeable guide, Kupers visited his friend’s country house one “beautiful autumn day,” took magic mushrooms, and wandered through the forest to confirm Imperial College’s conclusions first-hand.

“The argument I now make is that we have these substances that aren’t addictive (as opposed to legal drugs like opioids), and they perform an essential function for climate policy because they make us aware of the wholeness of the natural world. And I don’t just mean individual pieces of nature, like the trees. Psychedelics create an understanding of the entire ecosystem, including everything and every person in it. Therefore, it’s doubly crazy that our lawmakers suppress and criminalize the use of psychedelics,” said Kupers.

A Return to What We Already Know

Indigenous peoples have been working with psychedelic drugs, including psilocybin, ayahuasca, and peyote for centuries. Through ceremonial and social use, they’ve developed traditions based on interconnectedness, healing, and spirituality. It’s no surprise that these traditions are also rooted in nature.

In the 20th century, Western society caught on to these transformative substances, and respected researchers championed their use. Psychedelic chemist Alexander Shulgin, for example, was a top-ranked researcher for Dow Chemicals until he ingested mescaline in 1960. Six years later, he left Dow and went on to synthesize more than 200 psychotropic compounds. Timothy Leary, an elite clinical psychiatry professional, conducted several Harvard-funded experiments in the ’60s to understand psychotropic effects on the mind. Leary was also one of the leading figures in the psychedelic counterculture movement.

Driven in part by psychedelic epiphanies, hippies of the 60s subculture movement infamously made grand gestures of peace and love towards everything and everyone–except the establishment.

“Political leaders during that time said they were banning these substances because they were medically dangerous. But that was never the real reason. Psychedelics threatened the order of things, and leaders wanted to solidify their power. But the situation is different today. The established order recognizes that we’re in a dead-end street, so there may be room for legalization,” said Kupers.

But to preserve the planet, Kupers argues that proponents can’t focus solely on psychedelic medicine for mental health issues like addiction, treatment-resistant depression, and anxiety. Today’s psychedelic revolution cannot narrowly focus on countering false narratives of the past with new medical research. Instead, it must focus on how these substances can save the world.

“We need to reframe psychedelics in a way that gets us closer to the 1960’s ideal that they’re a tool for transforming the way we think about society and nature. So what I hope to do with this book is to help frame psychedelics outside the functional medical realm, as a useful way to solidify our rapport with nature.”

But first, psychedelics need to be part of mainstream policy.

How to Change Global Drug Policy

According to Kupers, society is already on its way to changing drug policies by bringing psychedelic research and experiences to the forefront of mainstream conversations. Clinical trials like MAPS’ LSD-assisted psychotherapy research, books like Michael Pollan’s How to Change Your Mind, and articles like The Economist’s recent piece on decriminalization are all integral to the modern psychedelic revolution. And these are just a few examples.

In 2010, Kupers was particularly struck by an article published in The Lancet, the UK’s premier medical research journal. The paper compared 20 of the most common drugs in terms of individual and societal damage. After analyzing the impact of these drugs based on 16 criteria, the results showed that alcohol was the most harmful overall, by far. Heroin and crack rolled in at second and third places. Cannabis curiously arrived in eighth place, and MDMA, LSD, and mushrooms appeared in the last few spots, respectively.

“You couldn’t be more mainstream than the Lancet. And its research shows no reason to ban psychedelics. So people don’t need a justification to legalize these substances; they’re as safe as other things we don’t outlaw,” said Kupers.

How to Convince the Masses

“I’m not saying we put psychedelics in the drinking water… but almost,” joked Kupers.

To promote widespread use, Kupers thinks politicians and government organizations must formally make psychedelics part of global policy change recommendations.

“You have platforms like the Glasgow Climate Change Conference (UNFCCC) every year and events like President Biden’s Climate Summit. These are the places where leaders need to incorporate psychedelics into the conversation–both verbally and in written form,” said Kupers.

Kupers thinks politicians should add “experiencing nature through psychedelics” to their long list of climate policy measures, which already includes reducing red meat consumption and traveling by plane less. If respected leaders and organizations pushed the agenda, they could convince the masses who may be intrigued, slightly hesitant, or even resistant to the idea.

“Of course, it’s always important to refer back to the scientific bases for the argument, such as the research from the Imperial College study,” said Kupers.

Why the Psychedelic Revolution will Succeed

“I think change can happen much faster than anyone thinks. Just look at the psychedelic revolution shift in just the last few years. The narratives today are powerful. The hardest nut to crack will be the underlying social reasons these substances were banned in the first place.”

But Kupers points to examples all around the world that give him hope.

“Look at gay marriage in the US. Or even the psychedelics market in the Netherlands. Psychedelics aren’t technically legal in the Netherlands, but authorities decided drugs were not a criminal problem and have allowed the industry to flourish.”

People worldwide are already discussing psychedelics and thinking about their value, especially their medical use. In the US, states like Colorado, New York, and Oregon have either implemented or talked about passing decriminalization measures. Now it’s time for proponents to add psychedelics’ climate change connection to the conversation. An uphill yet worthwhile battle, indeed.

Disclosure: This article contains offers and affiliate links. Third Wave receives a small percentage of the product price if you purchase through affiliate links. Read our ethics and affiliates policy here.